In Ocupar os memes é preciso, the researcher and professor of University of São Paulo, Giselle Beiguelman, resumes the origin of the word “meme”, tracing it back to a time before the internet. The name we use today was coined by the English biologist Richard Dawkins, in 1976, in the book The Selfish Gene. In Dawkins’ theory, as Beiguelman summarizes, “the meme is a replicator unit that spreads by imitation, always subjected to mutation and mixing, and that functions as critical resistance”.

Dislinking itself from its origin, and “back to the future”, the meme as we understand begins to appear in the 2000s and spreads with sharing via social networks. Far from being restricted to pop culture, memes have taken roots to other fields, such as politics, and, gradually, have been operated by propaganda and advertising.

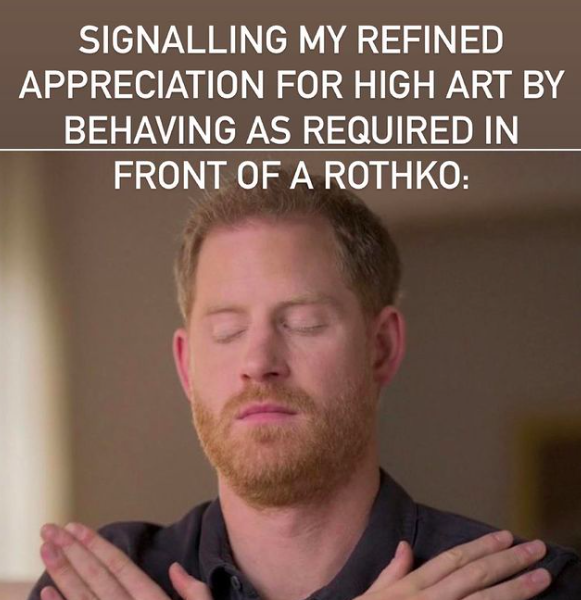

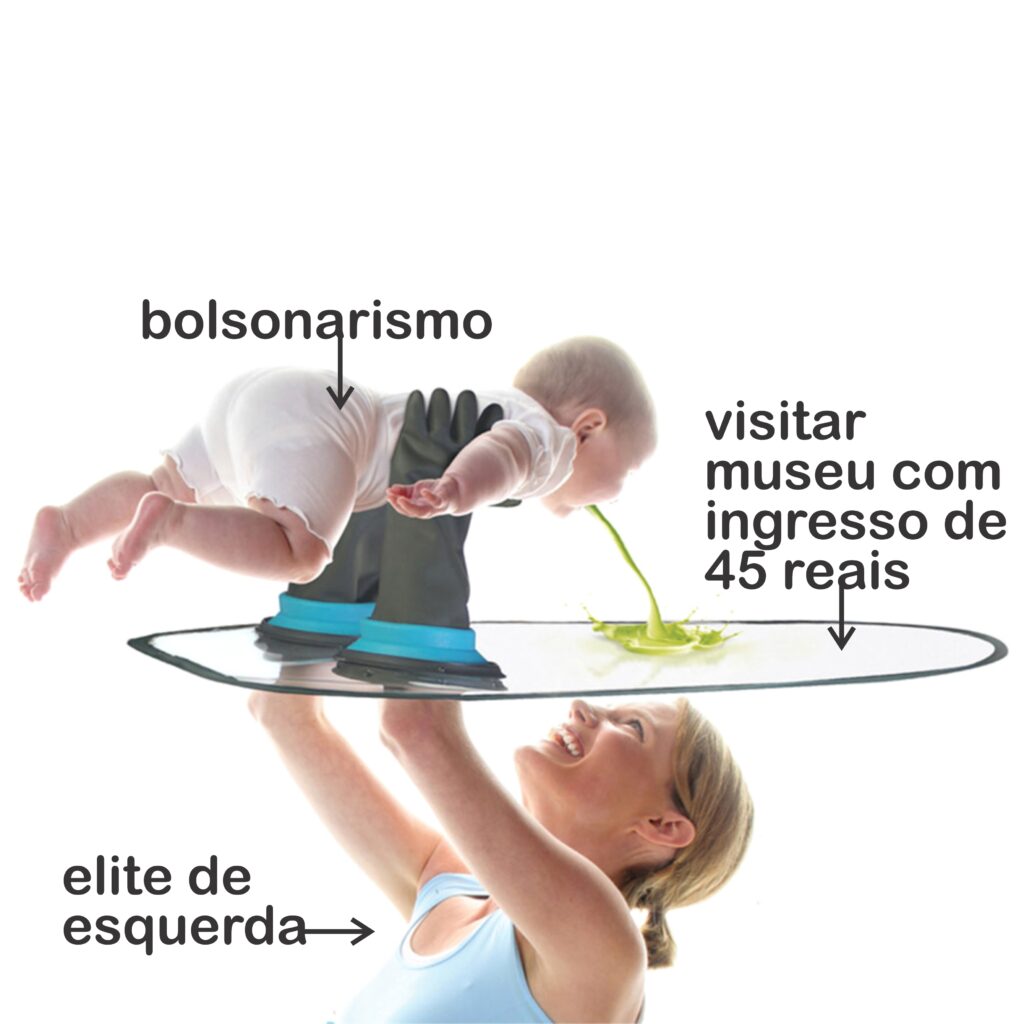

Without imprisoning them in a categorical definition, Beiguelman rather points to their frequent composition: “They present a format in which the text does not function as an explanatory complement to the image nor the image serves merely to illustrate the text, but the two elements chain themselves together to produce a third sense”. On Instagram, in particular, another visual element is included, positioned in a certain “between” – neither completely inside or outside the post – which is the location of the photo, used more and more to add depth to the joke. “Low resolution, bastards and without signature; [memes] are poor images, in the sense given by the German artist and essayist Hito Steyerl to the expression, which can act as a counterpoint to the dominant representation systems”, Beiguelman describes. The Brazilian profile New Memeseum is in line with the argument when it indicates that memes possibly help to formulate narratives different from the hegemonic ones. “Maybe show their unfoldings, contradictions and oppositions”. For them – whose identities are preserved in anonymity – the power of memes lies in their fictional character. “Paraphrasing Karl Ove Knausgård, maybe we are trying to combat fiction with fiction”. At the end of the second volume of the Norwegian writer’s series My Struggle, it reads – and the New Memeseum quotes: “It was a crisis, I felt it in every fibre of my body, something saturating was spreading through my consciousness like lard, not least because the nucleus of all this fiction, whether true or not, was verisimilitude and the distance it held to reality was constant. In other words, it saw the same. This sameness, which was our world, was being mass-produced”.

With regard to this counterposition activity, Cem A. (also known as @freeze_magazine, in parody of the British art magazine) presents the possibility of memes as agents of change, although not in a revolutionist way, but reformist. “Memes should be seen as a tool to popularise forward-thinking ideas. Their popularity can give us the upper hand in the conversation. This is where their strength lies. The crucial danger here is how they might be absorbed by the art market. If memes were commercialised with a short sighted approach, this would only make them less popular, genuine and efficient. It would make me question if they could be considered memes at all”.

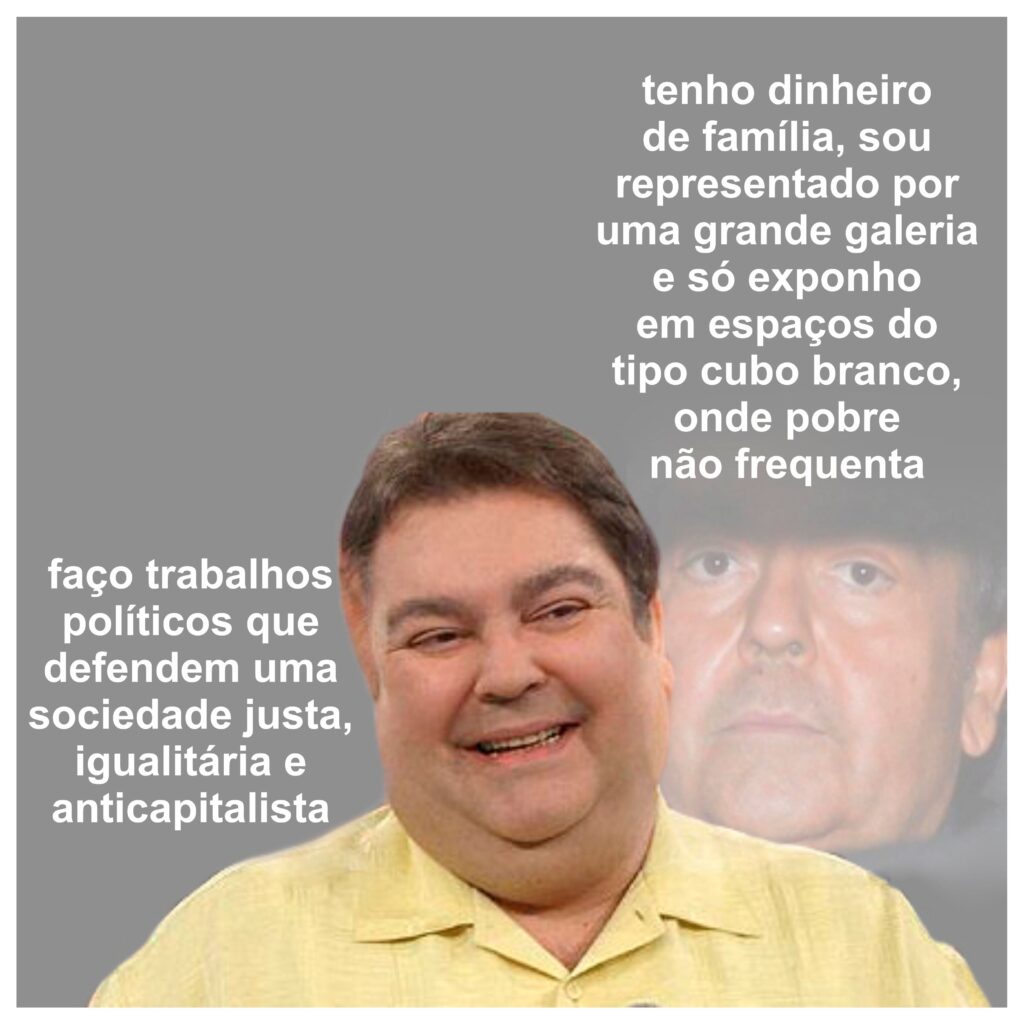

When the establishment begins to swallow memes (which, until then, resisted it with acidic and humorous criticisms), do they lose strength (by integrating what they once have challenged)? An important observation is made by Hilde Lynn Helphenstein, creator of the virtual character Jerry Gogosian (the name alludes to two recognized figures in the art world, the critic Jerry Saltz and the mega gallerist Larry Gagosian): “The ways in which I plan to monetize what I’ve created with @jerrygogosian will be a means to achieve a version of the art world I can live with on a micro-scale. My artistic achievements will be perpetuated by the capitalist machine and I have no problem with that. An artist has to dream big (and eat)”.

“We are not sure whether the institutionalization of memes can cause any impact or change for content creators”, notes New Memeseum, when considering that, perhaps, the impact is on the institutions themselves, who, “by looking with less distinction between high and low culture, are incorporating languages that can attract new audiences into their programming”. Digging deeper, they question whether the narrative could not be told in reverse: from the perspective of social networks, it may be that museums and galleries are the “spaces of exception”, precisely because art is still somewhat inaccessible to the majority of the population [at least in Brazil]. According to what they observe in today’s scenario, institutions have started to seek their space on the Internet, investing and worrying about their virtual platforms.”There is a desire for audience engagement. The economy of likes has also impacted the sources of sponsorship – let’s remember the cultural edict that, recently, assumed as criterion the sum of social media followers of the members from each project”, they add. With these questions put on the horizon, they point out that New Memeseum (in the same way as Jerry and Freeze) is an Instagram profile and, as such, works within an app managed by a trillion-dollar conglomerate. “We also live under the regency of algorithms”.

Under such regency, is humor an effective format to face the established powers?, asks Hilde, to which she herself responds negatively. “Being the jester who states the obvious to the court in the presence of the king is still beholden to the king. Humor is a medicine which temporarily soothes the pain of those not in power and creates the illusion of taking back control. Taking money from the powers that be and redistributing wealth is probably the only way to “win” in late stage capitalism…but it feels good to laugh, whether you’re winning or losing”. In The Value of Laughter, Virginia Woolf expresses that laughter preserves our sense of proportion, recalls New Memeseum. In Woolf’s words: “Dogs, mercifully, cannot laugh, because, if they could, they would realise the terrible limitations of being a dog. Men and women are just high enough in the scale of civilisation to be intrusted with the power of knowing their own failings and have been granted the gift of laughing at them”. In that same text, reminding us of the importance of proportion, the British writer ends up also mentioning the nonexistence of a “complete hero”, the one who needs to be put on a pedestal.

The “complete hero”, does it look like a pretension familiar to some figures in the art world? Such self-mythologized characters, not rarely, make up the cast of this memetic play. Is it possible, though, to get them off the pinnacle and back to proportion? “We don’t know if the satire of institutions and their characters by arts-related memes make these same characters/elements more accessible”, confesses New Memeseum. “Perhaps, it makes more visible the narrative plot in which they are involved: the problems, weaknesses, contradictions, professional and personal dramas etc”.

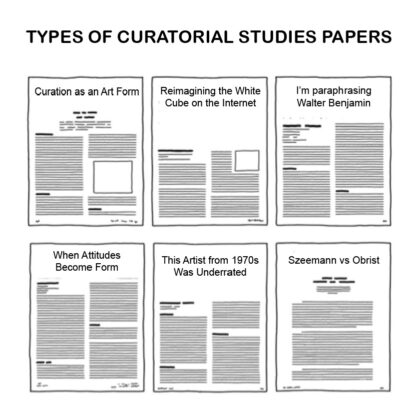

If not to demystify the linguist, can memes decode their language? For Cem A., memes can be useful both for communicating complex ideas and for criticizing inaccessible texts – frequent in the art world – when they don’t fight hard enough to win their reader. To the latter, Hilde refers to as “show off texts where people are really proud to show you they have a master’s degree in polysyllabic words”.

“I think that this sort of language is used as an intimidation tactic and rarely are the people wielding this language in full control of what they say. If they were, they’d say much less in a smoother, more palatable way”, she states and, wittily, poses the question: “Have you ever heard of a meme?”. According to Jerry Gogosian’s creator, “you do need cultural literacy to understand memes as well as a general sense of the topic, but you can learn to read them rather quickly and there’s not grammar to learn (please see how poorly I spell in my memes)”.

For New Memeseum, the memetic panorama is too diverse to state categorically that memes make something more accessible, and can be as or more truncated than many curatorial texts or artists’ speeches. “Sometimes the reception of memes ranges from ‘ok, I get it’ to ‘what does that really mean?’ – there’s a wide spectrum between transparency and opacity and that makes this language so interesting to work with”.

Such nuance combined with humor allows memes to address important issues, sometimes relegated by consolidated media and/or cultural commentators. The anonymity of the producers of memes (Hilde had her identity revealed against her will, in fact, in an Artnet article, whose writer did not get the memo, nor the joke) along with their irreverence and the release from the pretense heroes of the art world, really allow them cross narrower corridors.

“ It is nearly impossible to run a sustainable business in the art world. Media outlets are included in this too. So I can see why their editorial choices tend to be conservative. Having said that, I don’t agree with their approach at all”, says Cem A. when I mention the case of the exhibition Arte em Campo, held in late 2020 and reported on with the neutrality of a detergent. The event brought together about 25 galleries and 54 artists to celebrate the “new Pacaembu”, the result of its concession to the private sector for 35 years. It was the opportunity to “say goodbye” to the beloved stadium that would have, months later, the area that housed its most affordable tickets demolished. Curator Pollyana Quintella tells she wondered what role the exhibition played there, in addition to camouflaging, “sophisticating” and providing “a cool façade that would justify interests that were far from the ones favoring the city [and the public interest, rather than the private sector]”. Therefore, this kind of news – or distribution of “merely carefully crafted pieces of PR”,” as Hilde describes it – also gets on the radar of meme creators.

Taking advantage of the busted art ♡ neoliberalism affair, Cem A. does not cease to draw attention to the “invisible work” of digital projects: “People often overlook the time and effort it takes to put together a digital project. Memes are included in this too. The pandemic showed us that the internet is now an integral part of the art ecosystem and often can reach bigger audiences than what is possible in the physical world. We need to do more to address the financial inequalities in this paradox and compensate digital-first artists more fairly”.

To approach the elephant in the room before finishing this article: after all, memes are art? “We often think that, no matter how far away, they have some connection with the conceptualism of the 1960s and 1970s, especially with regard to operations performed between word and image”, notes New Memeseum. Cem A. believes that memes should be recognized in the context of art because they carry aesthetic and conceptual qualities. “However, this doesn’t necessarily mean they should be considered artworks or as ‘contemporary art’”, and stresses: “In fact, we should collectively question the assumption that contemporary art stands on a higher level”. This and the other issues mentioned above might still gain momentum. “We believe that nothing has been exhausted [in relation to memes] because, in art, these debates have barely begun”, the Brazilian meme creators reiterate.

Read more about art and the digital world, click here.

Detalhes

A Olho Nu, maior retrospectiva realizada pelo prestigiado artista brasileiro Vik Muniz chega ao Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Bahia (MAC_Bahia). Com mais de 200 obras distribuídas em 37 séries, A

Detalhes

A Olho Nu, maior retrospectiva realizada pelo prestigiado artista brasileiro Vik Muniz chega ao Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Bahia (MAC_Bahia).

Com mais de 200 obras distribuídas em 37 séries, A Olho Nu reúne trabalhos fundamentais de diferentes fases da trajetória de Vik Muniz, reconhecido internacionalmente por sua capacidade de transformar materiais cotidianos em imagens de forte impacto visual e simbólico. Chocolate, açúcar, poeira, lixo, fragmentos de revista e arame são alguns dos elementos que integram seu vocabulário artístico e aproximam sua produção tanto da arte pop quanto da vida cotidiana. O público poderá acompanhar desde seus primeiros experimentos escultóricos até obras que marcam a consolidação da fotografia como eixo central de sua criação.

Entre os destaques, a exposição traz quatro peças inéditas ao MAC_Bahia, que não integraram a etapa de Recife: Queijo (Cheese), Patins (Skates), Ninho de Ouro (Golden Nest) e Suvenir nº 18. A mostra apresenta também obras nunca exibidas no Brasil, como Oklahoma, Menino 2 e Neurônios 2, vistas anteriormente apenas nos Estados Unidos.

A retrospectiva ocupa o MAC_Bahia e se expande para outros dois espaços da cidade: o ateliê do artista, no Santo Antônio Além do Carmo, que receberá encontros e visitas especiais, e a Galeria Lugar Comum, na Feira de São Joaquim, onde será exibida uma instalação inédita inspirada na obra Nail Fetish. Esta é a primeira vez que Vik Muniz apresenta um trabalho no local, reforçando o diálogo entre sua produção e territórios populares de Salvador.

Exposição A Olho Nu, de Vik Muniz, no Museu de Arte Contemporânea. Foto: Vik Muniz

Apontada como fundamental para compreender a transição do artista do objeto para a fotografia, a série Relicário (1989–2025) recebe o visitante logo na entrada do MAC_Bahia. Não exibida desde 2014, ela apresenta esculturas tridimensionais que ajudam a entender a virada conceitual de Muniz, quando o artista percebeu que podia construir cenas pensadas exclusivamente para serem fotografadas, movimento que redefiniu sua carreira internacional.

Para o curador Daniel Rangel, também diretor do MAC_Bahia, a chegada de A Olho Nu tem significado especial. “Essa é a primeira grande retrospectiva dedicada ao trabalho de Vik Muniz, com um recorte pensado para criar um diálogo entre suas obras e a cultura da região”, afirma.

A chegada da retrospectiva a Salvador também fortalece a parceria entre o IPAC e o Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil (CCBB), responsável pela realização da mostra e em processo avançado de implantação de sua unidade no Palácio da Aclamação, prédio histórico sob gestão do Instituto. Antes mesmo de abrir suas portas oficialmente na Bahia, o CCBB Salvador já vem promovendo ações culturais na capital, entre elas a apresentação da maior exposição dedicada ao artista.

Para receber A Olho nu, o IPAC e o MAC_Bahia mobilizam uma estrutura completa que inclui serviços de manutenção, segurança, limpeza, iluminação museológica e logística operacional, além da atuação da equipe de mediação e das ações educativas voltadas para escolas, universidades, grupos culturais e visitantes em geral. A expectativa é de que o museu receba cerca de 400 pessoas por dia durante o período da mostra, consolidando o MAC_Bahia como um dos principais equipamentos de circulação de arte contemporânea no Nordeste. Não por acaso, o Museu está indicado entre as melhores instituições de 2025 pela Revista Continente.

Com acesso gratuito e programação educativa contínua, A Olho Nu deve movimentar intensamente a agenda cultural de Salvador nos próximos meses. A exposição oferece ao público a oportunidade de mergulhar na obra de um dos artistas brasileiros mais celebrados da atualidade e de experimentar diferentes etapas de seu processo criativo, reafirmando o MAC_Bahia como referência na promoção de grandes mostras nacionais e internacionais.

Serviço

Exposição | A Olho Nu

De 13 de dezembro a 29 de março

Terça a domingo, das 10h às 20h

Período

Local

MAC Bahia

Rua da Graça, 284, Graça – Salvador, BA

Detalhes

“O desencaixar das coisas” é a exposição inaugural da Pórtico e apresenta trabalhos de 16 artistas. Com uma seleção que inclui nomes emergentes e consagrados de distintas gerações e geografias,

Detalhes

“O desencaixar das coisas” é a exposição inaugural da Pórtico e apresenta trabalhos de 16 artistas. Com uma seleção que inclui nomes emergentes e consagrados de distintas gerações e geografias, a mostra serve como um prelúdio para a série de exposições e a programação da galeria no ciclo de 2026, refletindo a amplitude de perspectivas que orientam o projeto.

São eles: Angela Bassan (São Paulo, 1952), Caio Borges (São Paulo, 1974), Edson Chagas (Luanda, 1977), Gege Mbakudi (Luanda, 1999), Giovanna Mitrani (São Paulo, 1997), Hugo Barata (Lisboa, 1978), Inês Moura (Cascais, 1982), José Maçãs de Carvalho (Anadia, 1960), Laerte Ramos (São Paulo, 1978), Lilian Walker (Americana, 1994), Lucimélia Romão (Jacareí, 1988), Manoel Canada (São Paulo, 1966), Neno del Castillo (Rio de Janeiro, 1956 ), Omar Khouri (Pirajuí, 1948), Peter de Brito (Gastão Vidigal, 1967) e Ricardo Coelho (São Paulo, 1974).

A exposição – além de acreditar na força de objetos como as fotografias de artistas como Lucimélia Romão e o artista angolano vencedor do leão de ouro na Bienal de Veneza em 2013, Edson Chagas, e do vídeo do artista português José Maçãs de Carvalho, que acaba de chegar da Bienal Internacional de Arte de Macau 2025 – também esbanja ocaráter interdisciplinar da galeria, no momento que esta representa nomes, que também poderão desempenhar outras pesquisas durante o ciclo que será apresentado em 2026.

Como exemplo, nomes como o de Omar Khouri, poeta intersemiótico cultuado desde os anos 70, e Inês Moura, participante da mostra Atlânticos que esteve este ano no Museu da Língua Portuguesa, são artistas que deverão atuar em investigações curatoriais e educativas em 2026 junto a direção artística de Adolfo Caboclo. O expertese de nomes como do pintor Manoel Canada – artista, restaurador e historiador da arteque desenvolve pinturas sobre a cidade e o território, reunindo a historiografia de construções e o da escultora Angela Bassan – que trabalhou por duas décadas como artista-educadora no Museu Brasileiro da Escultura e na Faap (Fundação Armando Álvares Penteado), ministrando cursos de Escultura, além de atuar no design de objetos- influenciam nas propostas que serão apresentadas pela Pórtico em 2026.

Serviço

Exposição | O desencaixar das coisas

De 16 de dezembro a 14 de fevereiro

Terça-feira, Quarta-feira, Quinta-feira, Sexta-feira das 10h às 19h, aos sábados, das 10h às 17h

Período

Local

Pórtico

Travessa Dona Paula, 116 – Higienópolis, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A Nara Roesler São Paulo tem o prazer de apresentar Telúricos, exposição coletiva com curadoria de Ana Carolina Ralston que reúne 16 artistas para investigar a força profunda da matéria terrestre

Detalhes

A Nara Roesler São Paulo tem o prazer de apresentar Telúricos, exposição coletiva com curadoria de Ana Carolina Ralston que reúne 16 artistas para investigar a força profunda da matéria terrestre e as relações viscerais entre o corpo humano e o corpo da Terra. A mostra fundamenta-se no conceito de imaginação telúrica, inspirado pelo filósofo Gaston Bachelard, para explorar como a arte pode escavar superfícies e tocar o que há de mais denso e vibrante na natureza e na tecnologia. A exposição propõe um deslocamento do olhar ocular-centrista, convidando o público a uma experiência multissensorial que atravessa o olfato, a audição e a tactilidade. Como afirma a curadora, “a imaginação telúrica cava sempre em profundidade, não se contentando com superfícies”. Em Telúricos, a Terra deixa de ser um cenário passivo para tornar-se protagonista e ator político, transformando nossos modos de habitar.

A seleção curatorial estabelece um diálogo entre nomes históricos da Land Art e vozes contemporâneas, onde a matéria deixa de ser suporte para se tornar corpo e voz. Richard Long representa a tradição da intervenção direta no território, enquanto artistas como Brígida Baltar apresentam obras emblemáticas, como Enterrar é plantar, que reforçam o ciclo de vida e renascimento da matéria. A mostra conta ainda com a presença de Isaac Julien, Not Vital e uma obra em ametista de Amelia Toledo, escolhida por sua ressonância mineral e espiritual. A instalação de C. L. Salvaro simula o interior da Terra através de uma passagem experimental de tela e plantio, evocando arqueologia e memória, enquanto a artista Amorí traz pinturas e esculturas que narram a metamorfose de seu corpo e sua história. A dimensão espiritual e a transitoriedade indígena são exploradas por Kuenan Mayu, que utiliza pigmentos naturais, enquanto Alessandro Fracta, aciona mundos ancestrais e ritualísticos ao realizar trabalhos com bordados em fibra de juta.

A experiência sensorial é um dos pilares da mostra, conduzida especialmente pelo trabalho de Karola Braga, cujas esculturas em cera de abelha exalam os aromas da natureza. Na vitrine da galeria, a estrutura dourada Perfumare, libera fumaça, mimetizando os vapores exalados pelos vulcões, expressão radical da capacidade do planeta de alterar-se, de reinventar sua forma e de impor ritmos. A cosmologia e a sonoridade também se fazem presentes com os neons de Felippe Moraes, que desenham constelações de signos terrestres como Touro, Virgem e Capricórnio, e a dimensão sonora de Denise Alves-Rodrigues. O percurso completa-se com os móbiles da série “Organoide” de Lia Chaia, as paisagens imaginativas de Ana Sant’anna, a materialidade de Flávia Ventura e as investigações sobre a natureza de Felipe Góes. Cada obra funciona como um documento de negociação com o planeta, onde o chão que pisamos também protesta e fala.

Serviço

Exposição | Dada Brasilis

De 05 de fevereiro a 12 de março

Segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h, sábado, das 11h às 15h

Período

Local

Galeria Nara Roesler - SP

Avenida Europa, 655, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

Primeira exposição individual de Daniel Barreto na Bahia. Nascido no Rio de Janeiro, o artista apresenta pela primeira vez seu trabalho ao público soteropolitano. O título da mostra, inspirado em uma

Detalhes

Primeira exposição individual de Daniel Barreto na Bahia. Nascido no Rio de Janeiro, o artista apresenta pela primeira vez seu trabalho ao público soteropolitano.

O título da mostra, inspirado em uma frase do romance Capitães de Areia, de Jorge Amado, orienta uma leitura sensível sobre corpo, território e memória, sob curadoria de Victor Gorgulho.

A exposição ocupa o espaço projetado por Lina Bo Bardi como anexo ao Teatro Gregório de Mattos, em diálogo direto com a paisagem urbana da Praça Castro Alves e a Baía de Todos-os-Santos.

Serviço

Exposição | Pinóia

De 13 de janeiro a 28 de fevereiro

Quarta a Domingo, das 14h às 21h

Período

Local

Teatro Gregório Mattos - Galeria da Cidade

Praça Castro Alves, s/n, Centro, Salvador - BA

Detalhes

Com curadoria de Osmar Paulino, Marlon Amaro expõe Mirongar, mostra reúne obras centrais de sua trajetória, reconhecido por abordar de forma contundente temas como o racismo estrutural, o apagamento da

Detalhes

Com curadoria de Osmar Paulino, Marlon Amaro expõe Mirongar, mostra reúne obras centrais de sua trajetória, reconhecido por abordar de forma contundente temas como o racismo estrutural, o apagamento da população negra e as dinâmicas históricas de violência e subserviência impostas a corpos negros.

Serviço

Exposição | Mirongar

De 13 de janeiro a 21 de março

Quarta a Domingo, das 14h às 21h

Período

Local

Casa do Benin

Rua Padre Agostinho Gomes, 17 - Pelourinho, Salvador - BA

Detalhes

Cheiro de terra molhada, canto de pássaros, sons da mata e imagens da floresta amazônica e de seus habitantes chegam ao Rio de Janeiro para proporcionar um passeio pela maior

Detalhes

Cheiro de terra molhada, canto de pássaros, sons da mata e imagens da floresta amazônica e de seus habitantes chegam ao Rio de Janeiro para proporcionar um passeio pela maior floresta tropical do mundo, na exposição “Presenças na Amazônia: um diário visual de Bob Wolfenson“, no lounge do Museu do Amanhã, no Rio de Janeiro. A mostra fotográfica e multissensorial propõe uma vivência sensível da floresta a partir do olhar artístico do fotógrafo Bob Wolfenson, que completa 55 anos de carreira. Realizada pela Vale, a exposição fica aberta ao público de 15 de janeiro a 10 de fevereiro.

A mostra apresenta as impressões da floresta registradas pelo fotógrafo durante as filmagens da websérie “Amazônia: Juntos Fazemos a Diferença”, conduzida por ele e pela cantora Gaby Amarantos, em 2024. A produção audiovisual, realizada pela Vale, se transformou em uma campanha que apresenta a cultura, a economia, os biomas e o povo da floresta amazônica e se encerra com a estreia da exposição do diário visual de Bob Wolfenson.

“Há quatro décadas a Vale está presente na Amazônia, como um dos principais agentes de desenvolvimento sustentável e de preservação, valorização e difusão da cultura amazônida. Realizamos uma série de iniciativas que fomentam a bioeconomia, protegem a floresta em pé e contribuem com pesquisa e produção de conhecimento em áreas como biodiversidade, genômica e mudanças climáticas. Nesse sentido, a realização dessa exposição no Museu do Amanhã ganha especial propósito, ao propor novas formas de ver e conhecer a região em toda a sua diversidade, provocar reflexões e novas formas de atuarmos, juntos, pelo presente e pelo futuro”, afirma Grazielle Parenti, Vice-Presidente Executiva de Sustentabilidade da Vale.

Organizadas em três eixos – A Floresta, Presenças e Luz Mágica – as fotos revelam a Amazônia por dentro, suas histórias e suas comunidades, em uma narrativa na qual a floresta e as pessoas se misturam e convivem em harmonia.

“Fotografar a Amazônia foi uma experiência profunda e transformadora. Estar diante de uma natureza tão poderosa e, ao mesmo tempo, encontrar pessoas que trabalham para que ela permaneça em pé trouxe um novo sentido ao meu olhar. Levar essas imagens para o Museu do Amanhã, com o patrocínio da Vale, é muito significativo: é uma forma de ampliar esse diálogo e mostrar que preservar a floresta é também preservar histórias, culturas e futuros”, comenta Bob Wolfenson.

“O Museu do Amanhã aposta na força da arte em comunicar o que a ciência hoje demonstra e, com isso, facilitar a reconexão do humano com o oceano”, afirma Fabio Scarano, curador do Museu do Amanhã.

Os espaços são marcados por materiais rústicos e naturais e por uma iluminação que muda ao longo do percurso, remetendo ao ciclo do dia. A experiência ganha profundidade com a presença de elementos sensoriais que transportam os convidados para dentro da Amazônia, como um leve aroma de terra fresca depois da chuva. Também o visitante poderá ouvir sons originais da floresta, fruto de estudo do Instituto Tecnológico Vale (ITV), que reuniu mais de 16 mil minutos da vida na Floresta de Carajás e revelou curiosidades sobre a biodiversidade amazônica por meio do som que ela emite. Além disso, uma área de pausa e contemplação traz frases, trechos de falas e anotações de viagem de Bob Wolfenson, criando uma instalação poética que traduz o processo criativo do artista. A produção é da Tantas Projetos Culturais e TM1 Brand Experience, com curadoria de Cecilia Bedê.

A exposição contará com uma programação educativa e gratuita que conecta as fotografias às memórias, aromas, sons e símbolos da Amazônia. Além da caminhada fotográfica com Bob Wolfenson na Praça Mauá, haverá atividades para todos os públicos, trazendo o DNA amazônico em oficinas de carimbos, aula de dança de carimbó, pintura de brinquedos de miriti e experiências sensoriais como o tradicional banho de cheiro. A programação completa está disponível no site do Museu do Amanhã.

Com atenção especial à acessibilidade e à inclusão, a exposição conta com recursos como obras táteis, dispositivos sonoros e olfativos, mediações, audiodescrição, interpretação em Libras e atividades adaptadas.

Serviço

Exposição | Presenças na Amazônia: um diário visual de Bob Wolfenson

De 15 de janeiro a 10 de fevereiro

Todos os dias, exceto quarta-feira, das 10h às 18h (última entrada às 17h)

Período

Local

Museu do Amanhã

Praça Mauá, 1 - Centro, Rio de Janeiro - RJ

Detalhes

O Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil Belo Horizonte (CCBB BH) apresenta Festa no Céu – Mirĩ’kʉã ʉmʉhsé’pʉ Bahsa’rã, instalação inédita da artista, curadora e ativista indígena Daiara Tukano. A obra

Detalhes

O Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil Belo Horizonte (CCBB BH) apresenta Festa no Céu – Mirĩ’kʉã ʉmʉhsé’pʉ Bahsa’rã, instalação inédita da artista, curadora e ativista indígena Daiara Tukano. A obra ocupa o pátio do centro cultural com um arco composto por mais de 100 pássaros, em sua maioria araras, criado como homenagem à sabedoria ancestral, à preservação da floresta e ao papel das aves como intermediárias entre dimensões espirituais.

O trabalho se estrutura como um grande móbile, no qual os pássaros aparecem em quatro posições distintas, sugerindo movimento contínuo. Feitas em material translúcido e ornamentadas com desenhos de hori em diversos tons, as peças projetam cores no espaço tanto sob a luz do sol quanto à noite, quando recebem iluminação especial. Mais que um conjunto escultórico, a instalação se propõe a funcionar como um portal para a cosmovisão indígena.

Nas narrativas de criação do povo Yepá Mahsã Tukano, antes da multiplicação da humanidade, as Amõ Numiã, as primeiras mulheres, deram à luz os pássaros, que surgiram cantando, voando e espalhando cores pelo mundo. Encantados com esse nascimento, homens e animais passaram a cantar na floresta, cada um em sua própria língua, e a ter mirações, visões coloridas que originaram suas pinturas e desenhos. Assim surgiu a diversidade de povos e percepções que tornou possível a expansão humana. Desde então, os pássaros fazem a festa no céu, levando mensagens e sonhos em seus cantos e revoadas.

“A ‘Festa no Céu’ é um grande móbile de pássaros de acrílico, araras e outros passarinhos voando com as suas asas abertas, desenhadas com Hori, que são os nossos grafismos do povo Ye’pá Mahsã. É uma obra que conta a história da criação dos pássaros, do surgimento das cores, dos desenhos, da arte, das línguas, da beleza, da memória e dos sonhos. São grafismos que nós usamos nas nossas panelas, nas nossas cestarias e nas nossas pinturas corporais, e que fazem parte da nossa cultura. Os pássaros são transparentes e têm reflexos iridescentes, de arco-íris, projetando as suas sombras iluminadas no chão. Eles são transparentes, assim como são transparentes nossos sonhos, nossos pensamentos e nossos sentimentos”, explica Daiara Tukano.

Ao trazer esse símbolo amazônico para um espaço central da cidade como o CCBB BH, a artista reforça a urgência de cuidar da floresta, compreendida por muitos povos como um organismo vivo cujo desequilíbrio manifesta crises espirituais profundas.

Com direção artística e curadoria de Juliana Flores e arquitetura de Camila Schmidt, a instalação integra a ação de final de ano do CCBB BH, fortalecendo a relação do museu com o público que circula diariamente pelo Circuito Liberdade.

Para a gerente geral do centro cultural, Gislane Tanaka, “Festa no Céu nasce em diálogo com a tradicional iluminação de final de ano da Praça da Liberdade, e revela a diversidade de visões que os povos originários guardam como sabedoria, abrindo espaço para um encontro sensível com suas cosmovisões. Nesta travessia entre luz, arte e ancestralidade, o CCBB BH reafirma seu compromisso de aproximar cada vez mais as pessoas da cultura”.

Serviço

Exposição | Festa no Céu – Mirĩ’kʉã ʉmʉhsé’pʉ Bahsa’rã

De 28 de novembro a 28 de fevereiro

Quarta a segunda, das 10h às 22h

Período

Local

Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil Belo Horizonte (CCBB BH)

Praça da Liberdade, 450 - Funcionários, Belo Horizonte - MG

Detalhes

A Galeria Zipper, em São Paulo, recebe a 17ª edição do Salão dos Artistas Sem Galeria, promovido pelo portal Mapa das Artes. A exposição com obras de onze artistas, dez

Detalhes

A Galeria Zipper, em São Paulo, recebe a 17ª edição do Salão dos Artistas Sem Galeria, promovido pelo portal Mapa das Artes. A exposição com obras de onze artistas, dez que foram selecionados e ainda o contemplado com o Prêmio Estímulo Fora do Eixo. Este ano foram 371 inscrições, o que representa um aumento de 22% no número inscrições recebidas para a mostra de 2025.

Nesta edição, foram selecionados Bernardo Liu (RJ), Dani Shirozono (MG/SP), Demir (DF), Isabela Vatavuk (SP), Mariana Riera (RS), Paulo Valeriano (DF), Rafael Santacosta (SP), Romildo Rocha (MA), Shay Marias (RJ/SP) e Timóteo Lopes (BA).

O Salão concedeu, ainda este ano, o Prêmio Estímulo Fora do Eixo, no valor de R$ 1.000,00, direcionado a um artista não selecionado e residente fora do eixo Rio-São Paulo. O premiado foi Pedro Kubitschek (MG). O júri de seleção foi formado pelo produtor e curador independente Alef Bazilio; pelo artista, curador e professor universitário Diogo Santos Bessa e pelo jornalista, crítico e curador independente Mario Gioia. Ao final da exposição, três entre os artistas selecionados serão premiados com valores de R$ 3 mil, R$ 2 mil e R$ 1 mil.

O Salão dos Artistas Sem Galeria tem como objetivo movimentar e estimular o circuito de arte logo no início do ano. Há 17 anos o evento avalia, exibe, documenta e divulga a produção de artistas plásticos que não tenham contratos verbais ou formais (representação) com qualquer galeria de arte na cidade de São Paulo. O Salão abre o calendário de artes em São Paulo e é uma porta de entrada para esses artistas no concorrido circuito comercial das artes no país.

O Salão dos Artistas Sem Galeria tem concepção e organização de Celso Fioravante, assistência de Lucas Malkut e projeto gráfico de Cláudia Gil (Estúdio Ponto).

Artistas selecionados na 17ª edição (por ordem de inscrição)

Timóteo Lopes – BA: @timoteolopes_

Mariana Riera – RS: @marianariera82

Romildo Rocha – MA: @rocha.abencoado

Isabela Vatavuk – SP: @isabelavatavuk

Rafael Santacosta – SP: @santacosta.art

Paulo Valeriano – DF: @paulovalerianopaulovaleriano

Shay Marias – RJ/SP: @shaymarias

Dani Shirozono – MG/SP: @danishirozono

Demir – DF: @demirartesplastica

Bernardo Liu – RJ: @bernardoliu

Pedro Kubitschek – MG (Prêmio Estímulo Fora do Eixo): @pedrodinizkubitschek

Serviço

Exposição coletiva | 17º Salão dos Artistas sem Galeria

De 17 de janeiro a 28 de fevereiro

Segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h, sábados, das 11h ás 17h

Período

Local

Zipper Galeria

R. Estados Unidos, 1494 Jardim America 01427-001 São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

Em sua prática, a artista franco-brasileira Julia Kater investiga a relação entre a paisagem, a cor e a superfície. Ela transita pela fotografia e pela colagem, concentrando-se na construção da

Detalhes

Em sua prática, a artista franco-brasileira Julia Kater investiga a relação entre a paisagem, a cor e a superfície. Ela transita pela fotografia e pela colagem, concentrando-se na construção da imagem por meio do recorte e da justaposição. Na fotografia, Kater parte do entendimento de que toda imagem é, por definição, um fragmento – um enquadramento que recorta e isola uma parte da cena. Em sua obra, a imagem não é apenas um registro de um instante, mas sim, resultado de um deslocamento – algo que se desfaz e se recompõe do mesmo gesto. As imagens, muitas vezes próximas, não buscam documentar, mas construir um novo campo de sentido. Nas colagens, o gesto do recorte ganha corpo. Fragmentos de fotografias são manualmente cortados, sobrepostos e organizados em camadas que criam passagens visuais marcadas por transições sutis de cor. Esses acúmulos evocam variações de luz, atmosferas e a própria passagem do tempo através de gradações cromáticas.

Na individual Duplo, Julia Kater apresenta trabalhos recentes, desenvolvidos a partir da pesquisa realizada durante sua residência artística em Paris. “Minha pesquisa se concentra na paisagem e na forma como a cor participa da construção da imagem – ora como elemento acrescentado à fotografia, ora como algo que emerge da própria superfície. Nas colagens, a paisagem é construída por recortes, justaposições e gradações de cor. Já nos trabalhos em tecido, a cor atua a partir da própria superfície, por meio do tingimento manual, atravessando a fotografia impressa. Esses procedimentos aprofundam a minha investigação sobre a relação entre a paisagem, a cor e a superfície”, explica a artista.

Em destaque, duas obras que serão exibidas na mostra: uma em tecido que faz parte da nova série e um díptico inédito. Corpo de Pedra (Centauro), 2025, impressão digital pigmentária sobre seda tingida à mão com tintas a base de plantas e, Sem Título, 2025, colagem com impressão em pigmento mineral sobre papel matt Hahnemüle 210g, díptico com dimensão de 167 x 144 cm cada.

A artista comenta: “dou continuidade às colagens feitas a partir do recorte de fotografia impressa em papel algodão e passo a trabalhar com a seda também como suporte. O processo envolve o tingimento manual do tecido com plantas naturais, como o índigo, seguido da impressão da imagem fotográfica. Esse procedimento me interessa por sua proximidade com o processo fotográfico analógico, sobretudo a noção de banho, de tempo de imersão e de fixação da cor na superfície”. Todas as obras foram produzidas especialmente para a exposição, que fica em cartaz até 07 de março de 2026.

Serviço

Exposição | Julia Kater: Duplo

De 22 de janeiro a 07 de março

Segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h; sábado, das 10h às 15h

Período

Local

Simões de Assis

Al. Lorena, 2050 A, Jardins - São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A Galatea tem o prazer de apresentar Guilherme Gallé: entre a pintura e a pintura, primeira individual do artista paulistano Guilherme Gallé (1994, São Paulo), na unidade da galeria na

Detalhes

A Galatea tem o prazer de apresentar Guilherme Gallé: entre a pintura e a pintura, primeira individual do artista paulistano Guilherme Gallé (1994, São Paulo), na unidade da galeria na rua Padre João Manuel. A mostra reúne mais de 20 pinturas inéditas, realizadas em 2025, e conta com texto crítico do curador e crítico de arte Tadeu Chiarelli e com texto de apresentação do crítico de arte Rodrigo Naves.

A exposição apresenta um conjunto no qual Gallé revela um processo contínuo de depuração: um quadro aciona o seguinte, num movimento em que cor, forma e espaço se reorganizam respondendo uns aos outros. Situadas no limiar entre abstração e sugestão figurativa, suas composições, sempre sem título, convidam à lenta contemplação, dando espaço para que o olhar oscile entre a atenção ao detalhe e ao conjunto.

Partindo sempre de um “lugar” ou pretexto de realidade, como paisagens ou naturezas-mortas, mas sem recorrer ao ponto de fuga renascentista, Gallé mantém a superfície pictórica deliberadamente plana. As cores tonais, construídas em camadas, estruturam o plano com uma matéria espessa, marcado por incisões, apagamentos e pentimentos, que dão indícios do processo da pintura ao mesmo tempo que o impulsionam.

Entre as exposições das quais Guilherme participou ao longo de sua trajetória, destacam-se: Joaquín Torres García – 150 anos, (Coletiva, Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil – CCBB, São Paulo / Brasília / Belo Horizonte, 2025–2026); Ponto de mutação (Coletiva, Almeida & Dale, São Paulo, 2025); O silêncio da tradição: pinturas contemporâneas (Coletiva, Centro Cultural Maria Antonia, São Paulo, 2025); Para falar de amor (Coletiva, Noviciado Nossa Senhora das Graças Irmãs Salesianas, São Paulo, 2024); 18º Território da Arte de Araraquara (2021); Arte invisível (Coletiva, Oficina Cultural Oswald de Andrade, São Paulo, 2019); e Luiz Sacilotto, o gesto da razão (Coletiva, Centro Cultural do Alumínio, São Paulo, 2018).

Serviço

Exposição | Guilherme Gallé: entre a pintura e a pintura

De 22 de janeiro a 07 de março

Segunda a quinta, das 10 às 19h, sexta, das 10 às 18h, Sábado, das 11h às 17h

Período

Local

Galatea Padre João Manuel

R. Padre João Manuel, 808, Jardins – São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A artista Luiza Sigulem inaugura sua segunda exposição individual, Manual para percorrer a menor distância de um ponto a outro, com abertura marcada para o dia 24 de janeiro de 2026, no Ateliê397, em

Detalhes

A artista Luiza Sigulem inaugura sua segunda exposição individual, Manual para percorrer a menor distância de um ponto a outro, com abertura marcada para o dia 24 de janeiro de 2026, no Ateliê397, em São Paulo. Reunindo um conjunto inédito de trabalhos, a mostra, com curadoria de Juliana Caffé, tensiona a relação entre corpo, arquitetura e o tempo, propondo o deslocamento como uma operação de ajuste e reflexão crítica.

O projeto toma a instabilidade como condição que reorganiza a relação entre corpo e arquitetura, produzindo um tempo que não coincide com a lógica da eficiência. Em sintonia com a teoria Crip (termo reapropriado de cripple que nomeia práticas que deslocam o “corpo padrão”) e o conceito de crip time — uma temporalidade que acolhe pausas, ritmos variáveis e o não-alinhamento com o relógio produtivista —, o trabalho de Sigulem afirma a diferença não como exceção, mas como método.

“Ao longo do meu processo, a falta de acessibilidade se manifestou no tempo necessário para lidar com pequenos e grandes obstáculos e na atenção exigida por ajustes mínimos que se acumularam de forma quase imperceptível,” declara a artista. “Essa experiência deslocou a ideia de eficiência e aproximou minha produção de uma noção de tempo expandido, no qual o ritmo do corpo não coincide com a expectativa normativa da reprodução capitalista. É nesse descompasso que o meu trabalho se constrói.”

O projeto, que incorpora pela primeira vez vídeo-performances, intervenções e uma escultura em diálogo com a fotografia, marca um momento de expansão na trajetória da artista e coloca a acessibilidade no centro da construção estética e poética. Também tensiona a invisibilidade de uma parcela expressiva da população: segundo dados da PNAD Contínua 2022 (IBGE), o Brasil possui cerca de 18,6 milhões de pessoas com deficiência, das quais aproximadamente 3,4 milhões apresentam deficiência física nos membros inferiores, contingente que enfrenta diariamente as barreiras arquitetônicas discutidas na mostra.

Arquitetura e poética: uma inversão expositiva

O projeto nasce de um dado incontornável do contexto paulistano: a dificuldade estrutural de encontrar espaços expositivos capazes de acolher a investigação da artista de forma coerente com suas questões. Diante da inexistência de alternativas viáveis e dos prazos institucionais, a mostra abraçou esse limite como parte do projeto, transformando-o em campo de reflexão.

“A escolha do Ateliê397 como sede da exposição responde a esse contexto. Enquanto espaço independente, ele oferece uma abertura conceitual e um campo real de negociação para a construção deste projeto,” comenta a curadora Juliana Caffé. “Situado na Travessa Dona Paula, em uma área marcada por importantes equipamentos culturais igualmente limitados em termos de acessibilidade, o espaço é incorporado pela exposição como elemento ativo, deixando de operar como suporte neutro para integrar arquitetura, circulação e entorno ao campo de discussão proposto.”

Diante dos limites arquitetônicos do Ateliê, Sigulem não trata a falta de acessibilidade como obstáculo a ser corrigido, mas como condição a ser trabalhada criticamente. A expografia opera uma inversão deliberada: em vez de adaptar o espaço a um padrão normativo, é o público que se vê levado a recalibrar seu corpo diante de passagens reduzidas e escalas deslocadas.

Nesse sentido, a mostra apresenta uma instalação, desenvolvida pela artista em colaboração com a dupla de arquitetos Francisco Rivas e Rodrigo Messina, que reúne dispositivos de acessibilidade e permanência pensados como parte constitutiva da obra. A intervenção reorganiza a recepção: a porta e o batente foram deslocados para permitir abertura total (180°); bancos e banquinhos foram distribuídos para acolher o repouso; e almofadas nos bancos externos estendem a experiência para o entorno.

A radicalidade da proposta reflete-se na ocupação institucional: a lateral da escada, que conduz a um segundo andar inacessível para pessoas com deficiência, foi convertida em uma pequena biblioteca de teoria Crip. “Durante a mostra, o Ateliê397 aceitou tornar o andar superior inoperável, suspendendo seu uso como sala de projeção para tornar explícito o limite arquitetônico em vez de ocultá-lo. E, como desdobramento externo, o projeto inclui a produção e doação de rampas móveis sob medida para espaços culturais vizinhos na vila, provocando o circuito a pensar coletivamente suas condições de acesso”, pontua Caffé.

O projeto se alinha a debates contemporâneos que buscam a visibilidade sem captura, onde o trabalho opera por sensação, ritmo e microeventos corporais que não se reduzem a uma imagem “explicativa” ou a um conteúdo de fácil consumo. Trata-se de uma abordagem que reconhece o acesso como estética e a deficiência como um diagnóstico do espaço e das normas. Dessa forma, curadoria e expografia tornam-se parte ativa do trabalho. Textos em Braille, audiodescrição e fototátil acompanham a exposição, cujo funcionamento e mediação incorporam a contratação de pessoas PcD, respeitando diferentes tempos de circulação.

Além disso, todos os dispositivos da mostra foram realizados com materiais simples e de baixo custo, afirmando a possibilidade de construir formas de acolhimento mesmo em arquiteturas que não atendem plenamente às normas legais.

Corpo em negociação: vídeo, escultura e fotografia

Se em trabalhos anteriores Sigulem convidava o outro a se ajustar a determinadas escalas, a exemplo da série Jeito de Corpo (2024), nesta individual a artista coloca o próprio corpo no centro da experiência. Diferentes obras exploram esse deslocamento de perspectiva, ora propondo situações em que o público é levado a reorientar sua percepção espacial, ora acompanhando a artista em gestos de negociação contínua com o espaço.

Os vídeos partem de releituras de performances históricas, realizadas a partir do corpo da artista e atravessadas por questões de gênero e potência. As ações não buscam fidelidade ao gesto original, mas operam como tradução situada, na qual cada movimento carrega a marca de um ajuste necessário. A câmera acompanha o processo sem corrigir o desvio, permitindo que a falha e o esforço permaneçam visíveis.

É o caso da série inédita Rampas (2025), um conjunto de vinte fotografias derivadas do vídeo-performance Painting (Retoque) (a partir de Francis Alÿs). No vídeo, a artista marca com tinta amarela pontos das ruas de São Paulo onde deveriam existir rampas de acesso, evidenciando ausências de acessibilidade na paisagem urbana. As fotografias isolam esses gestos e vestígios, transformando a ação performática em imagens que registram a fricção entre corpo, cidade e infraestrutura.

Ao adotar como referência a altura do campo visual de uma pessoa cadeirante, a exposição desloca a escala normativa do espaço expositivo e introduz um regime de percepção em que o corpo não se ajusta à arquitetura, mas a arquitetura se torna índice de seus limites.

Uma escultura pontua o espaço, testando limites entre função e falha e questionando estruturas pensadas para orientar o movimento. Em uma instalação, um vídeo dedicado à imagem da queda articula sua repetição como experiência física e simbólica. Em conjunto, as obras sugerem que toda trajetória é atravessada por desvios, pausas e negociações, e que a menor distância entre dois pontos, raramente se apresenta como linha reta.

A exposição Manual para percorrer a menor distância de um ponto a outro integra o projeto Jeito de Corpo, contemplado no EDITAL FOMENTO CULTSP PNAB Nº 25/2024, da Secretaria da Cultura, Economia e Indústria Criativas, Estado de São Paulo.

Serviço

Exposição | Manual para percorrer a menor distância de um ponto a outro

De 24 de janeiro a 28 de fevereiro

Quarta a sábado, das 14h às 18h

Período

Local

Ateliê397

Travessa Dona Paula, 119A – Higienópolis, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A Galeria Alma da Rua, localizada em um dos endereços mais emblemáticos da capital paulista, o Beco do Batman, abre em 24 de janeiro a mostra “Onírica” de Kelly S.

Detalhes

A Galeria Alma da Rua, localizada em um dos endereços mais emblemáticos da capital paulista, o Beco do Batman, abre em 24 de janeiro a mostra “Onírica” de Kelly S. Reis em que apresenta dezenas de obras, todas inéditas, com foco no universo simbólico e surreal da artista, que é afro-indígena. Sua produção investiga o hibridismo e os entrelaçamentos culturais e biológicos a partir de um olhar feminino, tendo a miscigenação como eixo central.

O onirismo manifesta-se como um campo sensível ligado aos sonhos, à imaginação, à intuição e ao inconsciente. Nesse território, a mulher negra assume o protagonismo e estabelece uma relação simbiótica com a natureza. Por meio da representação de mulheres afro-indígenas e do uso de uma linguagem simbólica em cenários etéreos, a artista evoca questões concretas, propondo uma reflexão poética sobre ancestralidade, pertencimento e identidade.

As figuras femininas presentes nas obras de Kelly afastam-se de narrativas estereotipadas de vitimização e sofrimento. Assim, Kelly S. Reis constrói imagens de mulheres negras como potência – corpos que afirmam força, presença e imponência.

Serviço

Exposição | Onírica

De 25 de janeiro a 19 de fevereiro

Todos os dias das 10h às 18h

Período

Local

Galeria Alma da Rua

Rua Gonçalo Afonso 96 Beco do Batman, Vila Madalena, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

O Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (MAM Rio) recebe, em janeiro de 2026, a primeira edição brasileira de Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile (Vela/Tela – Tela/Vela), projeto seminal do

Detalhes

O Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (MAM Rio) recebe, em janeiro de 2026, a primeira edição brasileira de Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile (Vela/Tela – Tela/Vela), projeto seminal do artista Daniel Buren (1938, Boulogne-Billancourt), realizado em parceria com a Galeria Nara Roesler. Iniciado em 1975, o trabalho transforma velas de barcos em suportes de arte, deslocando o olhar do espectador e ativando o espaço ao redor por meio do movimento, da cor e da forma. Ao longo de cinco décadas, o projeto foi apresentado em cidades como Genebra, Lucerna, Miami e Minneapolis, sempre em diálogo direto com a paisagem e o contexto locais.

Concebida originalmente em Berlim, em 1975, Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile destaca o uso das listras verticais que Daniel Buren define como sua “ferramenta visual”. O próprio título da obra explicita o deslocamento proposto pelo artista ao articular dois campos centrais do modernismo do século 20 — a pintura abstrata e o readymade —, transformando velas de barcos em pinturas e ampliando o campo de ação da obra para além do espaço expositivo.

“Trata-se de um trabalho feito ao ar livre e que conta com fatores externos e imprevisíveis, como clima, vento, visibilidade e posicionamento das velas e barcos, de modo que, ainda que tenha sido uma ação realizada dezenas de vezes, ela nunca é idêntica, tal qual uma peça de teatro ou um ato dramático”, disse Daniel Buren, em conversa com Pavel Pyś, curador do Walker Art Center de Minneapolis, publicada pelo museu em 2018.

No dia 24 de janeiro, a ação tem início com uma regata-performance na Baía de Guanabara. Onze veleiros da classe Optimist partem da Marina da Glória e percorrem o trajeto até a Praia do Flamengo, equipados com velas que incorporam as listras verticais brancas e coloridas criadas por Buren. Em movimento, as velas se convertem em intervenções artísticas vivas, ativando o espaço marítimo e o cenário do Rio como parte constitutiva da obra. O público poderá acompanhar a ação desde a orla, e toda a performance será registrada.

Após a conclusão da regata, as velas serão deslocadas para o foyer do MAM Rio, onde passarão a integrar a exposição derivada da regata, em cartaz de 28 de janeiro a 12 de abril de 2026. Instaladas em estruturas autoportantes, as onze velas – com 2,68 m de altura (2,98 m com a base) – serão dispostas no espaço de acordo com a ordem de chegada da regata, seguindo o protocolo estabelecido por Buren desde as primeiras edições do projeto. O procedimento preserva o vínculo direto entre a performance e a exposição, e evidencia a transformação das velas de objetos utilitários em objetos artísticos. A expografia é assinada pela arquiteta Sol Camacho.

“Desde os anos 1960, Buren desenvolve uma reflexão crítica sobre o espaço e as instituições, sendo um dos pioneiros da arte in situ e da arte conceitual. Embora Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile tenha circulado por diversos países ao longo dos últimos 50 anos, esta é a primeira vez que a obra é apresentada no Brasil. A proximidade do MAM Rio com a Baía de Guanabara, sua história na experimentação e sua arquitetura integrada ao entorno fazem do museu um espaço particularmente privilegiado para a obra do artista”, comenta Yole Mendonça, diretora executiva do MAM Rio.

Ao prolongar no museu uma experiência iniciada no mar, Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile estabelece uma continuidade entre a ação na Baía de Guanabara e sua apresentação no espaço expositivo do MAM Rio, integrando paisagem, arquitetura e percurso em uma mesma experiência artística.

“A maneira como Buren tensiona a relação da arte com espaços específicos, principalmente com os espaços públicos, é fundamental para entender a história da arte contemporânea. E essa peça Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile, que começa na Baía de Guanabara e que chega aos espaços internos do museu, é um exemplo perfeito dessa prática”, comenta Pablo Lafuente, diretor artístico do MAM Rio.

Em continuidade ao projeto, a Nara Roesler Books publicará uma edição dedicada à presença de Daniel Buren no Brasil, reunindo ensaios críticos e documentos da realização de Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile no Rio de Janeiro, em 2026.

Serviço

Exposição | Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile (Vela/Tela – Tela/Vela)

De 28 de janeiro a 12 de abril

Quartas, quintas, sextas, sábados domingos e feriados, das 10h às 18h

Período

Detalhes

Galatea e Nara Roesler têm a alegria de colaborar pela primeira vez na realização da mostra Barracas e fachadas do nordeste, Com curadoria de Tomás Toledo, sócio-fundador da Galatea e Alana

Detalhes

Galatea e Nara Roesler têm a alegria de colaborar pela primeira vez na realização da mostra Barracas e fachadas do nordeste,

Com curadoria de Tomás Toledo, sócio-fundador da Galatea e Alana Silveira, diretora da Galatea Salvador, a coletiva propõe uma interlocução entre os programas das galerias ao explorar as afinidades entre os artistas Montez Magno (1934, Pernambuco), Mari Ra (1996, São Paulo), Zé di Cabeça (1974, Bahia), Fabio Miguez (1962, São Paulo) e Adenor Gondim (1950, Bahia). A mostra propõe um olhar ampliado para as arquiteturas vernaculares que marcam o Nordeste: fachadas urbanas, platibandas ornamentais, barracas de feiras e festas e estruturas efêmeras que configuram a paisagem social e cultural da região.

Nesse conjunto, Fabio Miguez investiga as fachadas de Salvador como um mosaico de variações arquitetônicas enquanto Zé di Cabeça transforma registros das platibandas do subúrbio ferroviário soteropolitano em pinturas. Mari Ra reconhece afinidades entre as geometrias que encontrou em Recife e Olinda e aquelas presentes na Zona Leste paulistana, revelando vínculos construídos pela migração nordestina. Já Montez Magno e Adenor Gondim convergem ao destacar as formas vernaculares do Nordeste, Magno pela via da abstração geométrica presentes nas séries Barracas do Nordeste (1972-1993) e Fachadas do Nordeste (1996-1997) e Gondim pelo registro fotográfico das barracas que marcaram as festas populares de Salvador.

A parceria entre as galerias se dá no aniversário de 2 anos da Galatea em Salvador e reforça o seu intuito de fazer da sede na capital baiana um ponto de convergência para intercâmbios e trocas entre artistas, agentes culturais, colecionadores, galerias e o público em geral.

Serviço

Exposição | Barracas e fachadas do nordeste

De 30 de janeiro a 30 de maio

Terça – quinta, das 10 às 19h, sexta, das 10 às 18h, sábado, das 11h às 15h

Período

Local

Galeria Galatea Salvador

R. Chile, 22 - Centro, Salvador - BA

Detalhes

A Pinacoteca de São Bernardo do Campo apresenta, entre os dias 31 de janeiro e 28 de março de 2026, uma exposição individual do artista Daniel Melim (São Bernardo do Campo, SP – 1979). Com curadoria assinada pelo

Detalhes

A Pinacoteca de São Bernardo do Campo apresenta, entre os dias 31 de janeiro e 28 de março de 2026, uma exposição individual do artista Daniel Melim (São Bernardo do Campo, SP – 1979). Com curadoria assinada pelo pesquisador e especialista em arte pública Baixo Ribeiro e produção da Paradoxa Cultural, a mostra Reflexos Urbanos: a arte de Daniel Melim reúne um conjunto de 12 obras – dentre elas oito trabalhos inéditos.

A exposição apresenta uma verdadeira introspectiva do trabalho de Daniel Melim – um mergulho em seu processo criativo a partir do olhar de dentro do ateliê. Ao lado de obras que marcaram sua trajetória, o público encontrará trabalhos inéditos que apontam novos caminhos em sua produção. Entre os destaques, uma pintura em grande formato — 2,5m x 12m — e um mural coletivo que será produzido ao longo da mostra.

Com obras em diferentes formatos e dimensões – pinturas em telas, relevos, instalação, cadernos, elementos do ateliê do artista -, a mostra aborda o papel da arte urbana na construção de identidades coletivas, a ocupação simbólica dos espaços públicos e o desafio de trazer essas linguagens para o contexto institucional, sem perder seu caráter de diálogo com a comunidade.

O recorte proposto pela curadoria de Baixo Ribeiro conecta passado e presente, mas principalmente, evidencia como Melim transforma referências visuais do cotidiano em obras que geram reflexão crítica, possibilitando criar pontes entre o espaço público e o institucional.

A expografia de “Reflexos Urbanos: a arte de Daniel Melim” foi pensada como um ateliê expandido, com o intuito de aproximar o público do processo criativo de Melim. Dentro do espaço expositivo, haverá um mural colaborativo, no qual os visitantes poderão experimentar técnicas como stencil e lambe-lambe. Essa iniciativa integra a proposta educativa da mostra e transforma o visitante em coautor, fortalecendo a relação entre público e obra.

“Sempre me interessei pela relação entre a arte e o espaço urbano. O stencil foi minha primeira linguagem e continua sendo o ponto de partida para criar narrativas visuais que dialogam com a vida cotidiana. Essa mostra é sobre esse diálogo: cidade, obra e público”, explica Daniel Melim.

Artista visual e educador, reconhecido como um dos principais nomes da arte urbana brasileira, Daniel Melim iniciou sua trajetória artística no final dos anos 1990 com grafite e stencil nas ruas do ABC Paulista. Desenvolve uma pesquisa autoral sobre o stencil como meio expressivo, resgatando sua importância histórica na formação da street art no Brasil e expandindo seus potenciais pictóricos para além do espaço público. Sua produção se caracteriza pelo diálogo entre obra, arquitetura e cidade, frequentemente instalada em áreas em processo de transformação urbana.

“Essa exposição individual é uma forma de me reconectar com o lugar onde tudo começou. São Bernardo do Campo foi minha primeira escola de arte – não apenas pela faculdade, mas pela rua, pelos muros, pelas greves que eu vi quando ainda era criança. Essa experiência formou a minha visão de mundo. Trazer esse trabalho de volta, no espaço da Pinacoteca, é como abrir o meu ateliê para a cidade que tanto me acolheu e me fez crescer”, comenta.

Os stencils, o imaginário gráfico da publicidade, críticas à sociedade de consumo e ao cotidiano urbano são marcas do trabalho de Melim. Cores chapadas, sobreposições e composições equilibradas são algumas das características que aparecem tanto nas obras históricas de Daniel Melim, quanto em novos trabalhos que o artista está produzindo para a individual. “Reflexos Urbanos: a arte de Daniel Melim” é um convite para o visitante mergulhar e se aproximar do processo criativo do artista. A mostra fica em cartaz até o dia 28 de março de 2026.

A exposição “Reflexos Urbanos: a arte de Daniel Melim” é realizada com apoio da Política Nacional Aldir Blanc de Fomento à Cultura (PNAB); do Programa de Ação Cultural – ProAC, da Secretaria da Cultura, Economia e Indústria Criativas do Governo do Estado de São Paulo; do Ministério da Cultura e do Governo Federal.

Serviço

Exposição | Reflexos Urbanos: a arte de Daniel Melim

De 31 de janeiro e 28 de março

Terça, das 9h às 20h; quarta a sexta, das 9h às 17h; sábado, das 10h às 16h

Período

Local

Pinacoteca de São Bernardo do Campo

Rua Kara, nº 105 - Jardim do Mar - São Bernardo do Campo - SP

Detalhes

A Luciana Brito Galeria abre sua programação de 2026 com a exposição Ainda Bem, Atravessei as Nuvens, a segunda da artista Gabriela Machado na galeria. A mostra destaca pinturas inéditas

Detalhes

A Luciana Brito Galeria abre sua programação de 2026 com a exposição Ainda Bem, Atravessei as Nuvens, a segunda da artista Gabriela Machado na galeria. A mostra destaca pinturas inéditas de maior dimensão – em diálogo com outras menores – realizadas entre 2024 e 2026, ocupando todo o espaço do Pavilhão. O texto crítico é assinado por Amanda Abi Khalil.

As crônicas do cotidiano, os cenários reais e oníricos, a temperatura e o brilho das cores, as sensações do dia a dia. Nada escapa ao crivo de um imaginário sensível que orienta o olhar de Gabriela Machado. A artista seleciona aquilo que lhe é mais atraente e o traduz para a linguagem pictórica. Neste conjunto de pinturas inéditas, produzidas nos últimos anos, ela articula fragmentos de histórias e memórias, além de cenas de paisagens captadas em viagens. Esses pequenos acontecimentos, cenas ou observações da vida, embora banais à primeira vista, ganham sentido, densidade e poesia quando reinterpretados pela artista.

Diferentemente de sua primeira exposição na galeria, realizada em 2024, as pinturas de Ainda Bem, Atravessei as Nuvens apresentam-se agora mais figurativas, revelando um jogo híbrido que articula não apenas a percepção imediata daquilo que o olhar alcança, mas também o imaginário e a memória da artista. O universo fantástico circense, por exemplo, surge em diversas obras, como Marambaia (2026) e Ainda Bem, Atravessei as Nuvens (2026), nas quais a figura do leão é retratada a partir de um repertório infantil compartilhado por sua geração.

Em outras pinturas de menor formato, aparecem paisagens que conjugam céu, vegetação e mar, assim como retratos de objetos e esculturas. Em todas elas, contudo, a artista enfatiza a luminosidade e o brilho, elementos que se impõem de imediato ao olhar do espectador e traduzem uma atmosfera de leveza e mistério deliberadamente construída. Já nas obras Largo do Machado (2026), Luzinhas (2014–2025) e Veronese (2013–2025), as luzes de Natal assumem o papel de protagonistas. Segundo explica a artista, o efeito luminoso é produzido deliberadamente durante o processo de produção: em uma primeira etapa ela trabalha com a tinta acrílica, para então finalizar com a tinta a óleo.

O fundo rosa observado em algumas pinturas, como em Ginger (2026), foi inspirado na tonalidade dos tapumes dos canteiros de obra. Outro detalhe também relevante é a moldura reproduzida pela artista em alguns trabalhos de menor formato, funcionando como uma extensão da pintura e contribuindo para a construção de uma maior profundidade espacial.

Serviço

Exposição | Ainda Bem, Atravessei as Nuvens

De 05 de fevereiro a 21 de março

Segunda, das 10h às 18h, terça a sexta, das 10h às 19h, sábado, das 11h às 17h

Período

Detalhes

A Gomide&Co tem o prazer de apresentar ANTONIO DIAS / IMAGE + MIRAGE, primeira individual de Antonio Dias (1944–2018) na galeria. Organizada em parceria com a Sprovieri, Londres, a partir de obras do artista preservadas

Detalhes

A Gomide&Co tem o prazer de apresentar ANTONIO DIAS / IMAGE + MIRAGE, primeira individual de Antonio Dias (1944–2018) na galeria. Organizada em parceria com a Sprovieri, Londres, a partir de obras do artista preservadas por Gió Marconi, a exposição tem organização e texto crítico de Gustavo Motta e expografia de Deyson Gilbert.

A abertura acontece no dia 10 de fevereiro (terça-feira), às 18h, e a exposição segue em cartaz até 21 de março. Entre as obras em exibição, a exposição destaca sete pinturas pertencentes à Gió Marconi realizadas por Antonio Dias entre 1968 e 71, em seus anos iniciais em Milão, demarcando um momento importante na trajetória do artista.

No dia 14 de março (sábado), às 11h, haverá o lançamento de uma publicação que acompanha a mostra. Também com organização e texto de Gustavo Motta, a publicação apresenta o conjunto completo de obras do artista sob a guarda de Gió Marconi, além de documentação complementar sobre seu período de execução. Na ocasião do lançamento, haverá uma mesa redonda com a presença de Gustavo Motta, Sergio Martins e Lara Cristina Casares Rivetti. A mediação será de Deyson Gilbert.

Nascido em Campina Grande (PB) em 1944, Antonio Dias mudou-se com a família para o Rio de Janeiro em 1957, onde iniciou sua carreira artística destacando-se com uma produção que logo foi associada à Pop Arte e à Nova Figuração. Em meados da década de 1960, o artista deixou o Brasil – em um contexto marcado pela Ditadura Militar – e seguiu para Paris, após receber uma bolsa do governo francês por sua participação na 4ª Bienal de Paris. Na Europa, o trabalho de Dias passou a apresentar uma configuração mais conceitual, chamando a atenção do galerista Giorgio Marconi (1930–2024), fundador do Studio Marconi (1965–1992) – espaço que desde seu início foi referência para a arte contemporânea de Milão.

Sob a representação da galeria, Dias decidiu fixar-se na cidade, onde manteve uma de suas residências até o final de sua vida. Lá, estabeleceu estreitas relações com artistas como Mario Schifano, Luciano Fabro, Alighiero Boetti e Giulio Paolini. As obras desse período, apresentadas na exposição, refletem a consolidação da linguagem conceitual do artista em seus primeiros anos na Europa, marcada pela precisão formal, com superfícies austeras combinadas a palavras, frases ou diagramas que operam como comentários autorreflexivos sobre o fazer artístico como atividade mental. O período antecipa – e em parte coincide – com a produção da série The Illustration of Art (1971–78), considerada uma das mais emblemáticas do artista.

As obras realizadas por Dias em Milão sintetizam uma virada decisiva na trajetória do artista, na qual a pintura se torna simultaneamente mais sóbria e mais reflexiva. Por meio de grandes campos monocromáticos, palavras isoladas e estruturas rigorosamente diagramadas, o artista reduz a imagem ao essencial e transforma o quadro em um espaço de pensamento. Conforme Motta esclarece, o que se vê é menos importante do que o que falta: a pintura passa a operar como um dispositivo aberto, que convoca o espectador a completar sentidos e a produzir imagens mentais. Ao incorporar procedimentos gráficos oriundos do design e da comunicação de massa, Dias desloca a pintura do terreno da representação para o da problematização, articulando, nas palavras do artista, uma “arte negativa” que reflete sobre o próprio estatuto da imagem e sobre o fazer artístico como atividade intelectual. Nesse conjunto, consolida-se uma linguagem em que a obra não oferece respostas, mas se apresenta como campo de tensão entre palavra, superfície e imaginação.

A mostra em São Paulo dá sequência à exposição apresentada pela Sprovieri, em Londres, em outubro de 2025, composta por obras do mesmo período – todas pertencentes à Gió Marconi, filho de Giorgio. À frente da Galleria Gió Marconi desde 1990, após ter trabalhado com o pai no espaço experimental para jovens artistas chamado Studio Marconi 17 (1987–1990), Gió também é responsável pela Fondazioni Marconi, fundada em 2004 com o propósito de dar sequência ao legado do antigo Studio Marconi.

Entre as obras apresentadas na exposição da Gomide&Co, figuram pinturas que estiveram presentes na individual inaugural de Antonio Dias no Studio Marconi, em 1969, que contou com texto crítico de Tommaso Trini, além da mais recente dedicada ao artista pela fundação, Antonio Dias – Una collezione, 1968–1976 (2017). A seleção também compreende obras que estiveram em outras ocasiões importantes da carreira do artista, como a histórica (e polêmica) Guggenheim International Exhibition de 1971 e a 34ª Bienal de São Paulo (2021).

A exposição na Gomide&Co também se destaca por oferecer um olhar mais contemporâneo para os primeiros anos de Dias em Milão. A galeria reuniu uma equipe jovem de renome no sentido de atualizar as perspectivas sobre a produção do artista no período. A começar pela organização, sob responsabilidade de Gustavo Motta, considerado atualmente um dos intelectuais da nova geração mais reconhecidos quando se trata de Antonio Dias, tendo assinado a curadoria de Antonio Dias / Arquivo / O Lugar do Trabalho no Instituto de Arte Contemporânea (IAC) em 2021, exposição baseada no acervo documental do artista pertencente à instituição. O projeto expográfico é do artista Deyson Gilbert, que foi responsável pela expografia da mostra curada por Motta no IAC. No caso da exposição na galeria, a proposta de Gilbert anseia refletir e dar continuidade ao processo estético próprio da produção de Dias no período.

Além das obras, a exposição apresenta também uma seleção inédita de documentos do Fundo Antonio Dias do acervo do IAC, com materiais que ainda não estavam disponíveis na instituição na época da exposição de 2021. Complementa a equipe o estúdio M-CAU, da artista Maria Cau Levy, responsável pelo projeto gráfico da publicação.

Reunindo obras históricas, documentação inédita e uma equipe que dialoga diretamente com o legado crítico de Antonio Dias, a exposição reafirma a atualidade e a complexidade da produção do artista no contexto internacional. ANTONIO DIAS / IMAGE + MIRAGE propõe não apenas uma revisão de um momento decisivo da trajetória de Dias, mas também uma leitura renovada de sua contribuição para a arte conceitual, evidenciando como as questões formuladas pelo artista no final dos anos 1960 seguem ressoando de maneira incisiva no debate contemporâneo.

Serviço

Exposição | ANTONIO DIAS / IMAGE + MIRAGE

De 10 de fevereiro a 21 de março

Segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h; sábados, das 11h às 17h

Período

Local

Gomide & Co

Avenida Paulista, 2644 01310-300 - São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

Prestes a completar 95 anos, Augusto de Campos publicou recentemente o livro “pós poemas” (2025), que reúne um conjunto de trabalhos, compreendido como um marco de síntese da evolução de

Detalhes

Prestes a completar 95 anos, Augusto de Campos publicou recentemente o livro “pós poemas” (2025), que reúne um conjunto de trabalhos, compreendido como um marco de síntese da evolução de sua pesquisa poética. Produzidas ao longo das últimas duas décadas, as obras reunidas no volume deram origem a uma seleção transposta para o espaço da Sala Modernista da galeria, propondo uma experiência não apenas visual, mas também espacial, em diálogo com o ambiente projetado por Rino Levi. No contexto da exposição, os poemas deixam de ser apenas objetos de leitura para se afirmarem como experiências visuais e espaciais: letras tornam-se imagens, cores assumem função semântica, e a disposição gráfica instaura ritmos e tensões que solicitam uma percepção ativa do público.

O poema de Augusto de Campos não se organiza pela linearidade do verso, mas por campos de força visuais e sonoros que desafiam a leitura convencional. Resultantes de um processo iniciado pelo poeta ainda nos anos 1950, essas obras apresentam uma estrutura verbivocovisual, característica do Concretismo, na qual palavra, som, cor e forma se articulam de maneira indissociável. Ao mesmo tempo, incorporam recursos gráficos e digitais próprios do século XXI. Para além do amplo campo tecnológico oferecido pela computação gráfica, utilizada pelo artista desde o início dos anos 1990, Augusto de Campos também experimenta com elementos pontuais de seu contexto, com a ideogramática e a lógica matemática, além de procedimentos de intertextualidade que dialogam com referências como Marcel Duchamp, James Joyce e Fernando Pessoa, entre outros, bem como com estratégias associadas ao conceito de “ready-made”.

Nas obras Esquecer (2017) e Vertade (2021), a leitura deixa de ser linear e torna-se também perceptiva, quase física, exigindo do leitor um acompanhamento atento. Em Vertade, Augusto de Campos engana o olhar por meio da troca das letras D e T nas palavras antônimas verdade e mentira, instaurando um curto-circuito semântico que tensiona a confiança na leitura. Já em Esquecer, o artista promove a perda progressiva das palavras a partir de um poema preexistente, resgatado e inserido sobre a superfície de um céu nublado. À medida que atravessam as nuvens, os vocábulos se esmaecem e se confundem com a imagem, provocando um efeito de apagamento visual que se converte em reflexão sensível sobre memória, esquecimento e tempo. Este último, aliás, é também referência central do título da mostra, pós poemas, em que o termo “pós” carrega uma duplicidade semântica: indica tanto o depois quanto o plural de pó, matéria residual do que foi.

Serviço

Exposição | pós poemas

De 5 de fevereiro a 7 de março

Segunda, das 10 às 18h, terça a sexta, das 10 às 19h, sábado, das 11 às 17h

Período

Detalhes

A Olho Nu, maior retrospectiva realizada pelo prestigiado artista brasileiro Vik Muniz chega ao Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Bahia (MAC_Bahia). Com mais de 200 obras distribuídas em 37 séries, A

Detalhes

A Olho Nu, maior retrospectiva realizada pelo prestigiado artista brasileiro Vik Muniz chega ao Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Bahia (MAC_Bahia).

Com mais de 200 obras distribuídas em 37 séries, A Olho Nu reúne trabalhos fundamentais de diferentes fases da trajetória de Vik Muniz, reconhecido internacionalmente por sua capacidade de transformar materiais cotidianos em imagens de forte impacto visual e simbólico. Chocolate, açúcar, poeira, lixo, fragmentos de revista e arame são alguns dos elementos que integram seu vocabulário artístico e aproximam sua produção tanto da arte pop quanto da vida cotidiana. O público poderá acompanhar desde seus primeiros experimentos escultóricos até obras que marcam a consolidação da fotografia como eixo central de sua criação.

Entre os destaques, a exposição traz quatro peças inéditas ao MAC_Bahia, que não integraram a etapa de Recife: Queijo (Cheese), Patins (Skates), Ninho de Ouro (Golden Nest) e Suvenir nº 18. A mostra apresenta também obras nunca exibidas no Brasil, como Oklahoma, Menino 2 e Neurônios 2, vistas anteriormente apenas nos Estados Unidos.

A retrospectiva ocupa o MAC_Bahia e se expande para outros dois espaços da cidade: o ateliê do artista, no Santo Antônio Além do Carmo, que receberá encontros e visitas especiais, e a Galeria Lugar Comum, na Feira de São Joaquim, onde será exibida uma instalação inédita inspirada na obra Nail Fetish. Esta é a primeira vez que Vik Muniz apresenta um trabalho no local, reforçando o diálogo entre sua produção e territórios populares de Salvador.

Exposição A Olho Nu, de Vik Muniz, no Museu de Arte Contemporânea. Foto: Vik Muniz

Apontada como fundamental para compreender a transição do artista do objeto para a fotografia, a série Relicário (1989–2025) recebe o visitante logo na entrada do MAC_Bahia. Não exibida desde 2014, ela apresenta esculturas tridimensionais que ajudam a entender a virada conceitual de Muniz, quando o artista percebeu que podia construir cenas pensadas exclusivamente para serem fotografadas, movimento que redefiniu sua carreira internacional.

Para o curador Daniel Rangel, também diretor do MAC_Bahia, a chegada de A Olho Nu tem significado especial. “Essa é a primeira grande retrospectiva dedicada ao trabalho de Vik Muniz, com um recorte pensado para criar um diálogo entre suas obras e a cultura da região”, afirma.

A chegada da retrospectiva a Salvador também fortalece a parceria entre o IPAC e o Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil (CCBB), responsável pela realização da mostra e em processo avançado de implantação de sua unidade no Palácio da Aclamação, prédio histórico sob gestão do Instituto. Antes mesmo de abrir suas portas oficialmente na Bahia, o CCBB Salvador já vem promovendo ações culturais na capital, entre elas a apresentação da maior exposição dedicada ao artista.

Para receber A Olho nu, o IPAC e o MAC_Bahia mobilizam uma estrutura completa que inclui serviços de manutenção, segurança, limpeza, iluminação museológica e logística operacional, além da atuação da equipe de mediação e das ações educativas voltadas para escolas, universidades, grupos culturais e visitantes em geral. A expectativa é de que o museu receba cerca de 400 pessoas por dia durante o período da mostra, consolidando o MAC_Bahia como um dos principais equipamentos de circulação de arte contemporânea no Nordeste. Não por acaso, o Museu está indicado entre as melhores instituições de 2025 pela Revista Continente.

Com acesso gratuito e programação educativa contínua, A Olho Nu deve movimentar intensamente a agenda cultural de Salvador nos próximos meses. A exposição oferece ao público a oportunidade de mergulhar na obra de um dos artistas brasileiros mais celebrados da atualidade e de experimentar diferentes etapas de seu processo criativo, reafirmando o MAC_Bahia como referência na promoção de grandes mostras nacionais e internacionais.

Serviço

Exposição | A Olho Nu

De 13 de dezembro a 29 de março

Terça a domingo, das 10h às 20h

Período

Local

MAC Bahia

Rua da Graça, 284, Graça – Salvador, BA

Detalhes

A Nara Roesler São Paulo tem o prazer de apresentar Telúricos, exposição coletiva com curadoria de Ana Carolina Ralston que reúne 16 artistas para investigar a força profunda da matéria terrestre

Detalhes