Mais do que estudar a hegemonia que as vertentes construtivas – os movimentos concreto e neoconcreto – alcançaram no âmbito da crítica e da história da arte locais, me interessa aqui arrolar alguns diálogos que certos artistas com elas propuseram travar, relativizando seus pressupostos. Trazer à tona esses desvios às “normas” concreta e neoconcreta instituídas é, a meu ver, contribuir para o debate sobre a arte no país, questionando interpretações cristalizadas.

Se o neoconcretismo deve ser entendido como uma dissidência do concretismo, ele, com certeza, não foi o único que abrigou estratégias para desconstruir os postulados daquele movimento. Por outro lado, seu caráter alternativo em relação ao concretismo não o livrou de tornar-se igualmente objeto de crítica de artistas que duvidaram da eficácia supostamente libertária de alguma de suas proposições, assim como de sua rápida ascensão à condição de “a” manifestação artística brasileira e contemporânea.

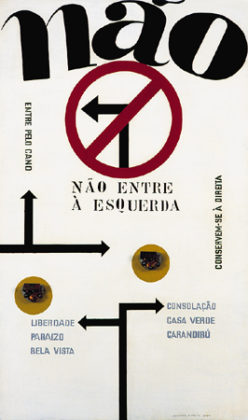

Se a expressão Popcreto foi pensada por Augusto de Campos para definir o processo de “semantização” pelo qual passava a produção de Waldemar Cordeiro – após o artista ter superado as limitações do concretismo que ele mesmo lutara para fazer imperar –, o mesmo termo pode ser usado para definir pelo menos parte da produção de outros artistas atuantes em São Paulo no início dos anos 1960. Lembro aqui de Maurício Nogueira Lima, também de passado concretista: sua obra Não entre à esquerda (1964), estruturada a partir da grade modernista tão prezada pelos concretos, surgia contaminada pelo embate político-ideológico então travado no país, colocando em xeque os postulados idealizantes do concretismo.

Muitas obras produzidas por Nelson Leirner naquela mesma década também poderiam ser pensadas como popcretas, uma vez que igualmente solapavam o racionalismo concreto. Como já aludiu Aracy Amaral, o uso de materiais e objetos industrializados por Leirner[1], a racionalidade “de base” percebida em seus trabalhos à época, também são afetados por uma astúcia impregnada de ironia. Aqueles seus trabalhos, ao invés de projetarem um devir para o espectador e para a sociedade, instauravam o desarranjo do aqui e do agora (Você faz parte II, de 1964, é um exemplo desta situação).

Distúrbios semelhantes no reinado das vertentes construtivas brasileiras causaram as obras produzidas por Waltercio Caldas nos anos 1970. Críticos à dimensão idealizada da arte, tão estimada pelos concretos, e à ideologia da “arte participativa” pelos neoconcretos, os “aparelhos” de Caldas significaram (e ainda significam) um divisor de águas no âmbito da arte brasileira contemporânea[2].

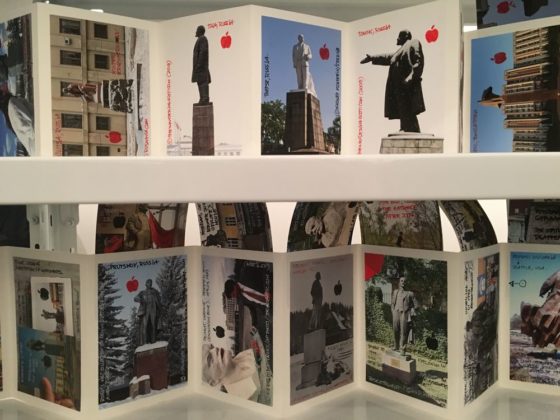

Durante os anos 1970 também chama a atenção a série Cartemas, de Aloisio Magalhães. Com a série, Magalhães propunha a possibilidade de qualquer pessoa produzir obras de arte a partir do rompimento do conceito tradicional de “artista”, não pelo cálculo programado dos concretos e nem pela teatralização da vida dos neoconcretos, mas por meio da manipulação de certos objetos da sociedade de massa (no caso, os cartões-postais).

***

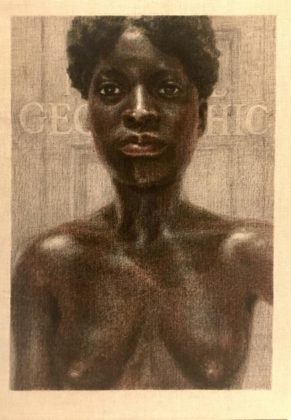

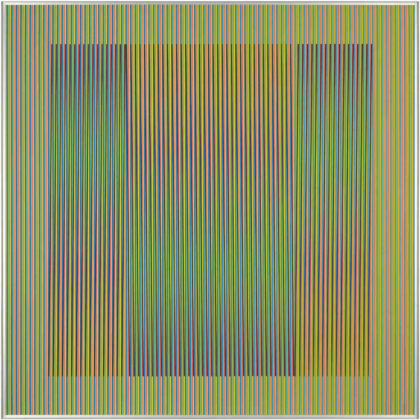

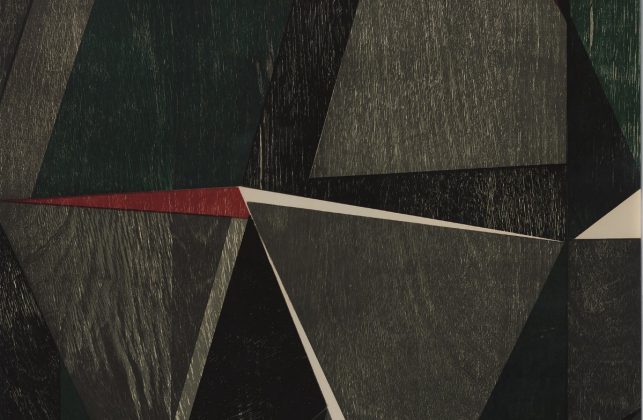

Se as obras citadas configuraram críticas às formulações concretas e neoconcretas, não se deve ignorar outros reparos que a elas foram agregados, porém sem nenhum tipo de negatividade, pelo contrário. Refiro-me às produções de Rubem Valentim e Emanoel Araújo que, a partir dos anos 1960, atentavam para a existência de uma inteligência construtiva no âmbito da visualidade afro-brasileira. Visualidade essa que, com sua simples presença, alargava, por sua vez, a compreensão do que poderia vir a ser aquela “vontade construtiva” no Brasil, acrescentando-lhe um tipo de experiência que até então sobrevivia à margem da arte brasileira branca e hegemônica.

Porém, esse outro caminho apontado pelas obras de Valentim e Araújo parece não ter extrapolado os limites das produções de ambos. Morto Rubem Valentim, sua obra permanece à espera não apenas de estudiosos que se debrucem sobre suas potencialidades de sentido[3], mas, igualmente outros artistas que a adotem como parâmetro, quer positivo, quer negativo (não importa). Hoje em dia, ao que parece, essa vertente se processa apenas na continuidade da produção de Emanoel Araújo, sempre atingindo momentos significativos de interesse estético e artístico.

***

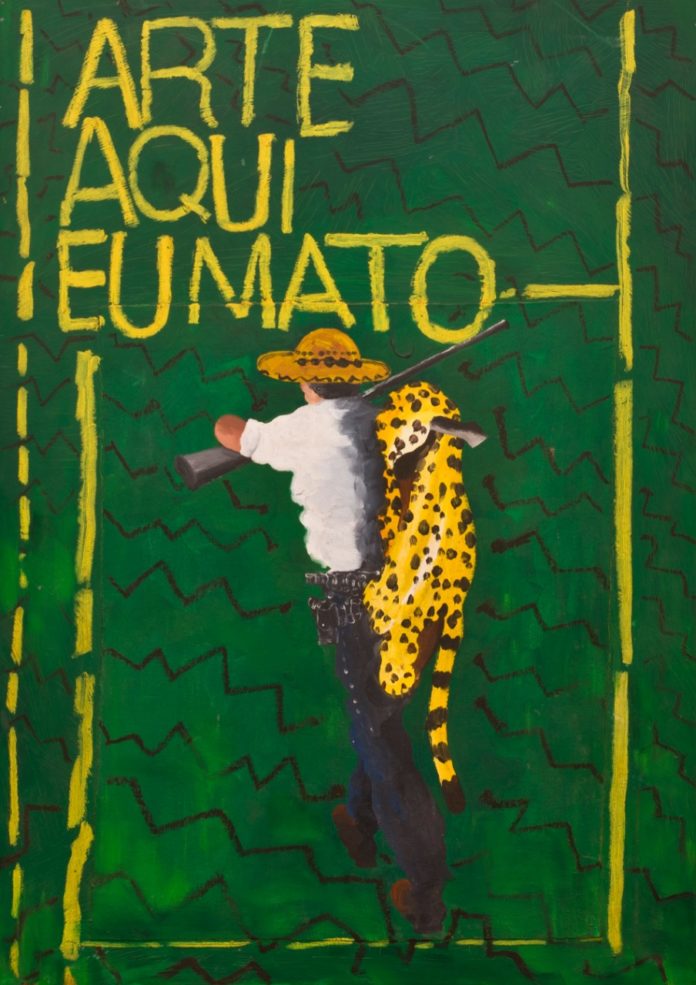

A crítica às vertentes construtivas que Nelson Leirner produziu nos anos 1960 não foi um ato único em sua carreira. Contra o processo de transformação daquelas vertentes em balizas e parâmetros para a arte brasileira, nos anos 1990 o artista produziu uma série intitulada Construtivismo rural, composta por obras que refaziam, em couro bovino, obras emblemáticas daquelas vertentes. Passados vinte anos, elas ainda são significativas por duas razões:

1 – Os movimentos concreto e neoconcreto estabilizaram-se no topo do panteão da arte local;

2 – A associação entre aquelas vertentes e o couro bovino seria uma alegoria da possível convergência entre a arte e o grande capital do país? Ou seja: o agronegócio, além de pop, poderia ser popcreto também?

***

Neste inventário interessam também as produções de três artistas: Luiz Hermano, Shirley Paes Leme e Gustavo Rezende que, entre o final dos anos 1990 e início do novo século, desenvolveram produções que lidavam com os limites, tanto das vertentes construtivas (e não apenas aquelas aclimatadas no Brasil) como também de determinadas poéticas individuais delas derivadas. São do final dos anos 1990 as séries de trabalhos de Hermano e Paes Leme, em que os artistas questionam algumas das propostas construtivas, a partir de obras que, ao solaparem a configuração perfeita do cubo e outros poliedros, questionam a racionalidade que os celebra. A lógica “industrial” entrelaçada àquela “artesanal” sintetizam as contradições do país, entre o projetar para o novo e o mover-se no arcaico.

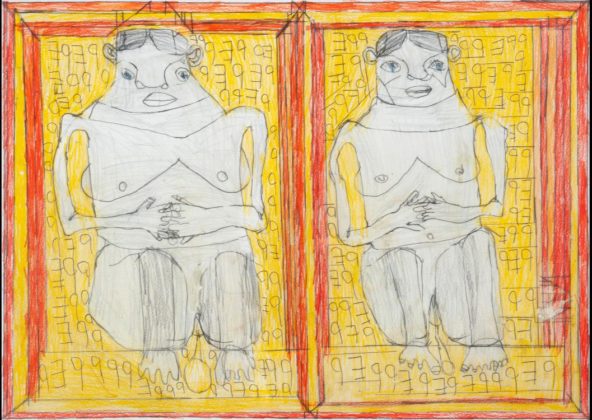

Gustavo Rezende, por sua vez, em 2000, produziu algumas obras em que, ao problematizar uma das ferramentas principais do pensamento plástico construtivo – o módulo –, “semantiza” a tradição construtiva local a partir de um sarcasmo para além da mera ironia. Neste sentido, vale a pena rever suas obras Hero e Taj Mahal e a possibilidade do amor na era do cubo epistemológico (duas versões) – esta última tendo como módulo uma caixa de Prozac.

***

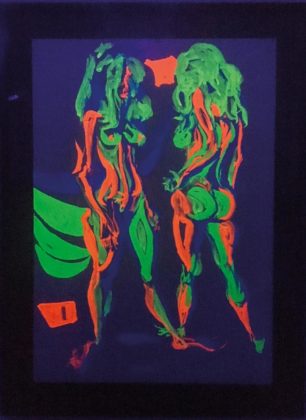

Recentemente, a artista Lyz Parayzo desenvolve suas Bixinhas, transformando os Bichos de Lygia Clark – produzidos para a relação pacífica entre espectador e obra de arte – em armas de ataque. Suas Bixinhas, por sua vez, misturam-se às outras obras da artista, belos e perigosos adornos para seduzir e se proteger dos protagonistas da cultura transfóbica do Rio de Janeiro.

***

Fechando esse arrolamento, destacam-se as produções de dois artistas mais recentemente introduzidos na corrente principal da arte brasileira: Rosana Paulino e Jaime Lauriano.

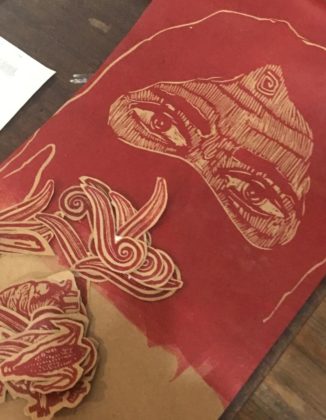

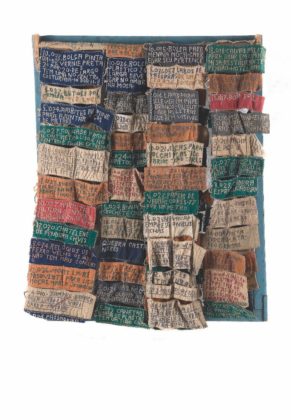

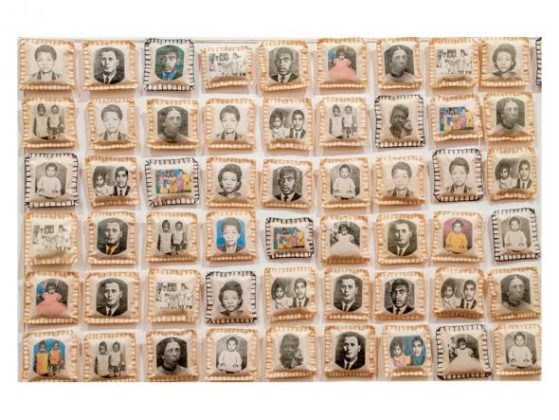

Em Paulino, percebe-se, desde Parede da memória (1994/2015), como ela contamina a grade modernista e sua modalidade formal mais praticada desde a pop e a minimal – obras produzidas a partir da justaposição de módulos –, introduzindo em cada elemento de Parede da memória índices de uma vivência carregada de historicidade, visíveis não apenas nas imagens usadas pela artista em cada módulo, mas também na própria construção de cada um deles. Mais recentemente, Paulino tem ido diretamente ao ponto com as séries Geometria à brasileira e A geometria brasileira chega ao paraíso tropical, ambas de 2018. Nessas colagens/monotipias em impressões digitais, a artista “semantiza” a ordem concretista/neoconcretista, impregnando-a de imagens oriundas da flora, da fauna e do universo de pessoas que um dia viveram escravizadas no Brasil.

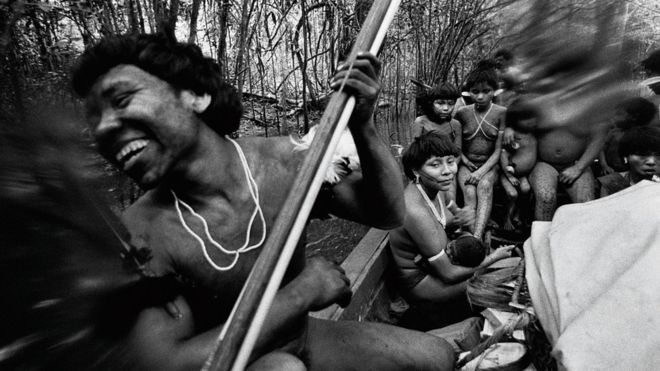

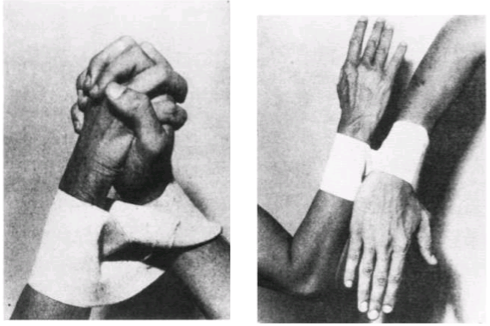

Por sua vez, desde 2017 Jaime Lauriano desenvolve uma série intitulada Experiência concreta, colagens a partir de vários materiais e suportes. Em Experiência concreta #7, por exemplo, emula soluções concreta e/ou neoconcreta para discutir a história dos povos negros escravizados. Em Experiência concreta #1, 2017, o artista, ao operar sobre a foto da performance Diálogos de mãos (1966), de Lygia Clark, traz outra possibilidade para a “semantização” de imagens-emblemas do neoconcretismo.

Ao finalizar esse arrolamento atentando para o fato de que os três últimos artistas comentados provém de universos até há pouco tempo distantes do universo das artes visuais do Brasil. Lyz Parayzo é uma artista trans, Rosana Paulino e Jaime Lauriano são artistas afrodescendentes.

Nesta década, os três conseguiram forçar as portas do ambiente artístico local, mobilizados não apenas pela potência de suas produções, mas também pelo caráter novidadeiro do mercado e – não podemos esquecer – pelo clima de revisionismo histórico, de tolerância e acolhimento do “outro” em que vivemos no Brasil nos últimos anos. Mas, apesar da aparente absorção de suas produções, a pesada carga de conteúdo que elas trouxeram para dentro de uma história da arte apenas preocupada com a busca da depuração formal, da expressão do “eu” do artista – ou ainda como pura vivência –, não foi ainda totalmente digerida.

As histórias que esses três artistas contam, apesar de aceitas, incomodam. As críticas negativas aos cânones da arte brasileira contemporânea também. E a pergunta que fica é esta: nesses tempos mais turvos em que adentramos hoje, essas proposições continuarão sendo toleradas?

De qualquer maneira, o arrolamento acima (apesar de seu caráter lacunar) demonstra como é possível traçar uma história da arte contemporânea no Brasil na qual predomina o caráter dissidente ou alheio a dogmas. Agora é ver se essa história terá forças para continuar.

[1] – Arte paulistana (1998). IN AMARAL, Aracy. Textos do Trópico de Capricórnio. Artigos e ensaios. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2006, vol. 3 p. 303.

[2] – Sobre esses trabalhos de Waltercio Caldas, ler: BRITO, Ronaldo. Waltercio Caldas Jr. Aparelhos. Rio de Janeiro: GBM Editoria de Arte, 1979.

[3] – Um primeiro e grande passo neste sentido foi dado pelo MASP que, no segundo semestre de 2018, realizou a mostra Rubem Valentim: Construções afro-atlânticas, que apresentou ao público um importante panorama da obra do artista. Acompanhava a mostra um catálogo em que foram reunidos alguns dos principais textos escritos sobre a obra do artista durante sua vida e, ao mesmo tempo, ensaios inéditos escritos por novos estudiosos.

For medical science

For medical science