O que diria Walter Benjamin se reaparecesse por aqui? Como reagiria frente à arte e sua reprodutibilidade depois, sobretudo, da internet e dos smartphones? Reveria sua crença na perda da aura da obra de arte diante da suposta desartização das obras produzidas com os meios tecnológicos? E quanto ao valor de culto da arte tradicional, Benjamin confirmaria que ele foi, de fato, suplantado pelo valor de exibição?

Entusiasta da propagação da arte pelos meios de reprodução, Benjamin via a fotografia e o cinema como fundamentais para a democratização da obra de arte. Reproduzida ou produzida por esses meios, ela seria finalmente despojada do prestígio ligado à sua suposta origem religiosa, possibilitando, assim, uma outra relação com o homem comum. Nesta nova situação, todos passariam a ser vistos não mais apenas como receptores, mas também como produtores possíveis.

Passadas décadas da publicação do ensaio de Benjamin, “A obra de arte na era de sua reprodutibilidade técnica”, filas e filas se formam para ver de perto a Mona Lisa, de da Vinci, no Louvre (cuja imagem foi e é reproduzida inúmeras vezes) – para ficarmos apenas com um único exemplo ligado às artes visuais. Hoje filmes os mais diversos são “cult”. “Cult” é também o título de uma revista dedicada ao culto da cultura e de uma plataforma do Telecine on demand; “cult” é a cantora trans, como também “aquela” fotografia “daquele” fotógrafo.

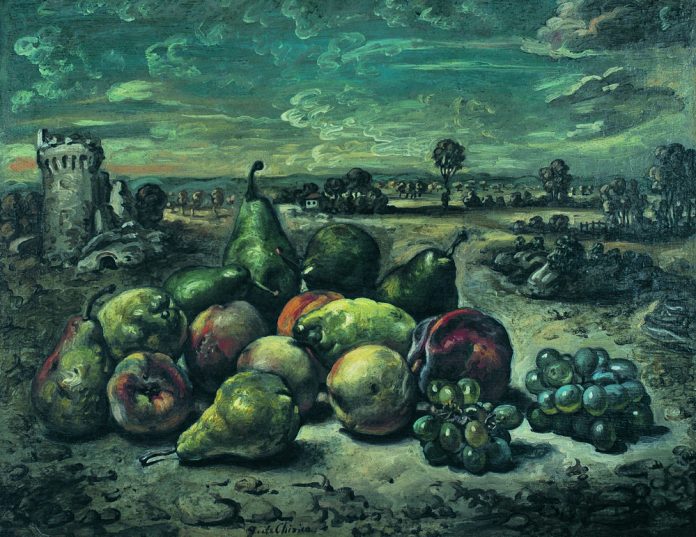

Segundo Benjamin, a obra de arte tradicional trazia com ela o valor de culto por causa da aura que dela emanava: ela era única, preciosa mas, na medida em que perdeu essas qualidades, devido aos processos de reprodução, passou a ser igual a todos os tipos de objetos, restando-lhe apenas o seu valor de exibição, ou seja, sua capacidade de estar em todos os lugares.

Qualquer fotografia, portanto, teria como base o seu valor de exibição suplantando qualquer possibilidade de possuir ou vir a possuir algum valor de culto. Afinal em sua própria condição de existência, reina sua capacidade de se reproduzir indefinidamente, certo? Não, errado. Não há dúvidas de que as câmeras digitais acopladas a celulares estão levando a proliferação da fotografia a patamares até então impensáveis. Entretanto, ao mesmo tempo em que os smartphones transformam seus proprietários em produtores compulsivos de fotografias que se espalham e se exibem rapidamente por todo o globo, existem fotografias que têm seu valor intrínseco de exibição restringido, sendo a ele sobreposto o antigo valor de culto.

Existe no mundo um conjunto de fotografias cujo valor de culto é criado por terem como característica o fato de serem vintage (foram reproduzidas na época de sua captação pelos próprios autores, elevados agora à condição de artistas e não de “meros” fotógrafos), ou por fazerem parte de uma produção post mortem, porém com um número limitado de exemplares. São essas relíquias sobreviventes de um tempo heroico qualquer – construído pela história e/ou pelo mercado –, que nos fazem peregrinar por museus e galerias a prestar-lhes homenagens, que fazem com que nos desloquemos para esses templos a fim de compartilharmos com poucos o nosso deleite frente àqueles fetiches quase únicos, praticamente únicos.

Os advérbios “quase” e “praticamente”, neste contexto, alertam para um fato na prática inquestionável: postar-se diante de uma fotografia produzida, por exemplo, em 1939, e que teve apenas alguns exemplares produzidos por aquele ou aquela que captou a imagem, é como estar frente a uma pintura. E isso porque, hoje em dia, um exemplar de, por exemplo, seis reproduções idênticas produzidas há 80 anos – num mundo saturado de imagens –, é capaz de fazer emanar uma autenticidade, uma aura de mistério e revelação (não é isso o que os objetos votivos provocam em quem os olha?), que nos embriaga de puro deleite, como se ele fosse único.

Se fitar essas imagens raras é um deleite, possuí-las, então, é um sonho de poder e gozo. E, por mais cara que possa ser uma fotografia vintage, ou de restrita edição, quase sempre ela é mais acessível do que “aquela” pintura ou “aquela” escultura que sobretudo o colecionador médio nunca irá possuir.

***

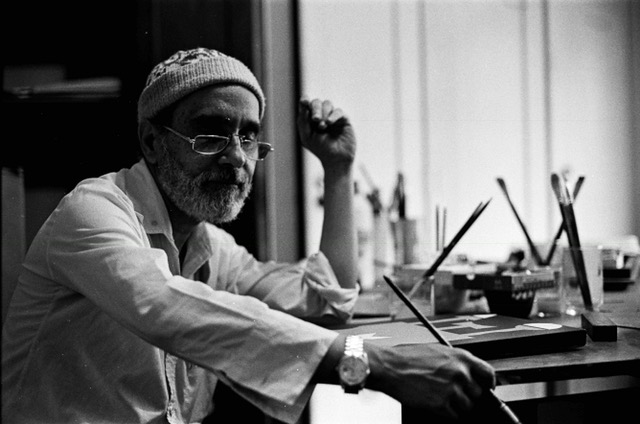

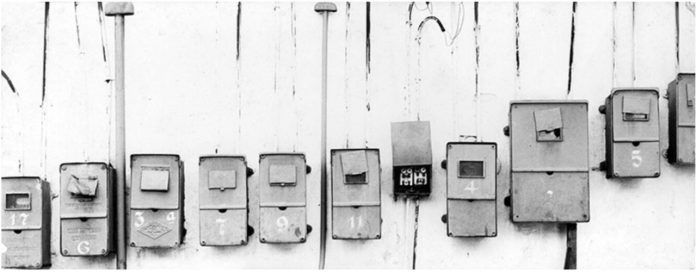

Essas questões surgiram a partir da visita à “Fotografia Moderna 1940-1960”, em cartaz na Luciana Brito Galeria, em São Paulo. A mostra possui uma particularidade: apresenta obras de alguns dos fotógrafos brasileiros modernos mais prestigiados no espaço que antes foi uma residência projetada pelo arquiteto modernista Rino Levi. Difícil melhor container para abrigar alguns vintages de Geraldo de Barros, Thomas Farkas e outros, além de obras de uma única fotógrafa, Gertrudes Altschul. O espaço concebido por Levi traz solenidade às obras, dado que renova/amplia a aura que delas emana (embora a própria aura da casa também não deixe de impregná-las).

Se a exposição se inicia com alguma tibieza, com algumas obras de Paulo Pires, dentro da cartilha do que deveria ser uma fotografia em “estilo moderno”, logo na sequência ela passa a apresentar a dimensão experimental alcançada pela fotografia do período. Se na mostra se destacam os sempre estimulantes Geraldo de Barros e Thomaz Farkas, a grata surpresa foram as fotos de Marcel Giró, um modernista cuja produção mereceria ser mais divulgada.

Se os fotógrafos presentes na mostra, cada um à sua maneira, acreditavam que a fotografia poderia ser encarada e produzida como arte ou, mais como uma das “belas artes” (em alguns casos), não resta dúvida de que conseguiram provar que tais disposições eram possíveis, quer pela obediência às normas foto-clubistas então imperantes, quer pelo rompimento das mesmas. Hoje, devidamente emolduradas e dispostas em um ambiente que as reflete e endossa, reiteram a aparente falência dos constructos teóricos de Walter Benjamin, aqui comentados, em parte solapados pelos próprios fotógrafos, pelo mercado de arte e pelo colecionismo que conseguiram transformar aquelas peças em “quase” originais – objetos de deleite e de culto.

Tanto para aqueles que não se importam com tais questões, quanto para os que as consideram fundamentais para pensar sobre o estatuto da fotografia nos dias de hoje, “Fotografia Moderna – 1940-1960” é uma exposição obrigatória.