By Dereck Marouço, in Berlin

T

he exhibition Love and Ethnology: The Colonial Dialectic of Sensitivity (according to Hubert Fichte) was held in honor of the German author’s series of 19 books that together form a significant body of work on his travel experiences, wrapped between sex and spirituality. The importance of his narrative lies, beyond the documentary and prose character, in the autobiographical force. The project was supported by Goethe Institute and takes place after previous editions in Lisbon, Salvador, Rio de Janeiro, Santiago and Dakar. In Berlin, the project is curated by Diedrich Diederichsen and Anselm Franke, who mixed works exhibited in previous exhibitions with new additions.

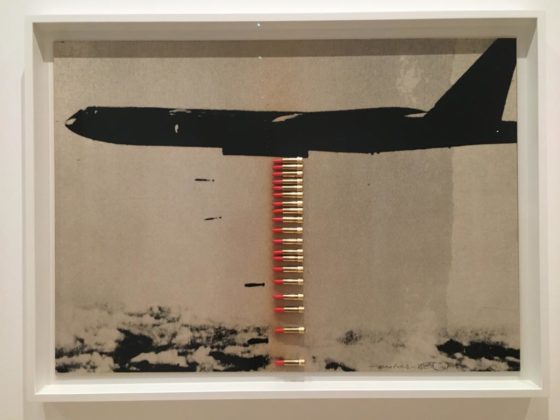

Hubert Fichte (1935 – 1986) lived radically at a crucial time in recent German history. Son of Jewish father, as a child had to hide in a bomb shelter to escape the Nazi threat. He has been to Brazil three times, between 1969 and 1972, having experienced African-Brazilian spiritual practices during this period, as well as many homosexual relations, even living with a woman, the photographer Leonore Mau. It is in this context that he begins to constitute his History of Sensitivity, based on travel as an investigative method, when experiences and impressions are key to a thorough knowledge of other cultures. Fichte was a fringe as being gay was still a crime in Germany in the 1960s. But when traveling to countries with dictatorial regimes in the 70s, such as Brazil, Portugal and Chile, he realizes the real antagonist of his History of Sensitivity: torture and neglect of human rights.

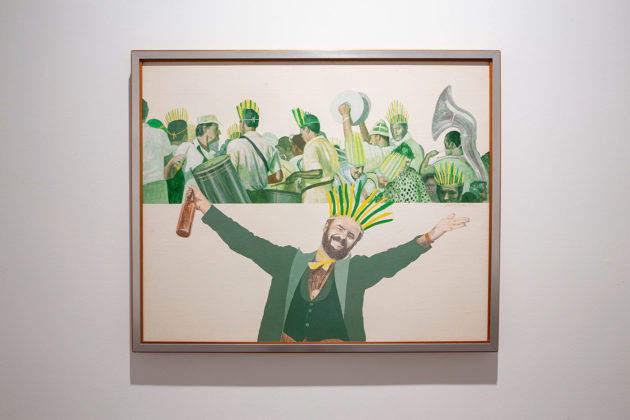

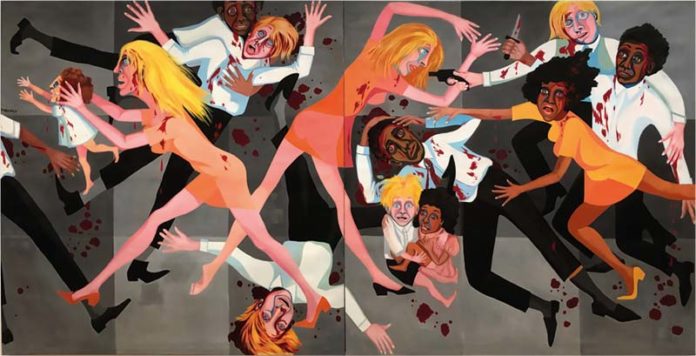

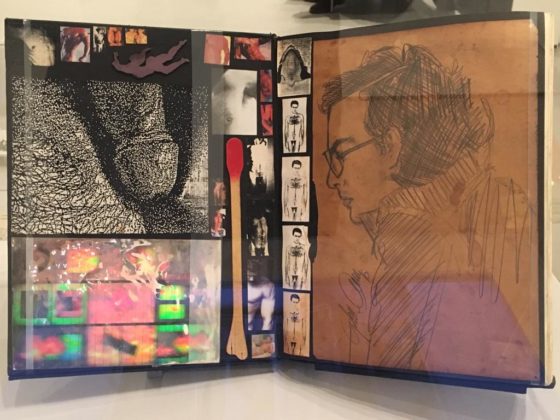

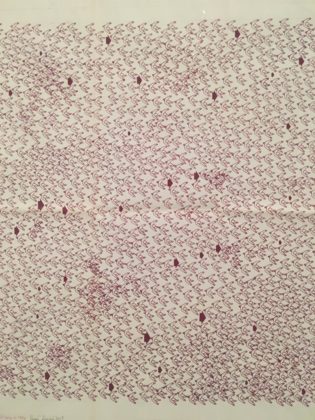

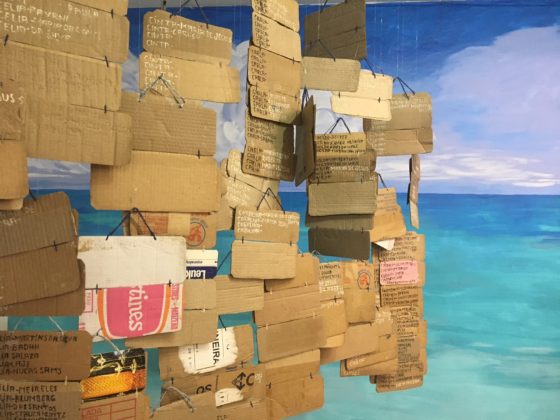

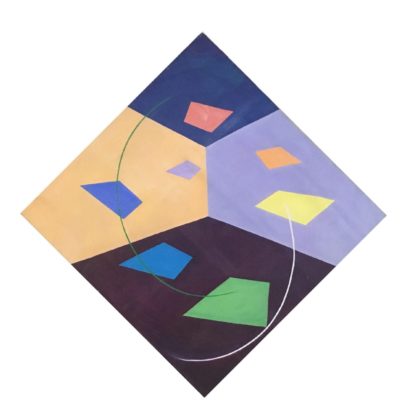

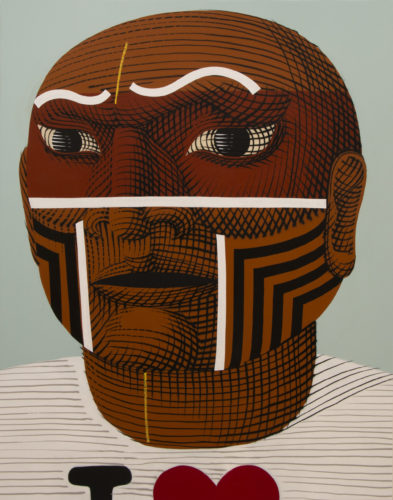

For the exhibition in Berlin, more than 170 works were densely grouped, including painters such as André Pierre (Port-Au-Prince) and Canute Caliste (Trinidad) and Harlem Renaissance artists such as Camille Billops, Owen Dodson & James Van Der Zee to German contemporary media artists such as Michael Buthe. There are also a good number of Brazilian artists in the exhibition: Virginia de Medeiros, Ayrson Heráclito, Miguel Rio Branco, Alair Gomes and the Bonobando group, all exhibited in a cluster, with works by American artists such as Alvin Baltropp and Tione Nekkia McClodden. These two parts are permeated by both interviews and publications by Fichte and other writers in partnership with photographers such as Pierre Verger and his companion Leonore Mau. Another session is devoted to Fichte’s literary influences, with books by Jean Genet, Isabelle Eberhardt, James Baldwin, Pier Paolo Pasolini and William S. Burroughs, literary script that constitutes a queer genealogy.

The opening of the exhibition featured the performance Black Garden / Omindarewa (2017) of the Bonobando group, presented by Lívia Laso, Vanessa Rocha and Adriana Schneider. In it, a black woman creates a narrative from the point of view of Casa das Minas in São Luís do Maranhão, about the clash between religions and cultures, while handling a puppet of a white man. The work subverts the Eurocentric dynamic that imposes itself on other cultural aspects, especially African-American ones.

Tione Nekkia McClodden exhibits the work an Offering | six years | a conjecture (2017), about performing a personal ritual for Shango, interspersed with a video highlighting the misperception of the masses of African-American religions.

Love and sex, recurring themes in Fichte, are portrayed softly in the exhibition. The photos by Alair Gomes, Alvin Baltrop, and Isaac Julien make explicit the sensuality and the proscribed desire, but in these three cases the selected photos always keep a distance between camera and object of appreciation and do not allude to an intimate study when considering the name of the exhibition.

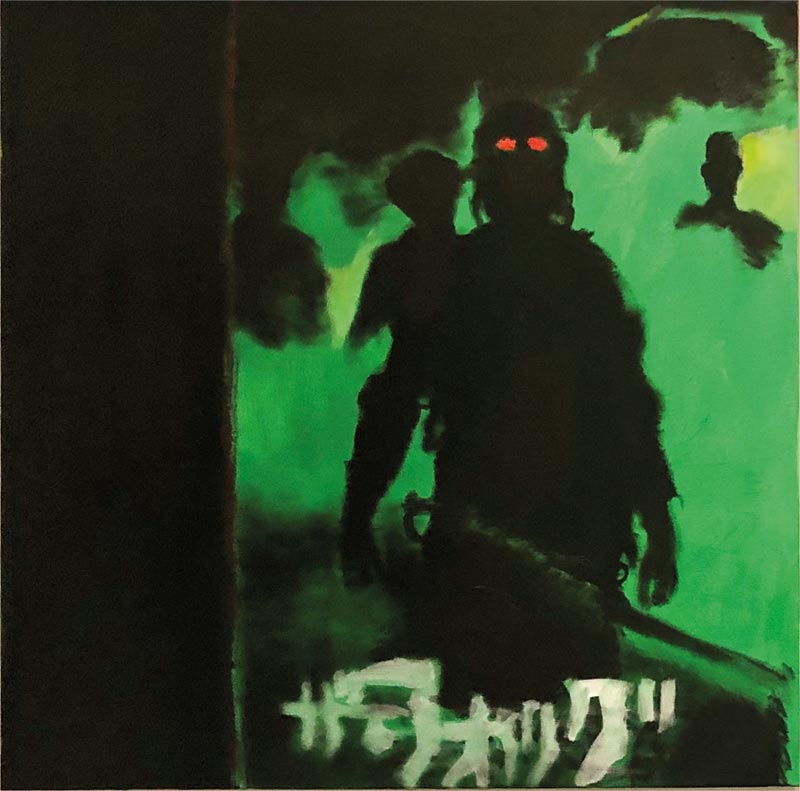

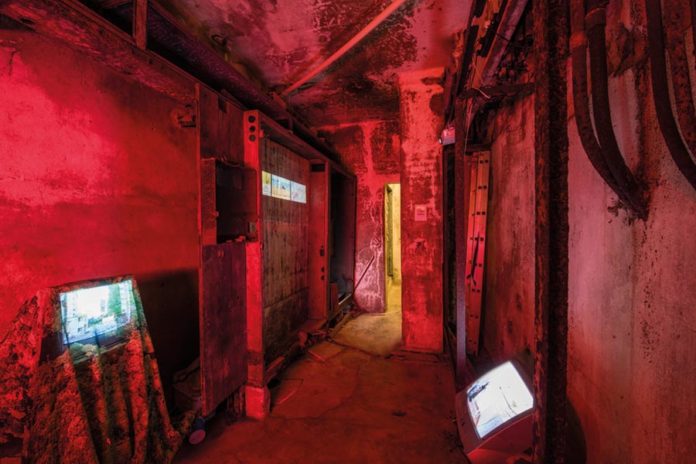

The only works that portray sex closely are Nada Levarei Quando Morrer (1980/1985), by Miguel Rio Branco and Peep Show I-III (2017) also by Bonobando, which chronicles the sexual adventures of Jäcki (biographical character of Fichte) in Brazil with film images accessed through rubber holes. Amid the large number of works, the only ones that make direct mention of the social complexity common to the points of the globe mentioned in the exhibition besides Rio Branco’s is Ayrson Heráclito’s Baia de Todas das Santas (2017). While Rio Branco displays the scarred bodies of Pelourinho, Heráclito brings the sinister streets of beautiful Bahia at night.

Love and Ethnology: The History of Sensitivity uses the body of work written by the German writer and criticizes the European view of underrepresented cultures with an interesting effort of shared curatorships. However, the exhibition does not investigate so much the term “ethnology” beyond the religious cultural meaning, which is also dissociated from its current context, in which spiritual practices are often pursued.

Even presenting a significant set of works, the project lacks the meaning which was experienced by Fichte in his various trips and is inseparable from both the development of black culture and queer culture. The exhibition does not take advantage of his honorees’ experiences to delve into the chosen topics and leaves us an impression that the world has been simplified.

* Dereck Marouço is an art researcher, graduated in Art: History, Criticism and Curator from the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo. Integrate as assistant to curatorship teams of the Pinacoteca of the State of São Paulo and the Museum of Art of São Paulo, assisting in various exhibitions and research. Lives and works in Berlin.