Os limites entre sanidade e loucura, repressão e sublevação, são dois dos temais centrais de O Alienista, o famoso conto de Machado de Assis, publicado em 1882, antes sequer da Proclamação da República, foram transpostos para a 2019, na mostra de mesmo título de Rivane Neuenschwander, em cartaz até o próximo sábado, dia 18 de maio, na galeria Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel.

No texto clássico, o médico Simão Bacamarte funda em Itaguaí a Casa Verde, um retiro para loucos (é o termo usado pelo escritor), onde acaba internando, de forma intempestiva e autoritária, a maioria de sua população, para depois soltá-la, em parte por conta de revoltas populares. Ele então desconfia que os mais loucos seriam os mais sãos, e os recolhe. Mas o alienista acaba concluindo que o único louco de fato é ele, e se torna o único morador da Casa Verde, para morrer meses depois.

Não há dúvida que, nos últimos anos, o Brasil se tornou uma Itaguaí, dado o nível de insanidade no país, e a comparação que Neuenschwander empreende em sua mostra é notável por atualizar o momento atual pelo filtro machadiano: quem é louco? Afinal, a ascensão de figuras como Olavo de Carvalho e Damares Alves no governo brasileiro deixa dúvidas sobre a sanidade do próprio país.

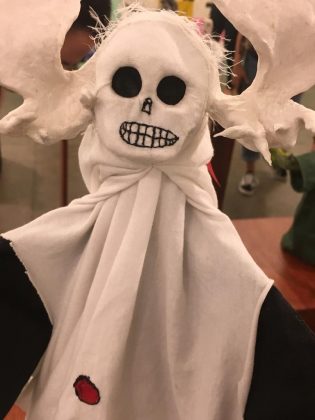

Assim, para tratar das figuras exageradas e caricatas em circulação, a artista usa esse mesmo tipo de recurso: os vinte bonecos que compõem o conjunto O Alienista são caricaturas tridimensionais. Como tais, são engraçadas e esquisitas, evitando aí um tom judicativo ou mesmo raivoso. É como olhar o presente sob uma ótica até ingênua, quase infantil, de bonecos feitos em papel machê, garrafas de vidro e outros materiais, em uma colaboração com seus filhos, Theo e Hannah, mantendo a parceria como estratégia permanente sua poética.

O conjunto não é totalmente literal. Há representações mais universais, como “O Militar”, encarnado como um dragão verde, e outras mais explícitas, como “O juiz de fora”, um rato de terno preto com a bandeira dos Estados Unidos em uma manga e limpadores de garrafa em outra, alusão clara a Sergio Moro.

Mas fazer rir em um momento de desgraça é uma benção e é por essa chave que a mostra escapa de se reduzir a uma crônica do momento atual. Ela acaba sendo tão estranha como o Brasil perversamente caricato de 2019.

Essas deformações reverberam nos outros dois grupos de trabalhos que completam a mostra no primeiro andar da galeria. O conjunto Trópicos Malditos, Gozosos e Devotos reúne quatro pinturas sobre madeiras que mesclam um estilo de xilogravura erótica japonesa, a shunga, com elementos da literatura de cordel. São trabalhos de um colorido pop _ outra das marcas da artista é essa referência a cores fortes_ para falar de um assunto delicado: o estupro como marca inaugural da miscigenação do Brasil. O espaço que reúne essa série é a antessala dos bonecos de O Alienista, o que serve como uma espécie arqueologia da loucura, afinal, que sociedade criada sob o signo da violência pode manter-se sã.

Já na sala com os bonecos, está o conjunto Assombrados, cinco pinturas sobre tecido, em estilo colcha de retalhos, onde ela mistura imagens e palavras dadas por crianças que participaram de oficinas preparatórias para a mostra O nome do medo, no Museu de Arte do Rio, em 2017. Novamente, Neuenschwander acrescenta outra camada à loucura, já que os medos aqui abordados são os menos infantis possíveis: bala perdida, fome, estupro, apontando novamente para uma sociedade absolutamente enferma.

Em O Alienista, Neuenschwander parece usar a leveza, a beleza e a diversão como uma porta de entrada para revelar a cultura enferma que se instalou no país: fascista, violenta e ignorante.