É em torno das ideias de diálogo e convivência que o atual presidente da Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, o banqueiro e colecionador José Olympio da Veiga Pereira, pensa o projeto curatorial da 34a edição do evento paulistano, a ser realizada em 2020. Se o momento político brasileiro é conturbado e de “fervura alta”, inclusive no campo cultural, não é hora de incentivar maiores polarizações e confrontos, diz ele. “A gente tem que ser capaz de dialogar, mesmo que não concorde com a ideia do outro”.

Com curadoria de Jacopo Crivelli Visconti, a Bienal tem como proposta “abraçar a cidade”, se espalhando no tempo – ao longo de todo o ano com exposições e performances – e no espaço – incluindo diferentes instituições da capital para além do Pavilhão do Ibirapuera. Essa escolha, afirma Olympio, segue também a linha de reforçar relações, criar conversas e incentivar diálogos.

Ao contrário de grande parte das pessoas que trabalham hoje na área cultural – que propõem um discurso de resistência e combate –, ele prefere adotar um discurso conciliador. “Tomar lado é a antítese do que estamos propondo. O que a gente está propondo é que os diferentes lados tem que ser capazes de se relacionar”, afirma Olympio, que é também conselheiro do MAM-Rio, do MASP, do MoMA (Nova York), da Tate Modern (Londres) e da Fondation Cartier (Paris).

Além disso, ele ressalta que considera tanto o ministro da Cidadania de Bolsonaro, Osmar Terra, quanto seu secretário de Cultura, Henrique Pires, “pessoas competentes, sensíveis e bem intencionadas em seus trabalhos”. Afirma, ainda, que se de um lado o presidente dá declarações polêmicas, de outro o congresso deu um exemplo de capacidade de diálogo ao aprovar a reforma da Previdência.

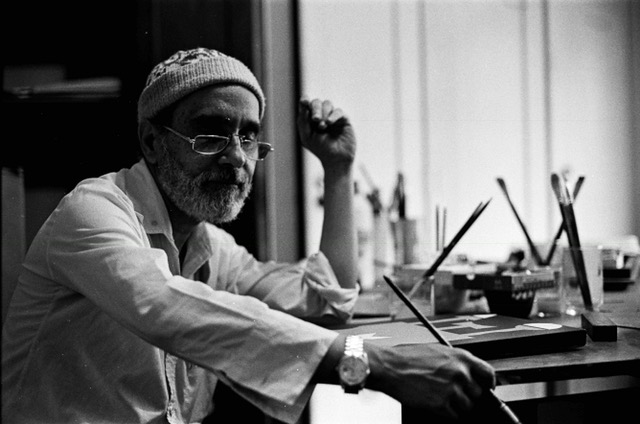

Em entrevista à ARTE!Brasileiros realizada na sede do Credit Suisse Brasil, banco do qual é o atual presidente, José Olympio falou sobre estes e outros assuntos relativos à Bienal e ao contexto político. Leia abaixo a íntegra.

ARTE!Brasileiros – Como você avalia estes primeiros meses à frente da presidência da Fundação Bienal?

José Olympio da Veiga Pereira – Eu estou há dez anos no conselho da Bienal, então não é que a Bienal seja uma novidade para mim. E há cerca de três anos eu já estava também presidindo um conselho consultivo internacional que nós formamos. Desde que assumi a presidência, acho que a coisa mais positiva foi me dar conta da qualidade dos profissionais que a gente têm. Conhecer mais a estrutura, os talentos e capacidades foi uma coisa muito boa. De fato temos um time muito competente, que veste a camisa, com muita experiência, o que é muito importante. Porque no nosso modelo de governança – temos um conselho de 60 membros, uma diretoria de dez membros, com mandato de dois anos renovável por mais dois – a função do presidente é limitada no tempo. O que garante a continuidade da instituição é o corpo de funcionários e de gestão que está lá, que mantém a memória e as capacitações, e acho que a gente está muito bem equipado nesse sentido.

No início do ano houve a escolha do Jacopo Crivelli Visconti como curador. Como foi esse processo e em que ponto anda o trabalho do time curatorial?

Sim, nesse período nós também avançamos com o projeto curatorial. Das propostas que eu recebi, que foram ótimas, se destacou a do Jacopo Crivelli, que convidou o Paulo Miyada como curador-adjunto e a Ruth Estévez, a Carla Zaccagnini e o Francesco Stocchi como curadores convidados. E nós criamos esse conceito de uma Bienal que abraça São Paulo, que se realiza não só no Pavilhão do Ibirapuera, mas numa rede de instituições culturais da cidade. Enfim, ao mesmo tempo estamos pensando sobre que outras missões a Fundação pode ter além da realização desta grande exposição a cada dois anos e das itinerâncias posteriores no Brasil e no exterior. E isso é uma coisa muito importante, essa promoção de arte global e brasileira entre um público brasileiro e global. Então acho que as coisas estão indo muito bem.

Existe a ideia de expandir a Bienal na cidade, com parcerias com outras instituições, mas também de expandir no tempo, com mostras que aconteçam ao longo do ano. Pode contar um pouco mais sobre isso?

Sim, são dois vetores. Então a Bienal vai começar em março, com três exposições individuais no primeiro semestre, de artistas que também estarão na mostra coletiva posteriormente. E nós teremos também no primeiro semestre três grandes performances apresentadas em momentos pontuais. E teremos também outros eventos ao longo do ano, educativos, debates, palestras etc.

E qual a ideia por trás dessas mudanças, dessa expansão? É parte de um desejo de expansão de público? Vem de uma percepção de que a Bienal ficava muito restrita a um período curto?

Eu acho que você tem toda a proposta curatorial que tem a ver com a poética das relações, a questão do ser humano ser capaz de se relacionar com alguém diferente dele. E eu acho que a formação dessa rede de instituições reforça a proposta curatorial, de criar diálogos. E a Bienal sempre foi um catalizador de atração de um público global e brasileiro que vem ver a exposição, o que faz com que todas as outras instituições culturais queiram caprichar na sua programação, fazer coisas especiais durante o período. Então por que não fazer isso em diálogo? Então vamos realmente oferecer ao grande público uma coisa muito interessante. Por exemplo, você pode ver na exposição coletiva da Bienal um artista que te interesse especialmente, e aí você tem a oportunidade de conhecer a produção dele mais profundamente em uma individual em outro museu. E aí perceber como é este artista visto individualmente ou como ele é visto em relação a outros artistas. E acho importante, para cumprir a nossa missão de promoção de arte, fazer uma coisa que tem impacto, oferecer um produto ao público que tenha interesse, que seja algo diferente. Nossa meta é transformar São Paulo em uma capital das artes plásticas, visuais, de setembro a dezembro do ano que vem. Fazer com que todo mundo que se interessa por arte sinta vontade de vir à São Paulo nesse período.

Uma das coisas que você propôs desde que assumiu tem a ver com um trabalho de criação de ferramentas voltadas à preservação da memória das artes, ampliando o papel, por exemplo do arquivo histórico da fundação, o Wanda Svevo. Poderia contar um pouco sobre isso?

Sim, isso está em formulação, mas é um projeto de mais longo prazo. A ideia é dar à Bienal uma missão institucional de ser um grande centro de memória de arte. Focado como um centro de estudos, de memória. O arquivo histórico Wanda Svevo já serve a um número grande de pesquisadores, mas acho que isso pode ser muito expandido. E estamos pensando como fazer isso.

Falou-se também num fortalecimento das relações da Bienal com a vida cultural no exterior, até pelo seu bom relacionamento com tantas instituições internacionais. Concretamente, o que isso significa?

A Bienal é a mais internacional das nossas instituições culturais. Ela promove este intercâmbio entre a arte global e a brasileira desde o início – inclusive, antigamente havia até representações internacionais. E eu acho que a gente tinha perdido um pouco esse contato. Então desde 2016 a gente começa, através da criação deste conselho consultivo internacional, a se reconectar ao mundo global das artes. Hoje já temos 11 membros neste conselho, gente da França, da Inglaterra, da Holanda, dos EUA, Argentina, Alemanha etc. Porque a gente quer a ajuda dessa rede para promover a Bienal, para conseguir acessar artistas que eventualmente a gente queira trazer, buscar obras importantes. Porque nós somos essa instituição global. E a nossa Bienal, embora muito tradicional e antiga, perdeu parte de sua relevância com o tempo por conta inclusive da infinidade de bienais que foram criadas ao redor do mundo. E o que a gente quer é afirmar a nossa importância, disputar o nosso espaço de luz ao sol neste mundo superpovoado de bienais.

Quando foram apresentadas as primeiras linhas do projeto curatorial, tanto o senhor quanto o curador falaram da importância de não alimentar polarizações neste momento político conturbado, de incentivar a capacidade de dialogar e conviver. Passados cerca de três meses, com os acontecimentos políticos recentes, com as políticas e declarações polêmicas do presidente, como você enxerga essa questão?

Acho que só reforçou o que a gente quer enfatizar. E acho que essa não é uma questão brasileira, mas é global. Quando você olha o que está acontecendo nos EUA, na Europa – com o Brexit, ou na França, na Itália –, a gente está infelizmente em um momento de polarização, de intransigência com a ideia do outro. E o que a gente quer buscar é dizer que, apesar disso tudo, a gente tem esperança. A gente tem que ser capaz de dialogar, mesmo que não concorde com a ideia do outro. É curioso, porque a gente vê ao mesmo tempo, aqui no Brasil, dois exemplos: de um lado as declarações do presidente, mas de outro um congresso que se uniu e aprovou a reforma da Previdência, com 379 votos, unindo partidos das mais diferentes colorações. Então há uma esperança.

A aprovação da Previdência é para você um exemplo da capacidade de união?

É uma capacidade de diálogo. Não é porque a ideia é do outro que ela é ruim. Temos que pensar no país, temos que ter esse diálogo.

Agora, pensando a Bienal como este evento que trabalha com arte, experimentação e criação – um espaço muitas vezes de radicalidade –, é possível neste contexto se furtar de tomar posição, tomar lado?

Tomar lado é a antítese do que estamos propondo. O que a gente está propondo é que os diferentes lados tem que ser capazes de se relacionar. E no fundo, o que a gente quer mostrar é que o lado que a gente está tomando é o lado de que o diálogo tem que acontecer. De que a polaridade não leva a lugar nenhum. Essa é a nossa posição com a proposta curatorial.

Enquanto presidente da Bienal, você lida diretamente com as áreas de cultura e educação. De modo geral, são duas áreas que parecem bastante ameaçadas pelo atual governo, seja na mudança na Rouanet, na Ancine, nas propostas de corte ao sistema S, nos cortes de verbas nas universidades…. Você não enxerga um discurso violento contra essas áreas? Não vê riscos com as novas políticas?

Olha, eu acho que ninguém discute que a educação é fundamental para o desenvolvimento do nosso país. Isso para mim está claríssimo. Você pode debater a efetividade ou não dos nossos esforços na educação, mas a importância da educação é inquestionável. Não vejo ninguém questionar isso. E acho que na cultura a gente tem um defensor, que é o ministro da Cidadania Osmar Terra. Vejo pela própria maneira como ele lidou com a Lei Rouanet. Havia muito medo do que poderia ser feito e acho que a solução final proposta por ele foi uma solução ok. E acho que tanto ele quanto o secretário de Cultura Henrique Pires entendem a importância da cultura e a importância de instituições culturais como a nossa, que foram absolutamente preservadas com a mudança na Lei de Incentivo à Cultura. Então eu acho que tem muito barulho, mas ameaças concretas eu não vejo, ao menos olhando do ponto de vista de entidades culturais como a Bienal e museus. Não quero entrar na seara de produtores culturais ou cinema etc., que aí é outro campo. No campo onde eu milito e participo eu acho que a solução que foi dada está ok.

E quanto aos artistas, você não percebe um clima de apreensão? As pessoas não estão assustadas?

Existe sim. Veja bem, está todo mundo assustado. Existe medo. Eu só espero que com o tempo essa poeira, essa temperatura, abaixe. Mas, sem dúvidas, a gente está vivendo um momento de fervura alta.

Vou insistir um pouco nessas questões políticas, que me parecem muito relevantes neste momento. Em entrevista recente você disse que achava que a cultura poderia ser valorizada independentemente de estar debaixo de um ministério ou de uma secretaria, que o fim do Minc não era um problema em si. Olhando agora, você acha que a cultura está sendo valorizada?

Acho que tem muito ruído em torno da cultura. Não tanto nas artes plásticas, não nas instituições culturais, mas em outras áreas, como na discussão em torno da Ancine. Enfim, espero que isso seja melhor endereçado. Mas continuo com a minha visão de que a gente não necessariamente precisa de um ministério para valorizar a cultura. Você pode ter um ministério e mesmo assim a cultura ser desvalorizada, porque o ministério não tem orçamento, não tem foco – como já aconteceu –, aí não adianta. Eu só acho importante deixar o registro de que eu considero tanto o ministro Osmar Terra quanto o secretário Henrique Pires pessoas competentes, sensíveis e bem intencionadas em seus trabalhos.

Por fim, eu queria saber sua avaliação sobre a participação brasileira na 58a Bienal de Veneza, com o trabalho de Bárbara Wagner e Benjamin de Burca, e na perspectiva em relação à participação brasileira na 17a Bienal de Arquitetura, em 2020, ambas ligadas à Fundação Bienal.

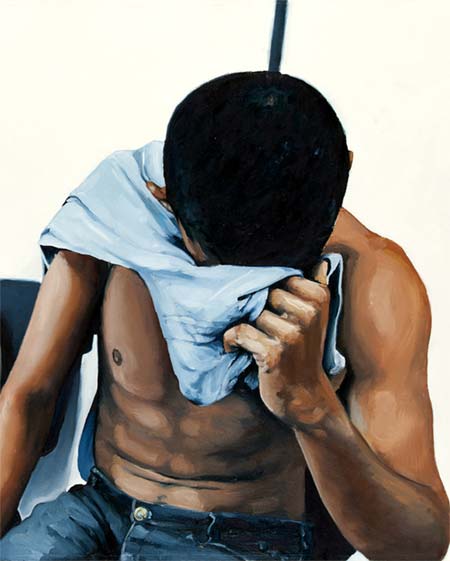

Acho que já na gestão anterior nós fizemos um gol com a participação da Cinthia Marcelle. Foi a primeira vez que o Brasil ganhou uma menção honrosa com o seu pavilhão, o que é uma coisa extraordinária. A escolha agora da dupla Bárbara Wagner e Benjamin de Burca, com a obra Swinguerra, também foi extremamente feliz. Eu fui à abertura e pude constatar o sucesso do pavilhão mesmo antes de toda a imprensa europeia dar o pavilhão brasileiro como um dos dez melhores. Foi um baita sucesso, impecavelmente realizado, deu orgulho da nossa sala e das soluções técnicas encontradas. Acho também que a diretriz de ter um artista só é a mais adequada, tem mais força. E agora vamos apresentar o Swinguerra na Bienal, para o público brasileiro, essa obra que é absolutamente sedutora e hipnotizante.

E sobre a Bienal de Arquitetura…

Temos planos igualmente ambiciosos para a nossa representação na Bienal de Arquitetura de Veneza. Já está endereçado, mas vamos revelar em breve.