On november 13, 2015, American photographer Peter van Agtmael was in Paris during a massive terrorist attack by ISIS. In the evening, upon returning to the hotel room, Peter felt paranoid for the first time in a long time. “I’d been covering conflict for ten years, and I’d always been able to prepare myself for the experience. This time, caught unawares, I stayed half awake the whole night”, he says. The shock continued to reverberate even after the photographer returned home to New York City. Until then, while using the subway, Peter found himself keeping his back to the wall whenever it was possible, and scanning every face, while charting his escape routes. “I’d always been a visitor to other people’s conflicts, but in Paris, when violence arrived so suddenly in a space I’d associated with comfort and sanctuary, I got a small understanding of what ordinary people living in a war feel every day. Ten years of work in conflict, and I’d missed one of the most fundamental lessons.”

Such dissonance between the Americans’ perceptions of the post-9/11 wars and the violence experienced by people trapped in conflict zones is the narrative basis of Peter’s latest project, Sorry for the War. In it, the photos sequenced in a non-linear manner interlace and sew together the war in Iraq during the time of ISIS, the mass exodus of refugees to Europe, militarism, terrorism, nationalism, myth-making and war propaganda. The material gathered in Sorry for the War (whose texts and subtitles are written in both English and Arabic) reminds us that although the recent wars of the United States have been virtually forgotten, their consequences continue to reverberate, as the author notes.

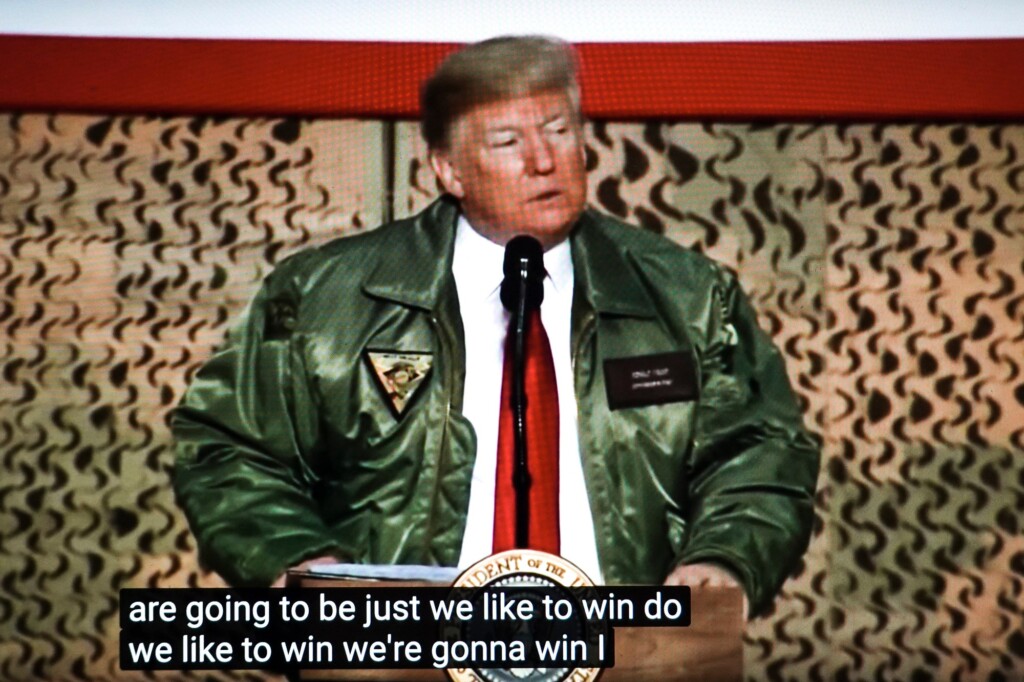

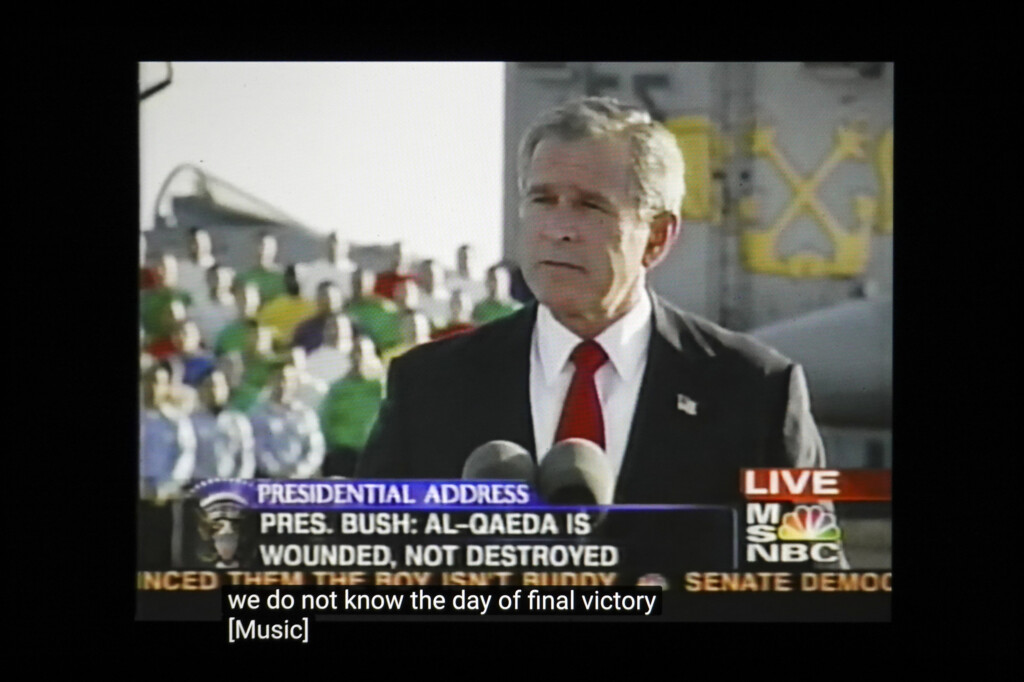

The disturbing, endowed with acid humor (accentuated by the plasticity brought in by the use of flash and the cunning ordering of images in the book), contradictory, mysterious and sometimes condemning records are articulated by Peter to study the construction of the idea of an endless war. Although it shows a post-9/11 world – “attack that ‘gave us license’ to use our fears as an excuse for anything” -, Sorry for the War fulfills the duty of using recent history as a guide, but not to be limited to it, since one should “also have to look at the totality of American history as a framework. Things don’t just happen because of one event, they happen as part of the continuum of history”. Off the front, the photographer focuses on the aftermath of this culture, “serving both as evidence and interpretation of a country gone adrift, with often disastrous consequences”, and including the notion of eternal war, exemplified very well in four records of televised speeches by the past U.S. presidents (Bush Senior and Junior, Obama and Trump; with the exception of Bill Clinton), whose addresses should announce the end of certain conflicts and end up reinforcing, in these frozen excerpts by Peter, the other way.

The title of the book, found in a pink post-it on the cover of the publication, comes from a photograph taken by Peter of an action, with the name Balloons for Kabul, at an art gallery in New York. “New Yorkers wrote notes to the people of Kabul that would be handed out to them with pink balloons during their morning commute. It was a well-intended but totally out of touch response to a then already decade-long conflict. Much of the work that I do is about the disconnect between the us and the consequences of its — or of our — imperial actions abroad. That note, and that event, seemed to symbolize a lot of my mistrust and cynicism I had for our distorted idea of collective empathy.”, he tells, the also photographer, Tanya Habjouqa. “That note seemed appropriate because this book is my apology, and a statement of helplessness, about what has happened these past two decades. I can’t change any outcome, but I can certainly create a rigorous document interpreting what’s come to pass. And I think that’s partly why the gaze on the Americans in this book is kind of brutal and sardonic. I’ve come to know the violence at the heart of America very well. The generosity and grace as well, but just this unremitting violence.”, complements the photographer.

The choice of satire as a vehicle for criticism – rather than the deliberate use of shock – shows not only his experience (vast to such a young professional), but outlines a path contrary to that of the news market, as Susan Sontag explains in the book Regarding the Pain of Others: “The hunt for more dramatic (as they’re often described) images drives the photographic enterprise, and is part of the normality of a culture in which shock has become a leading stimulus of consumption and source of value”. Concerning the ‘shock- photos’ (as Roland Barthes called it), Sontag would question: “Can you look at this?”. “There is the satisfaction of being able to look at the image without flinching. [But also] there is the pleasure of flinching [in the face of horror]”. Whether by indignation, mystery or satire, Peter manages to maintain, throughout Sorry for the War, the prevalence of “why?”. “Why was this face in Guantanamo hidden?”; “why do people go to museums to look at drones?”; “why is the scenario behind this child in ruins?”; “why is there a huge sporting celebration in the middle of a book about conflict?”.

Visualizing war?

At a time when politics is often consumed by citizens in a visual way – through social media, video news coverage or popular culture – the need to become aware of the weight of visual communication is ever-more pressing. “This need becomes even greater when we consider that so few of us now have direct experience of war or the military”, argue Nick Robinson and Marcus Schulzke in the study Visualizing War? Towards a Visual Analysis of Videogames and Social Media. According to the authors, war – as it is increasingly experienced by its citizens remotely – ends up being presented as a spectacle centered on the usage of ever-more powerful and technologically sophisticated artillery (e.g. recent images demonstrating the power of the Iron Dome in Israel, sometimes similar to scenes from Star Wars, other times with fireworks).

Robinson and Schulzke point out that: “The consequences of this increasing portrayal of war as entertainment may suggest a move towards an increasingly soporific citizenry that becomes progressively disengaged, no longer questioning why we fight, instead, losing itself in the fact that we fight”. The researchers add that it is possible to observe a variety of citizens’ responses to this kind of content ranging from “distraction, bedazzlement and voyeurism” to “being positively mobilised to actively support military action”.

An important observation made in Visualizing War is that a considerable sample of studies on militarism “emphasize the ways in which nationalistic and militaristic themes emerge in conjunction”, in the interest of a State and its armed forces. Using the United States as a case study, Robinson and Schulzke claim that “the recent disillusionment with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, combined with a demand to ‘support the troops’ at all times, has led to a subgenre of war media that demonstrate this”. This phenomenon is also described by Peter:

Over recent years, we’ve had a president who created an atmosphere of deep fear by exploiting the idea of threats to this country, our freedom, our security. So, when I look at the presidency of Trump, I see the post- 9/11 world written all over it. The year of 2020 was, to me, the culmination of recent American history. It embodied all the political forces that have been in motion for the last few decades, where nationalism and identity politics took the forefront again.

The study also draws attention to the images of conflict created for video games and, further, their marketing. It is estimated that Call of Duty, for example, has approximately 100 million participants worldwide and that sales of premium products encompassed by the franchise have exceeded 400 million dollars since its launch in October 2003. This is not an isolated case, however. As Roger Stahl, associate professor of Communication Studies at the University of Georgia, identified: “September 11, 2001 and the ensuing wars in Afghanistan and Iraq ushered in a boom in sales of war-themed video games for the commercial market”.

Citing the work of Vit Šisler, a researcher focused on the intersection of culture and digital media and assistant professor at Charles University in Prague, the study points out that military games typically contain stereotypical depictions of Muslims. Šisler argues that “the enemy” is collectivized and linguistically identified as “various terrorist groups”, “militants”, and “insurgents”, while American or allied troops are humanized and individualized, with playable and non-playable characters “portrayed with nicknames or specific visual characteristics”. In addition, the “allied forces” are also shown as part of a multilateral force (a coalition of the willing), which would justify “the rhetoric of a war on terror with the Middle Eastern enemy seen as requiring near continuous military intervention and restraint”. But not only: taking as a starting point such representations, it is possible to assume, controversially, that complex social and political problems can be solved in a solely military way. With resistance to this visual typification, Peter van Agtmael reports to Tanya Habjouqa: “When my eye is directed towards the Iraqis, Afghans, and Syrians caught in the middle of this mess, it’s a lot more gentle. And that’s partly because I have a greater degree of sympathy for the true victims of this conflict. And partly it’s a reaction to the fact that these groups have generally been visually marginalized and only seen in moments of extreme violence and grief over the history of photography. I want to push back against those forces”.

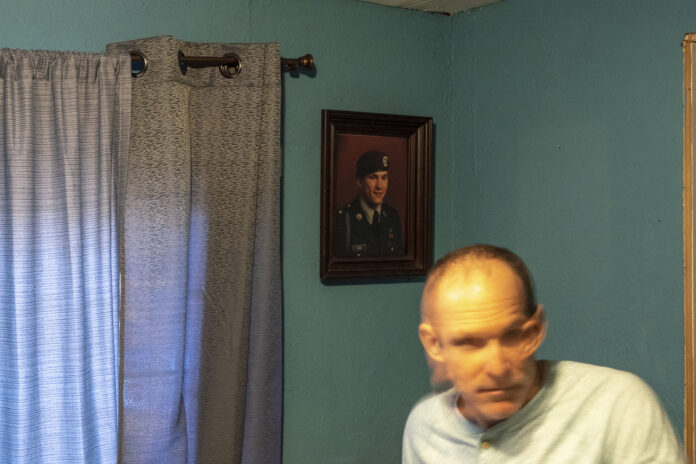

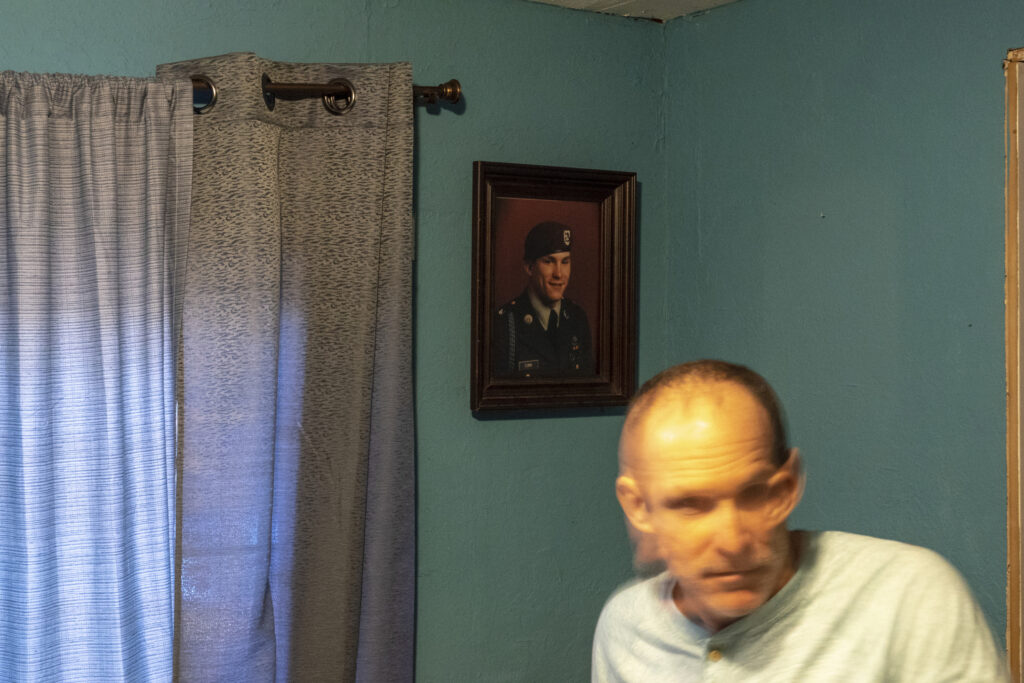

Even though, as stated at the beginning of this article, his look at the Americans is more analytical, in Sorry for the War, Peter directs his poignant criticism to the State and to imperialism, not depriving the individual soldiers from his homeland from a humanized portrayal too. Some of these characters deal with physical sequelae from their time in combat, others psychological ones, or even criminality linked to unemployment.

Meredith Kleykamp, director of the Center for Research on Military Organization at the University of Maryland, points out that unemployment rates are higher among veterans compared to non- veterans, with the largest disparity occurring among women. In the study Unemployment, earnings and enrollment among post 9/11 veterans, Kleykamp points out that in 2011, approximately 12% of all post-9/11 veterans and nearly 30% of those aged between 18 and 24 were unemployed. Given that today’s veterans are more likely, than their peers from previous generations, to marry and have children, the effects of the transition between military and civilian life present setbacks that extend to their spouses, children and communities. In previous research, she points out that not all soldiers enter military life with aspirations to grow in the army. “Youth with lower socioeconomic status backgrounds were nearly half as likely to enroll in college rather than enlist in the military as their peers from more advantaged backgrounds”, explains. The results of her analysis show that educational goals play an important role in the decision to enlist in the armed forces in the United States, even more with the “Post 9/11 GI Bill”, launched in August 2009, which pays public school in-state tuition and fees.

Army Dreamers

“Mourning in the aerodrome. The weather warmer, he is colder. Four men in uniform to carry home my little soldier,” sings Kate Bush in Army Dreamers, one of 68 songs deemed “inappropriate” to play on the BBC, the UK’s public radio and television corporation, during the Gulf War, for which the British mobilized the largest contingent of soldiers among any European state that participated in combat operations.

A little more than a decade later, the UK became involved in the Iraq War, which began in 2003 and ended in 2011, with the official closure of British combat operations on 30 April 2009.

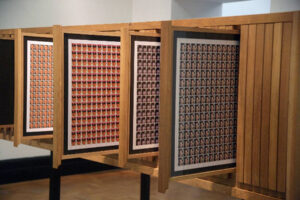

In the course of the conflict, Steve McQueen was selected by the official artists program of the Imperial War Museum to produce a work of art on the British Armed Forces. In 2006, he traveled to Basra, one of the three largest cities in Iraq, where he spent six days embedded with British troops. Having worked with video art for at least a decade at that point, McQueen planned to produce a testimonial film about troops serving in Iraq; however, even integrated with the fighters, he was subjected to movement restrictions that left him frustrated and nullified his plans. Later, at his home in Amsterdam, McQueen was posting his income tax return when he realized that the stamp on the envelope had a portrait of Vincent van Gogh. The proportions of the portrait on the stamp and the fact that they can reach the various corners of the world, made the idea sound promising to the artist. Imprinting the stamps would be the portraits of soldiers who had died in combat, as a form of tribute. McQueen declared: “An official set of Royal Mail stamps struck me as an intimate but distinguished way of highlighting the sacrifice of individuals in defence of our national ideals. The stamps would focus on individual experience without euphemism. It would form an intimate reflection of national loss that would involve the families of the dead and permeate the everyday – every household and every office”.

Faced with the lack of interest shown by the Ministry of Defense when McQueen presented his project, the artist hired a researcher to contact each one of the families of the fallen soldiers and request an image of their lost ones, as the ministry had also refused to provide the portraits. Initially, 115 families were contacted, of which 102 responded and, of these, 98 agreed to participate. Since the beginning of the project, however, casualties occurred and, likewise, all families were invited by the artist to participate in the project and honor their loved ones in Queen and Country.

For the final version of the work, McQueen created an oak cabinet containing 120 double- sided vertical panels, which can be removed for viewing, and on which 160 sheets of stamps are displayed with portraits of the British military personnel who died in service in Iraq. Each sheet contains details such as name, regiment, age and date of death printed on its margin. In the cabinet, the leaves are placed in chronological order, from the seven casualties on March 21, 2003, to raf Sergeant “Baz” Barwood, who died on February 29, 2008. For the BBC’s Jo O’Connor, Steve McQueen said he hoped the exhibition would allow people to think about the victims of the war. “Over 650,000 or more Iraqi men, women and children have also died in this conflict and I am hoping that by allowing people to identify with British soldiers who have died, they will also think about the people in Iraq”.

According to the artist, Queen and Country can never be considered complete until the Royal Mail allows the general use of the stamps. The British postal service denied McQueen’s proposal, justifying that the families of the dead and the public would find the stamps “distressing and disrespectful”, despite the solid support shown by the families, the military and also by the public, who gathered 26,673 signatures in a petition to support the project when Queen and Country finished its exhibition across the uK in 2010.

If I Could Do Anything For You

For art curator Moacir dos Anjos, in Introduction to Aesthetics: A Conversation between Art, Philosophy and Psychoanalysis, the works of Steve McQueen and Emily Jacir suffer a cross-pollinatation when they refer to mourning and the brutal consequences of conflicts; in particular, Moacir cites the photographic installation Where We Come From, by the Palestinian Jacir.

In July 1950, the Law of Return was adopted by the Knesset in Israel, according to which every Jew – regardless of their origin in the world – could claim the right to citizenship and residence in the State of Israel. In contrast, more than 700,000 Palestinians were expelled or fled the region during its foundation. Exiled by the exiles. Peter Beinart, in an opinion piece for The New York Times, suggests that “acknowledging and beginning to remedy that expulsion — by allowing Palestinian refugees to return — requires imagining a different kind of country, where Palestinians are considered equal citizens, not a demographic threat. To avoid this reckoning, the Israeli government and its American Jewish allies insist that Palestinian refugees abandon hope of returning to their homeland”.

For Edward Said, whose text Orientalism is considered one of the founders of post-colonialist thought, “It is as if the reconstructed Jewish collective experience, as represented by Israel and modern Zionism, could not tolerate another story of dispossession and loss to exist alongside it—an intolerance constantly reinforced by the Israeli hostility to the nationalism of the Palestinians, who for have been painfully reassembling a national identity in exile”.

In this context, taking advantage of her ability to move with relative freedom in Israel with an American passport, Emily Jacir proposed the following question to other Palestinians: “If I could do anything for you, anywhere in Palestine, what would it be?”. In a non-material exchange, they provide their desires, longings and dreams, and she promises to realize them. “She makes her body an extension of these people’s bodies to fulfill their desires,” as Moacir dos Anjos puts it.

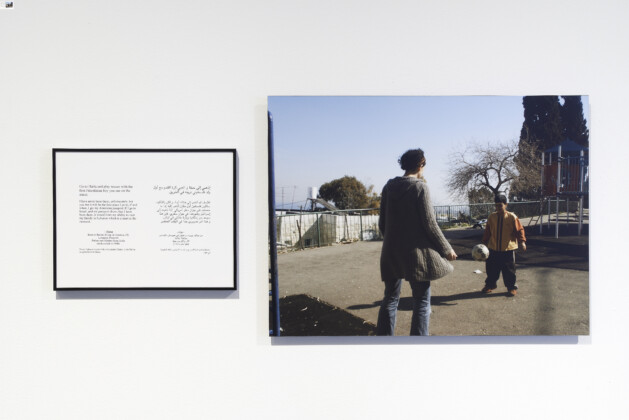

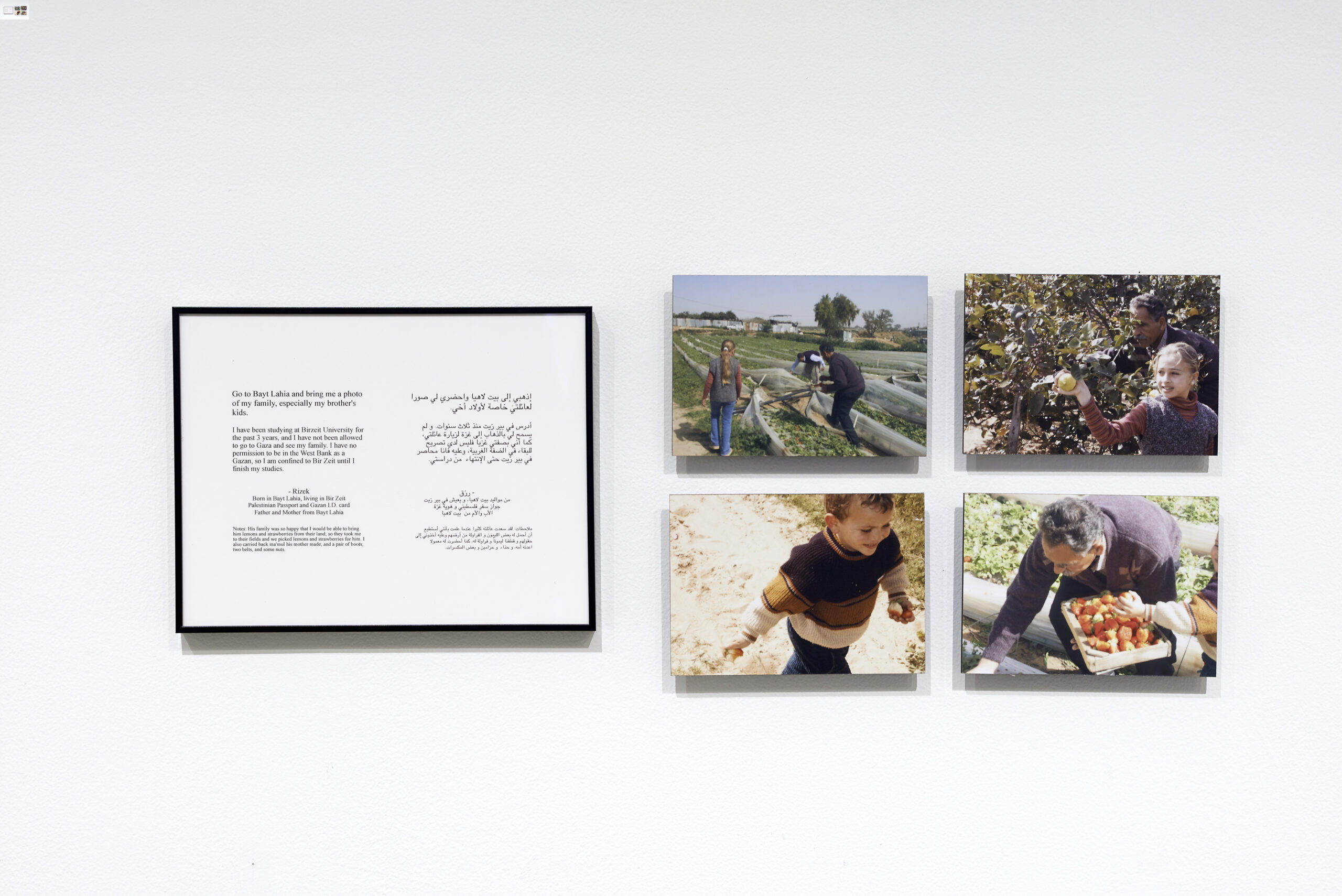

In the presentation of Where We Come From, against white panels, black letters describe requests made to Jacir (transcribed in English and Arabic) and immediately by its side, the artist inserts color photos as a documentary update of her mission. In some cases, such as Rizek’s, she adds her own notes below the request. “Go to Bayt Lahia and bring me a picture of my family, especially my brother’s kids. I have been studying at Birzeit University for the past three years, and I have not been allowed to go to Gaza and see my family. I have no permission to be in the West Bank, as a Gazan, so I am confined to Bir Zeit until I finish my studies”, asked Rizek. In her note, Jacir reports that “his family was so happy that I would be able to bring him lemons and strawberries from their land; so they took me to their fields and we picked lemons and strawberries for him. I also carried back ma’mul his mother made, and a pair of boots, two belts and some nuts”. Four photographs show Rizek’s family, and his brother’s children, picking the strawberries and lemons that Jacir cites.

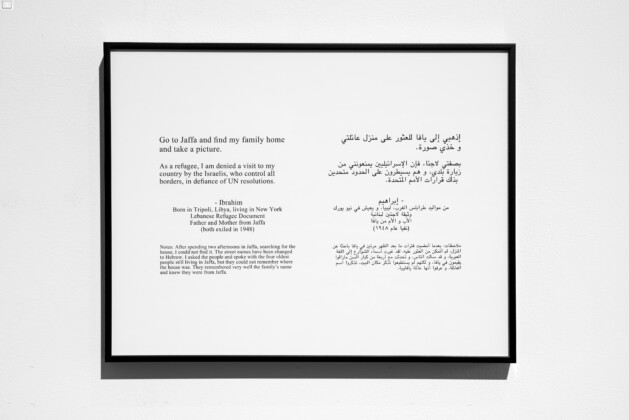

Descriptions involve things we usually take for granted, as guaranteed: visiting our family, playing football, seeing our childhood home. The latter being the case of Ibrahim. “Go to Jaffa and find my family home and take a picture. As a refugee, I am denied a visit to my country by the Israelis, who control all borders, in defiance of un resolutions”. When weaving her answer, the artist admits her failure to get what she had promised in return: “After spending two afternoons in Jaffa, searching for the house, I could not find it. The street names have been changed to Hebrew. I asked the people and spoke with the four oldest people still living in Jaffa, but they could not remember where the house was. They remembered very well the family’s name and knew they were from Jaffa.” In this piece, the part intended for the photographic record is blank.

“Yet it is just this translation, written out in clear language and then realized photographically, that for many is insurmountable. Getting from written description to photographic actualization can be easy enough for some, like Jacir, who have American passports. But for other unfortunates caught up in the politics of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that has been raging since 1948, when so many were exiled from their land, the terrain between text and photograph, description and realization, represents an unbridgeable chasm, an impossibility on which a complex of desire is built.”, writes the historian and cultural critic TJ Demos in an essay on the work. “These pieces stage a perverse inequality between things and people. That inequality is the ability of commodities to move about relatively freely through global markets and across national borders, whereas people are restricted physically and geographically. People, not things, are denied entry into certain territories or nations, regimented in ways that are politically instrumental to maintaining political bodies, economic groupings, and ethnic identities.”, adds Demos.

Where We Come From was carried out from 2001 to 2003, Moacir recalls that, the following year, Jacir issued a note clarifying that she would no longer be able to carry out the project, “I am no longer allowed to enter Gaza, and certain Palestinian towns in the West Bank. Israel is relentlessly moving forward in the construction of the Apartheid Wall which began in the spring of 2002. Palestinians with foreign passports are increasingly being denied entry into the country by Israel at all border crossings and are being forced to immigrate. Israel has decided that ‘freedom of movement’ is no longer a right for American passport holders and has created measures to ensure this”, writes the artist in the note.

Even if they alternate between different media and fields – from installation to documentary photography – the four works referred to in this article share the fact that they are documents of suffering, and as written by Susie Linfield: “Documents of suffering are documents of protest: they show us what happens when we unmake the world”.

…

Leia em português, clique aqui.