For Lisette Lagnado, one of the four curators at the 11th Berlin Biennial, the new coronavirus highlighted even more issues that the event itself, whose official opening took place on September 5, three months late, had set out to discuss in 2020 “We were talking about necropolitics, fanaticism, capitalist patriarchy, extraction and ecological devastation. The pandemic only came to deepen the gap that separates the countries of the global south from the place where we are,” pondered Lisette in her opening speech at the VI International Virtual Seminar ARTE! Brasileiros.

The conversation was mediated by the journalist Fabio Cypriano, with the participation of the Spanish Agustín Pérez Rubio (from the curatorial team of the Berlin Biennial, alongside Lisette, the Chilean María Berríos and the Argentine Renata Cervetto) and two of the artists selected for the exhibition , the Brazilian Aline Baiana and the Guatemalan Edgar Calel.

Still at the opening, Lisette expressed some discomfort with the seminar’s subtitle, The Art of Possible. “Our job as producers and cultural agents is always to deal with the impossible,” she said. “It is very difficult to put the concept of solidarity when an international, European biennial announces its dates, despite the fact that the artists are still in lockdown in the countries of the global south. I wanted to draw attention to the violence intrinsic to the initial decision to make the biennial happen in 2020 “.

For the curator, the “most substantial chapter of the biennial” – whose epilogue, entitled The crack begins within, will be shown until November 1 in the German capital – had been opened in September 2019, with workshops, small exhibitions and performances, in the Berlin Wedding neighborhood, in a space that proposed listening and exchanging with local residents, mostly immigrants.

“There was a whole dynamic of being together and suddenly we were interrupted in this way of working”. It was necessary, continued the curator, to create what she calls an ethical protocol: “To say that we would not give an inch in our position and, in this sense, the word possible is dangerous because it may seem opportunistic. Rosa Luxemburg said that opportunism is the art of the possible. And I want to insist that, when doing a biennial in these conditions, we have to worry about our own principles. And don’t bend to those dictated by an exceptional situation.”

Activist artist

In the virtual seminar, Lisette exemplified the political weight of the show, initially presenting the American Marwa Arsanios and her trilogy Who’s afraid of ideology?. The work reflects, said the curator, an ecological feminism that since 2017 marks the work of Marwa, together with women who participate in movements for the fight for land, in places like northern Syria and Colombia.

“[It is something that] recontextualizes a feminism of the 1990s, which concealed the ideological analysis by stating that gender equality was already a step over,” she said. “With this criticism, Marwa went looking for a feminism beyond a kind of liberal middle class life, which she found in ecological activism. In this film, the rural area is the territory where the fight for land takes place and where these women are also guardians of seeds, water sources and biodiversity. We see here an example of the figure of a caring and activist artist.”

Marwa’s activism ends up finding echoes in the sphere of contemporary art, also regulated by the logic of extraction, said the curator. “I bring, like her, the concern to avoid transforming these precarious lives into commodities worshiped at international biennials. How to prevent the appropriation of these genuine knowledges from turning into something else through the exploitation of others’ sores”.

The cross of colonialism

Aline Baiana began her participation by questioning the difficulty, on the part of science, of perceiving Afro-Brazilian or indigenous knowledge as such, relegating to these perspectives a fabulous character, often in children’s books.

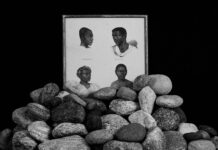

“What I try to do with my work is to share these understandings of the world and to tension them with the Western understanding, hegemonic […] a way to collaborate for the anti-colonial struggle”, explains Aline, who presents in Berlin the installation The southern cross.

“This work started, as an idea, when the environmental crime took place in Mariana [the Brumadinho dam burst in January 2019]. I was shocked and disturbed seeing those images of the river dead by a company that has already taken its name [Vale do Rio Doce], which made me think of this place of infinite exploration that Brazil and other southern countries occupy. And as the mining risks are obliterated from the final product, they are left to the populations. ”

The choice of the work’ name also contained a criticism: the constellation, symbol of Mercosur and present in flags of many countries in the hemisphere, represented as a cross, from a Christian perspective, in a colonizing act.

Aline also explained why the idea of “art of the possible” bothered her, remembering two phrases: “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”, by the British Mark Fisher, in the book Capitalist Realism. “We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable – but until then, the divine right of kings also seemed. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art”, by American Ursula K. Le Guin. “What I think as an artist is that the role of art is perhaps to provoke reconnections, to imagine other possibilities”, concluded Aline.

Ancestrality and resistance

In his speech, Edgar Calel initially considered that we are the product of nature and the ancient cultures of the world, such as the one he was born and raised in Guatemala. The artist then read an excerpt from an account of the creation of the universe according to Popol Vuh, a Mayan documentary record from the 16th century.

“Under this panorama of ancestral indigenous literature, it seems interesting to me how, through art, people are able to cross different physical and time spaces, and with that we unite ancient and contemporary situations, with the need to listen to the past for project the future. Part of my job is to do these physical and temporal journeys as well”, said Edgar.

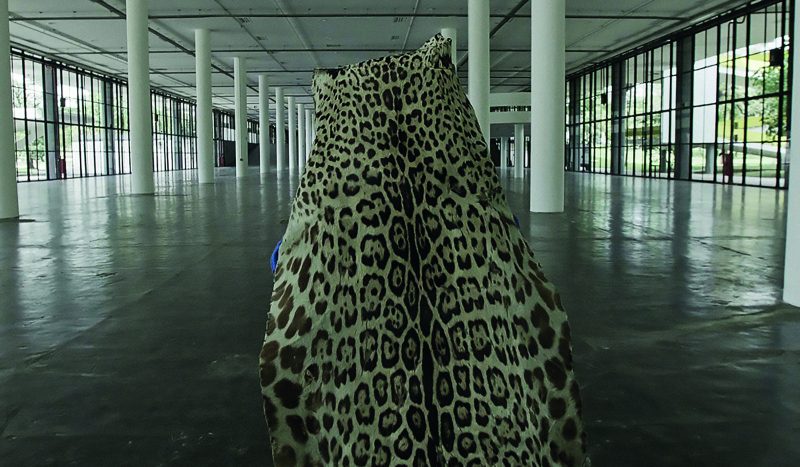

Acima, a performance decolonizadora de Edgar Calel, que veste pele de onça em ritual ancestral no prédio da Bienal (SP).

The artist took the video Sueño de obsidiana to the Berlin exhibition, made in collaboration with São Paulo native Fernando Pereira Santos. In it, Edgar represents an indigenous ritual linked to the land, having as scenario one of the icons of Brazilian modernist architecture, the Bienal building, in São Paulo. With the skin of a jaguar, his animal spirit according to the Guatemalan tradition, or a blue sweater, which is displayed in the daadgalerie, and in which he sewed the names of the indigenous languages of his country, the artist speaks of anti-colonial resistance through reconnection with ancestry.

“Taking this walk in that concrete building, being an indigenous person of Mayan descent, is a statement about the destruction of the limits, the borders imposed between countries like Brazil, Paraguay, Bolivia, etc. We are all one. This, for me, is something fundamental, that we must contribute to this other possible world”, he argued.

God and Devil

“This is a biennial of sensitive capital, of relationship capital,” said Agustín Pérez Rubio, when he began his participation. “And also, what perhaps the pandemic has made us value it more, an idea of cure, of a healer, not only of healing anything, but of accompanying, caring,” he said.

Agustín used the image of Edgar dressed in jaguar skin, in the Bienal building, to talk about another section of the Berlin exhibition: fanaticism and the god of capitalism, of the internet and, in the case of the Guatemalan artist’s work, an idea of contemporary art church, incorporated by the modernist construction. According to him, it is important to open cracks in institutions such as the biennial and museums, for these questions: “For artists like Edgar to show us how, in an icon of Brazilian modernity, the denial of knowledge, which has been segregated for years, is implicit”, argues Agustín.

The curator then mentioned the work of Antonio Pichillá, also from Guatemala, presented at the Berlin exhibition: the video Action of a tree character, shown at the Gropius Bau, which houses the segment The inverted museum of the biennial, an attempt to “counter-narrative” to the Eurocentric perspective on art. “To understand how this colonial vision is perpetuated by the institutions,” said Agustín, citing the Humboldt Forum, a museum space that will open later this year in Berlin.

Agustín also criticized the reception of the works by German journalists: “They can only see the ethnography of these works and fail to consider them from a philosophical, aesthetic and artistic root as contemporary works. Or, for them, they are works with something esoteric. It is very interesting to see that all these critics and German culture have allowed this racism and this way of seeing otherness to be perpetuated, based on their Eurocentric ethnography”, he said. “And since esotericism in Germany is very close to the extreme right, they prefer not to talk about these works”.

Demolition, retribution

How, then, to avoid the extraction of biennials and other cultural events? How did the curatorial quartet at the Berlin exhibition deal with the issue? “Patriarchy, colonial sores, are suffocating us, and we have to react even with violence. On the other hand, there is a question of care. So, how to be violent and, at the same time, welcome other voices, and these more vulnerable lives? What always guides me is a mixture of intuition and ethics. And in that sense, listening has been our compass”. For Agustín, in addition to listening, a non-extractive way would be to understand that you take something, but also return it. “The idea of restitution, with artists, communities, vulnerable museums”, he concluded.

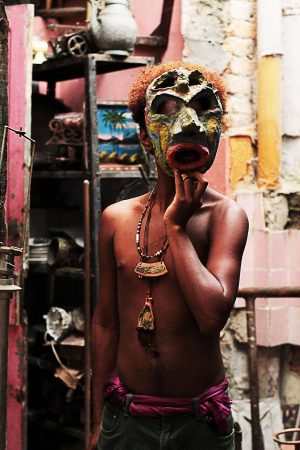

Strategies of the possibleIn a video conference of the Goethe-Institut, the Argentine Osías Yanov and the Brazilian Castiel Vitorino talked about the works they exhibited in Berlin To complement the open seminar, the Goethe-Institut Rio also held a specially organized videoconference for a group of guests who were unable to travel when the 11th Berlin Biennial opened in September. Among them, curators, artists, and managers from different museums and from different units of the Goethe-Institut in Latin America. On this day, in addition to the curators, the artists Osías Yanov (Argentina) and Castiel Vitorino (Brazil) participated. In Berlin, Osías participated in the space dedicated to the show’s experiments, the ExRotaprint. Part of his project was compromised by the sanitary restrictions of the pandemic, including his group exercises, which he had already done in Argentina, in a reflection on the repression of bodies, among other issues.  The artist sought to maintain the necessary distance contact with his group of performers, who drew drawings and read short stories. The results were presented at the biennial, along with elements dear to his artistic research: spoons – cucharitas – that refer to the act of sleeping embraced with someone, and appeared in sculptural forms, and salt – a substance linked to the notion of purification and healing. Through loudspeakers, the sound recording of the readings made acrylic tables vibrate on the floor, creating drawings in the salt in contact with them. Lisette Lagnado stressed the importance of listening in Osías’ work and mentioned another experiment carried out on ExRotaprint with the feminist collective FCNN, which discussed the institutional space that art leaves for young mother artists, who have nowhere to leave their children. The presence of women at the biennial, in the fight against patriarchy, is also one of the important themes of the exhibition. In Berlin, the curator had the opportunity to read a book on motherhood, by the Egyptian Iman Mersal, which brought up the idea of a child destroying the possible future of the mother, in a hurry to reach the new world. “It was something we were feeling about the biennial, facing the pandemic, and we borrowed this notion of crack, fissure, for the title.”  Castiel took a series of photographs to Berlin in which he appears wearing masks bought at an antiques store in Santos (SP), sold as African, but actually made by a friend of the store owner. With the work, the artist exposes the exoticization of the colonizing discourse about the cultures of the continent. “With photography, I try to create images to remind me of the possibility of living outside circumscribed and ordered by racial mythology,” he said. |

Detalhes

O Sesc Vila Mariana recebe a exposição inédita Jardim do MAM no Sesc, uma correalização do Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo e do Sesc São

Detalhes

O Sesc Vila Mariana recebe a exposição inédita Jardim do MAM no Sesc, uma correalização do Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo e do Sesc São Paulo. A mostra tem curadoria de Cauê Alves e Gabriela Gotoda e reencena na entrada do Sesc Vila Mariana elementos do Jardim de Esculturas do MAM. Nela, o público poderá apreciar obras da coleção do MAM, entre esculturas icônicas de Alfredo Ceschiatti, Amilcar de Castro e Emanoel Araújo, e trabalhos que exploram críticas sociais, como as obras de Regina Silveira, Luiz 83 e Marepe.

Para a presidente do MAM, Elizabeth Machado, a parceria com o Sesc reforça o compromisso do museu em ampliar o acesso à arte: “O acervo do MAM é um patrimônio vivo, e essa exposição no Sesc Vila Mariana permite que um público ainda mais amplo entre em contato com obras fundamentais da nossa história, promovendo o encontro e a reflexão sobre a arte brasileira. O Sesc é um parceiro longevo do MAM, e essa colaboração reafirma nossa missão conjunta de ampliar o acesso à cultura.”

Os artistas participantes da mostra são Alfredo Ceschiatti, Amílcar de Castro, Bruno Giorgi, Eliane Prolik, Emanoel Araujo, Felicia Leirner, Haroldo Barroso, Hisao Ohara, Ivens Machado, Luiz83, Marepe, Mari Yoshimoto, Márcia Pastore, Mário Agostinelli, Nicolas Vlavianos, Regina Silveira, Roberto Moriconi, Rubens Mano e Ottone Zorlino.

A seleção de obras inclui peças que já integraram o Jardim do MAM, além de trabalhos do acervo do museu que dialogam com temas como natureza, cidade e materialidade. A montagem no Sesc Vila Mariana recria a dinâmica do Jardim de Esculturas, utilizando elementos cenográficos que evocam a topografia sinuosa do Parque Ibirapuera projetada pelo escritório do emblemático arquiteto paisagista Burle Marx, estimulando novas interações entre corpo, espaço e arte.

Inaugurado em 1993, o Jardim de Esculturas do MAM marca uma iniciativa que reavivou a coleção do museu em um espaço próprio, gratuito e de grande circulação de pessoas. “Ao propor uma espécie de reencenação do Jardim do MAM na Praça Externa do Sesc Vila Mariana buscamos elaborar a ideia de que, assim como o espaço do jardim no Parque Ibirapuera, o espaço do Sesc funciona como um centro de encontros urbanos”, diz Cauê Alves. “A exposição inclui obras da coleção do MAM que se relacionam, por diferentes vias, com a natureza, o corpo, a cidade, a materialidade, e com linguagens que expressam algumas das tensões inescapáveis à sociedade.”, completa o curador.

A proposta da exposição do Jardim do MAM no Sesc Vila Mariana é estimular essa relação entre corpos, obras e espaço, transformando a Praça Externa da unidade em um território de circulação, experimentação e descoberta. Sem a pretensão de emular o paisagismo do parque, a cenografia do projeto recria as curvas e volumes que marcam o jardim original, propondo um ritmo espacial entre as esculturas. Para Gabriela Gotoda, curadora da exposição ao lado de Cauê Alves: “Se o princípio mais original e autêntico da arte moderna é de que ela se aproxima da vida, um museu que se dedica a colecioná-la e atualizá-la no seu tempo presente deve continuamente se esforçar para oferecer aos públicos possibilidades de fruição que não os distanciam das suas realidades, e sim vão de encontro a elas.”

MAM Educativo

Durante o período da exposição, o público poderá participar gratuitamente de atividades educativas promovidas pelo MAM Educativo, que desenvolve programas e projetos em diálogo com seus públicos, por meio de uma programação acessível e gratuita que busca equiparar oportunidades e reduzir barreiras físicas, sensoriais, intelectuais, sociais ou de saúde mental.

Inspiradas nas experiências realizadas no Jardim de Esculturas do museu no Parque Ibirapuera, parte das ações de maio do MAM Educativo serão adaptadas ao espaço do Sesc Vila Mariana, propondo diferentes formas de interação entre corpos, obras e o ambiente expositivo. Voltadas a públicos de todas as idades e perfis, as atividades buscarão estimular novas formas de olhar, habitar e refletir sobre o espaço urbano por meio da arte.

As atividades serão divididas em programas. “Contatos com a arte” promove a formação cultural de professores, educadores, pesquisadores e estudantes universitários, fomentando seu papel de multiplicadores das diferentes expressões artísticas e abordagens pedagógicas a partir de processos criativos diversos. Já “Família MAM” promove o encontro do universo artístico do museu com as culturas da infância, através de narrações de histórias, brincadeiras, oficinas artísticas, visitas mediadas seguidas de experiências poéticas, entre outras atividades. Em “Domingo MAM” estão atividades que convidam o público a experimentar diversas linguagens artísticas a partir de eixos temáticos que englobam dança, música, cultura popular, cultura de rua, debates e oficinas plásticas.

Tem ainda o “Programa de Visitação”, que atende a todos os perfis de público e incentiva o acesso à arte e à cultura por meio do exercício do pensamento crítico. Fazem parte do programa visitas mediadas, experiências poéticas e o programa de relacionamento com escolas parceiras. Visitas mediadas com o MAM Educativo são conversas nas quais é estimulada a reflexão crítica por meio da arte e experiências poéticas, que aproximam o público do museu de vivências e processos artísticos. Agendamentos de grupos para visitas na exposição Jardim do MAM no Sesc são realizados pelo e-mail educativo@mam.org.br.

A programação traz ainda atividades que fazem parte da Semana Nacional de Museus – iniciativa do Instituto Brasileiro de Museus (Ibram) em comemoração ao Dia Internacional dos Museus (18 de maio) e que, em 2025, acontece de 12 a 18 de maio sob o tema “O Futuro dos Museus em Comunidades em Rápida Transformação” – e da Semana Mundial do Brincar – ação promovida pela Aliança pela Infância que convida a sociedade a valorizar o brincar e a importância da infância e que, em 2025, terá como tema “Proteger o Encantamento das Infâncias” e ocorrerá de 24 de maio a 1 de junho.

Serviço

Exposição | Jardim do MAM no Sesc

De 14 de maio a 31 de agosto

Terça a sexta, das 7h às 21h30, aos sábados, das 10h às 20h30, e aos domingos e feriados, das 10h às 18h

Período

14 de maio de 2025 07:00 - 31 de agosto de 2025 21:30(GMT-03:00)

Local

Sesc Vila Mariana

Rua Pelotas, 141 - Vila Mariana – São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

Um celeiro em chamas. Um sonho-memória. Uma atmosfera enevoada. O silêncio e o tempo suspensos. A cena é captada em um plano lento e alongado em que a câmera

Detalhes

Um celeiro em chamas. Um sonho-memória. Uma atmosfera enevoada. O silêncio e o tempo suspensos. A cena é captada em um plano lento e alongado em que a câmera vai se aproximando. Um plano sequência da personagem que atravessa silenciosamente o campo e se depara com o celeiro completamente tomado por labaredas, sendo consumido pelo fogo. O som das fissuras da madeira se dissolvendo em chamas e a fumaça cinzenta envolvendo o local e ela, esperando, imóvel diante do colapso inevitável, reverenciando o que é maior que sua pequeneza. A cena, retirada de “O Espelho” de Andrei Tarkovsky, reflete sua trajetória fílmica da meditação visual. Diante do tempo, da transformação e da fragilidade da vida, as chamas se condensam e o que permanece é a percepção da contemplação, do abalroamento da dimensão interna mental com o externo.

Turvo Reflexo é o entre, que oscila entre o visível e o oculto, em camadas translúcidas que se completam a cada olhar atento, a relação reflexiva sobre a velatura e a capacidade turva. Diante do conjunto matérico de João Trevisan somos convocados a esperar o esticamento do tempo, bem como a personagem não corremos para apagar o fogo, sentimos uma calma irrompente que evoca uma presença contemplativa, do corpo diante da matéria, Trevisan esculpe o tempo e hipnotiza como Tarkovsky.

Trevisan opera no alongamento da percepção, agindo em parceria com a matéria, forja e embosca sua técnica e azeita a própria linguagem. Há uma reflexão compositiva de seu trabalho, a imagem que se dissipa e envolve o olhar, que percorre a claridade, a luz se apresenta como uma partitura, em que cada pintura emite uma vibração. A exposição nos permite acessar cinco séries de sua produção, algumas ainda inéditas – Concomitante, Paisagens, Unidade luminosa, Monocromo e Intervalos. São atos compositivos de um grande motivo, como em uma ópera, ao se referirem ao mesmo universo, em diálogo dos pares e coesos com a peça completa. As séries são interligadas intimamente, em 2018 pintou o primeiro Monocromo, mesmo ano que pintou o primeiro Intervalo, isso demonstra o desdobramento de seu processo. Deriva de um modo não linear e ramificado, em que não há centro e hierarquia, mas que paradoxalmente, tudo é central, os blocos densos de cor são unidos pela fatura, se prolongando uns dos outros.

Diante de uma contemporaneidade em que tudo é descartável, instantâneo e comprimido, o tempo se torna alongado e embarcar na luminosidade da pintura é ampliar o sensível. João Trevisan nos convida a habitar o espaço do silêncio e da contemplação ao consolidar a pintura no tempo dilatado.

Os títulos nos trazem informações óbvias com toques curiosos, ora mais diretos, ora mais lúdicos. Nos versos das obras há algumas deliciosas surpresas, rastros deixados pelo artista, que nos aproximam de sua presença, como em Intervalos, nas manhãs, eu sinto falta de você.

As gradações de cor variam na espessura, demonstrando maior ou menor opacidade, em que camadas mais profundas transparecem e se interferem. Notamos a destreza técnica do artista, em que as cores, mesmo quando empregadas sempre da mesma maneira, são sempre diferentes, se os pretos irão se complementar ou interferir nas cores de cobertura, se aparecem ou se dissolvem, e indicam uma coparticipação entre a tinta a óleo e o veludo criado pela encáustica.

Insere de modo singular pequenos desafios ao olhar, certas irregulares propositais, como em Concomitantes. Deslocamentos sutis, como uma pequena margem no início de um parágrafo, demonstram uma racionalidade em pensar o trabalho de maneira calculada, mas não apenas, há algo de intuitivo na relação das cores, o processo de feitura é metódico, desde a profundidade do chassi até a finalização. Esse jogo da percepção só é criado no contato com o presenciador, que ao botar reparo em deslizes das formas, evidencia a força propositiva do artista em suas ondas cromáticas ritmadas.

A tela é encorpada, inicia com camadas de gesso cruzadas, diluídas até o ponto de engrossarem, adicionando corpo ao processo, para então seguir com a adição de dez a doze camadas de preto. Transborda a fatura e articula o corpo da pintura a partir do hábito da repetição. Quando secas, realiza a velatura da superfície, uma cobertura diáfana com o preto, em que as cores sutilmente se invisibilizam, e com a limpeza posterior, o corpo pictórico se eleva ao equilíbrio. Retira o excesso, deposita luz, deposita pigmento, esculpe o corpo da pintura ao modelar sua relação com a luz. Elabora um processo de enceramento da pintura, em que as ranhuras vão sendo preenchidas pelos pretos, sendo possível a percepção da luminosidade residual proveniente da base branca, revelando o processo de retração do pigmento com a secagem, quando suas partículas se adensam e se aproximam, revelando parcialmente o fundo.

Há uma vontade derivada da escultura, de um ciclo poético que surge do papel, retorna para as esculturas e eclodem nas pinturas. As linhas se manejam no tridimensional como no bidimensional, sua fatura pictórica ergue-se como forma no campo escultórico. Modela fibras de tinta, ocasionando uma ilusão luminosa pelo volume, há um certo aspecto enigmático de tentar decifrar de onde vem a cor e para onde vai a centelha cromática. Engendra um método repetitivo que beira a meditação budista, repete o processo, repete a forma, repete o preparo e as camadas. A relação com a pintura é corpórea, na qual o gesto do artista se prolonga e o que vemos é o turvo reflexo do derramamento de Trevisan.

O artista é atravessado pela vida fora do ateliê, conduz sua feitura por contaminações urbanas, a capital do país, Brasília, não é apenas sua morada, mas é igualmente o habitar da pintura. Quando seca, a paisagem da cidade revela um vermelho terroso, o cerrado em sua constituição genuína, berço do Pequi e do Baru. Por vezes visualiza um ar menos árido, um momento mais orgânico e nutritivo – Trevisan é permeado por essas manifestações, se deixa ser infiltrado.

A percepção está no campo sensorial, sua prática se completa na ativação do olhar do observador, que deixa de ser externo e se torna parte constituinte da projeção das cores, o encontro quintessencial entre o corpo matérico e o corpo sensível. Somos convocados a nos aproximar e afastar dos trabalhos, de modo que Trevisan propicia uma experiência visual da imersão em seu universo, uma forma emocional de estar diante do seu contorno. A feitura pictórica é uma conversa atenta entre a matéria e o fazer poético, a aplicação da cor é tão relevante quanto a escolha desta. A coincidência da opacidade com o brilho e o encontro da encáustica com o volume do óleo, revelam como a pintura conserva vestígios do instrumento e da performance gestual com o material, o artista indubitavelmente está ligado às veleidades e aspirações da matéria.

Um pulso rítmico nas formas que se repetem na construção matérica, nos deslocamentos e nos espaços, na potência da presença das cores sobre as outras. A poética de Trevisan é uma chama que se espalha pelo celeiro, não como destruição mas como um processo de disseminação. Se torna carvão, fuligem e a fumaça que alastra o ambiente, se dissipa em neblina de maneira sutil. O rastro nevoeiro é uma potência, o que se vê e sente vai gradualmente sendo velado e se transmuta, recobre a paisagem, interrompe a percepção e convoca a pausa. A rendição do tempo e a espera do revelar o que é fugidio ao olhar é como experienciamos Turvo reflexo.

A veladura na trama da superfície é a névoa ramificada pelo espaço expositivo, uma vinculação rítmica que emana de todos os trabalhos, o locus da pintura é sempre revisitado, se articula em outras tantas possibilidades, que ciclicamente retornam e se complementam. Ao embarcar em sua prática poética, notamos nuances, sutilezas da fatura da pintura que vão se consolidando no olhar de quem se depara com suas paisagens geometrizantes e, em Turvo Reflexo, nos absorvemos em uma ocupação luminosa e contemplativa de João Trevisan.

Serviço

Exposição | Turvo Reflexo

De 15 de maio a 19 de julho

Segunda a sexta, 10h às 19h, sábado, 10h às 15h

Período

15 de maio de 2025 10:00 - 19 de julho de 2025 19:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

Simoes de Assis Curitiba

Alameda Dr. Carlos de Carvalho, 2173a - Batel Curitiba - PR

Detalhes

O grid só existe quando criado, é uma estrutura organizacional, composta por linhas horizontais e verticais que desenham um sistema de divisão no espaço, de modo que não é

Detalhes

O grid só existe quando criado, é uma estrutura organizacional, composta por linhas horizontais e verticais que desenham um sistema de divisão no espaço, de modo que não é encontrado organicamente no meio ambiente. André Azevedo combina a vontade de desafiá-lo com a investigação de imagens botânicas, operando em um campo de torção da escrita tradicional e do código visual.

Na mostra Escrita-miragem nos deparamos com um universo singular, apresentado pela primeira vez nessa profundidade, que navega em nuances cromáticas, em que o azul, vermelho, verde e preto adentram o tecido e se transformam em figuração. Vivemos sob o domínio de códigos que se superpõem à experiência do mundo e nos afastam da realidade direta, e é nesse mundo codificado em que/no qual Escrita-Miragem atua. André Azevedo é um organizador de sinais, um semiólogo em ação, sua poética investiga possibilidades plásticas da datilografia, um equilíbrio entre a dureza da máquina e o lírico da representação figurativa floral.

A obra Datilográfica 9 engendra uma abstração e promove a abertura para novos universos. Estar diante dessa peça é como quando há décadas e décadas atrás sintonizávamos as estações do rádio. Um mobiliário/meio de comunicação, o rádio permite sentir as ondas sonoras das estações que transmitem sinais eletromagnéticos em determinadas frequências, em que sintonizamos até encontrar uma frequência dentro do circuito. Datilográfica 9 é o tuning da exposição, nos convoca a adentrar nessa frequência e apreciar uma apreensão poética do mundo codificado.

Azevedo sintoniza a partícula mínima que é uma letra, parte da palavra imagem e a decompõem, recompõe, refaz, reconstrói, e a transforma em imagem. As obras em tecido de algodão não possuem moldura, as laterais esticadas em chassi de madeira são atreladas à feitura da datilografia, em alguns trabalhos existem pequenas pistas de que a imagem é forjada por caracteres. O revelar de camadas se torna evidente com os papéis carbono, aos quais é possível ver cada letra que atravessou a superfície e se tornou luz, virou partitura visual.

Acerca da escolha das imagens projetadas, as ilustrações retomam a vida e os elementos naturais da terra e foram apropriadas do livro “Historia Natural: Vida de los animales, de las plantas y de la tierra – Botánica”, advinda de coleções enciclopédicas ilustradas, populares nos séculos XIX e XX, em uma vida pré digital. A obra mimetiza a gramática da máquina e, em paralelo, a corrompe poeticamente, abrindo rachaduras no sistema de significação. As flores, galhos, ramagens materializam-se nos Is Ms As Gs Es e Ms em um diálogo ritmado entre a rigidez maquínica e a organicidade efêmera.

As relações com a pintura se estreitaram. Azevedo opera o têxtil com o pensamento pictórico e alarga as possibilidades de tradução de imagem por um retorno ao analógico. Em obras que replicam figuras, ao primeiro olhar, são iguais, mas para a observação mais atenta, elevam-se pequenas discrepâncias de coloração, desenhos que se delineiam de outra maneira, fazendo com que os trabalhos repetidos sejam absolutamente singulares em sua formação.

Utiliza um software que pixeliza a imagem e traduz em código para realizar uma imagem, a tecnologia já existe no campo da estamparia, mas é na tradução imagética que Azevedo a ressignifica, a partir do carbono e do gesto se adiciona individualidade a peça, ao subverter a reprodutibilidade técnica pelo imprevisível. A escrita escapa ao controle e a aura insiste em aparecer. Azevedo apropria-se da mecanicidade do aparelho, deixando a escrita por conta da máquina, instruindo os canais a distribuírem tinta em forma de sinais gráficos, cobrindo a superfície para, depois, encobri-la de maneira que seja apresentado algo imageticamente, produzindo um contraste entre a cor da tinta e da superfície.

A escritura é a ciência das fruições da linguagem, a possibilidade de uma dialética do desejo, de uma imprevisão do desfrute, para Roland Barthes, o texto escrito sempre dá uma prova do desejo: é a própria escritura. O que Azevedo propõe é transbordar a escrita, sua prática concebe pela escritura um espaço de fruição poética e novas formas de percepção imagética.

A abordagem pictórica é tanto matérica como mental. O artista se apoia em pensamentos como de Vilém Flusser, em que a cultura é a tentativa de enganar a natureza por meio da tecnologia, da maquinação. As regras numéricas inventadas pelo ser humano, em abstrato, são capazes de descrever, explicar e até prever a experiência sensorial. Tão poderosos são os códigos que construímos a partir deles versões alternativas da chamada realidade, mundos paralelos, múltiplas experiências do aqui e agora. Nesse entendimento, todo artefato é produzido por meio da ação de dar forma à matéria seguindo uma intenção, a manufatura corresponde ao sentido estrito do termo in + formação, dar forma a algo – na poética de Azevedo, de traduzir letra em imagem.

O aparelho se torna não apenas um dispositivo mecânico, mas uma entidade complexa, um compasso entre tecnologia, cultura e a humanidade. A intervenção/interação tecnológica organiza e transforma a realidade e a arte, modulando novos modos de vivência. Ao datilografar, Azevedo organiza sinais gráficos e os desenha, deixando a ação e o pensamento em completa coesão.

A máquina de escrever atua como mediadora entre a natureza e a cultura, criando uma outra camada de complexidade na relação entre o artista e o espectador. Esse aparelho também influencia a comunicação, criando novas formas de expressão e interpretação. Nesse sentido, a tecnologia não é apenas um meio de transmissão de informação, é também um sistema que molda o significado e a mensagem. A prática poética de Azevedo, além de orientar os pensamentos, atua de forma direta no encontro com o outro, sendo apenas quando uma obra escrita encontra o outro que ela alcança sua intenção, uma espécie de ato criador.

Ao investigar diversas possibilidades plásticas da datilografia sobre o suporte têxtil, gera imagens a partir da tipografia, em que cada algarismo imprime sua marca na superfície, com manchas de diferentes intensidades. Nessa lógica de operação, André encontra um possível destino para a escrita no processo de transformar a tipografia em textura e a escrita em imagem. Reconfigura a datilografia em forma visual, adicionando corpo de matéria ao fugidio.

Escrita-Miragem é uma tentativa de capturar o que se dissolve, do movimento de se aproximar e se afastar para decifrar o desenho que atravessa o carbono e se pigmenta na tela, elaborando uma superfície simbólica. É dessa forma que o artista recupera um possível destino para a escrita, híbrida, técnica e sensível, em que o código provoca e projeta um futuro para a escrita a partir da visualidade. Futuro esse que é indisciplinado, e sobretudo, dinâmico. André Azevedo decodifica um futuro do passado.

Mariane Beline e Luana Rosiello

Serviço

Exposição | Escrita-miragem

De 27 de maio a 26 de julho

Segunda a sexta, 10h às 19h, sábado, 10h às 15h

Período

15 de maio de 2025 10:00 - 19 de julho de 2025 19:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

Simoes de Assis Curitiba

Alameda Dr. Carlos de Carvalho, 2173a - Batel Curitiba - PR

Detalhes

Temos o prazer de anunciar SPECTRUM, exposição individual de Siwaju no Prédio 11 d’A Gentil Carioca, no Rio de Janeiro. A prática escultórica da artista investiga as relações entre tempo e

Detalhes

Temos o prazer de anunciar SPECTRUM, exposição individual de Siwaju no Prédio 11 d’A Gentil Carioca, no Rio de Janeiro. A prática escultórica da artista investiga as relações entre tempo e ecologias diversas. A partir do reaproveitamento de peças de aço — doadas, coletadas e recicladas em visitas frequentes a centros de reciclagem —, suas obras estabelecem um vínculo direto com o pensamento tridimensional brasileiro. Suas esculturas articulam matéria e Cosmos, energias visíveis e invisíveis, objeto e entorno, corpo escultórico e espaço, organizando-se em uma temporalidade espiralada, em constante fluxo de expansão e retrospecção, que ativa saberes afrodiásporicos.

“Desdobram-se pelo espaço ‘famílias de obras’ interligadas, cada uma com gramáticas e gestos próprios, mas todas atravessadas pelo desejo de criar zonas de interferência onde passado e futuro, beleza e libertação coexistem em tensão criativa. Como uma ferreira do século XXI, Siwaju não molda o aço, mas negocia com seus espectros: as soldas nascem como costuras entre tempos, as superfícies polidas devolvem reflexos desobedientes, os sussurros da matéria, sugere a artista, nos levam a fuga da lógica industrial.” — aponta a curadora Nathalia Grilo, autora do texto de apresentação da mostra, que fica em cartaz até 9 de agosto de 2025.

Serviço

Exposição | Spectrum

De 24 de maio a 09 de agosto

Segunda a sexta, das 12h às 18h

Sábado, das 12h às 16h (com agendamento prévio)

Período

24 de maio de 2025 12:00 - 9 de agosto de 2025 18:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

A Gentil Carioca

Rua Gonçalves Lédo, 17 - Centro, Rio de Janeiro - RJ, 20060-020

Detalhes

A Gentil Carioca tem o prazer de anunciar Desde sempre o mar, exposição individual da artista Mariana Rocha no prédio 17 d’A Gentil Carioca Rio de Janeiro. Inspirada pela vastidão marítima

Detalhes

A Gentil Carioca tem o prazer de anunciar Desde sempre o mar, exposição individual da artista Mariana Rocha no prédio 17 d’A Gentil Carioca Rio de Janeiro. Inspirada pela vastidão marítima e pelos mistérios da vida microscópica, Rocha mergulha em um universo onde as fronteiras entre ciência, mito e arte se dissolvem. A mostra reúne pinturas inéditas que transitam entre figuração e abstração, evocando formas orgânicas como raízes, cílios, braços e membranas — elementos que se desdobram como símbolos da origem e da continuidade da vida.

Nas palavras do historiador da arte e curador Renato Menezes, que assina o texto de apresentação da mostra, “Mariana Rocha trapaceia a escala e, assim, a própria pintura parece se tornar, para a artista, um meio de reequacionar os mínimos essenciais da vida. Partícula e todo, célula e organismo, gota e oceano renegociam suas ordens de grandeza bem diante de nossos olhos. Não é por acaso que sua pesquisa se volta para o mar: foi lá, nessa vastidão imensa e profunda, que as mais simples formas de vida começaram a aparecer. Mas, como sempre, o mínimo é também o máximo: barroca, dramática, misteriosa e vibrante, sua pintura metaboliza o mundo, para ver, de sua parte mais íntima, obscura, o que de mais superficial ele pode revelar.”

Serviço

Exposição | Desde sempre o mar

De 24 de maio a 09 de agosto

Segunda a sexta, das 12h às 18h

Sábado, das 12h às 16h (com agendamento prévio)

Período

24 de maio de 2025 12:00 - 9 de agosto de 2025 18:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

A Gentil Carioca

Rua Gonçalves Lédo, 17 - Centro, Rio de Janeiro - RJ, 20060-020

Detalhes

Inspirada em trabalho de Dorothea Tanning, mostra marca nova etapa do espaço expositivo Anexo, mais um passo na trajetória de vanguarda da galerista Marilia Razuk, há mais de três

Detalhes

Inspirada em trabalho de Dorothea Tanning, mostra marca nova etapa do espaço expositivo Anexo, mais um passo na trajetória de vanguarda da galerista Marilia Razuk, há mais de três décadas em atuação

A Galeria Marilia Razuk, inaugura uma programação de projetos para o seu espaço localizado no número 62 da Rua Jerônimo da Veiga, que passa a se chamar Anexo Galeria Marilia Razuk. Para marcar essa nova fase, Razuk acolhe a exposição “Sala de Jantar”, com a proposta de exibir obras em um contexto que remete ao ambiente que lhe dá nome.

Com referência ao trabalho Hôtel du Pavot, Chambre 202 (1970-1973), da artista e poeta estadunidense ligada ao Surrealismo Dorothea Tanning, a consultora de arte Cristina Tolovi e a curadora Luana Fortes concebem a mostra se aproximando dos aspectos velados dos espaços domésticos. Elas apresentam obras de artistas e designers, não se apegando a separações entre essas duas esferas da criação. Como conta Tolovi: “A proposta é uma exposição em que diferentes linguagens dialoguem, por meio de uma diluição de fronteiras entre design e artes visuais.”

Luana Fortes destaca: “A mostra nasce de trabalhos de artesãos-artistas-criadores-designers que formam um conjunto de diferentes linguagens e formas de expressão, procurando desestabilizar o que se entende por obra de arte e objeto, guardando tensões do próprio sistema artístico e também das relações fora dele.”

Diferentemente do que vem à mente quando se escutam as palavras “Sala de Jantar”, a mostra tem o intuito de, assim como o trabalho de Tanning, apresentar essa “ambivalência, esse ‘desconforto’ gerado pela separação entre o que está vivo e o que parece imóvel”, nas palavras de Luana, que segue: “Assim, a mostra reúne artistas de diferentes trajetórias e formas de expressão para compor um ambiente que remete a um espaço preparado para o encontro, mas também atravessado por tensões e gestos de controle.”

A galerista, Marilia Razuk, concorda e completa: “A partir desta exposição, buscamos abrir portas para novas ideias, formatos e narrativas curatoriais. Queremos trazer um olhar fresco, sem os vícios que são normalmente adquiridos ao longo dos anos, assim como acolher práticas experimentais e perspectivas inovadoras.”

O trabalho de Fernanda Pompermayer está entre os destaques da mostra. ‘Anúncios cósmicos’, uma obra inédita da artista curitibana, apresenta formas inusitadas por meio transformação e combinação de diferentes materiais, entre os quais estão cerâmica esmaltada, vidro, resina, ouro e madrepérola. Outro nome importante da exposição é o artista visual Daniel Jorge, que exibe trabalhos como ‘Ancestral’. Sua pesquisa se debruça sobre o senso de pertencimento e novas imagens de identidade ao trabalhar com materiais fundamentais para o imaginário afrodiaspórico, como a rocha pedra sabão.

A pintura “Sem retorno ao paraíso” marca a presença de Giulia Bianchi em “Sala de Jantar”. A artista vem desenvolvendo estratégias que possibilitam investigar novas possibilidades de percepção que vão além do óbvio, alterando a escala visual, seja devido aos traços e texturas implícitas em suas pinturas, seja devido à sinestesia provocada por elas. Ana Dias Batista, por sua vez, traz para a exposição trabalhos como “O ovo e a concha”. A prática artística de Ana Dias Batista frequentemente envolve a apropriação de objetos do cotidiano, reorganizando-os de maneira a questionar suas funções originais e provocar novas interpretações.

Serviço

Exposição | Sala de Jantar

De 27 de maio a 26 de julho

Segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h, sábado, das 11h às 15h

Período

27 de maio de 2025 10:00 - 26 de julho de 2025 19:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

Galeria Marilia Razuk

Rua Jerônimo da Veiga, 62 – Itaim Bibi, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

Porto Alegre respira arte com seu mais importante festival. A 14ª Bienal do Mercosul ocupa espaços e ruas e ganha novos ares, imagens e texturas no Centro Histórico com

Detalhes

Porto Alegre respira arte com seu mais importante festival. A 14ª Bienal do Mercosul ocupa espaços e ruas e ganha novos ares, imagens e texturas no Centro Histórico com a inauguração da exposição “Poéticas do Fio – Tramas Nossas” neste sábado, 24 de maio, das 14h às 16h30 na Galeria Duque. A mostra integra o Projeto “Portas para a Arte” da Bienal, que também ocupa a Rua Duque de Caxias em frente à galeria com a instalação “A Arte Conecta”. A curadoria é de Daisy Viola e a exposição fica no espaço até o dia 12 de julho. Entrada franca.

A Galeria Duque ainda oferece uma imersão nas obras de grandes mestres do Brasil com um dos mais completos acervos do Estado. Na mostra “Poéticas Daqui” é possível conferir produções de nomes como Iberê Camargo, Carlos Scliar, Carlos Vergara, Di Cavalcanti, Leopoldo Gotuzzo, Danúbio Gonçalves, Cândido Portinari, Siron Franco, Burle Marx, Anita Malfatti, Ruth Schneider, Maria Lídia Magliani, Frans Krajcberg, Alice Soares, Márcia Marostega, Nelson Jungbluth, Tarsila do Amaral, Gelson Radaelli, Antonio Bandeira, Oscar Crusius, Fernando Baril, Glênio Bianchetti, Glauco Rodrigues, João Luiz Roth, Ione Saldanha, entre outros.

A mostra “Poéticas do Fio – Tramas Nossas” apresenta produções de quatro artistas que utilizam fios e/ou tecidos como suporte ou meio de expressão para sua atividade: Daisy Viola, Fernando da Luz, Fernando Lima e Rosane Morais. “A utilização do fio e do tecido no fazer artístico dialoga com questões sociais e culturais a partir da escolha de materiais e técnicas, como costura, bordado, crochê ou tricô, que fazem parte da história de vida de muitos de nós, das memórias, principalmente femininas, das nossas avós e mães. Assim, o uso de técnicas da artesania tradicional acaba sendo um ponto de encontro entre a tradição e a contemporaneidade”, explica a curadora Daisy Viola.

Já quem passar pela Rua Duque de Caxias vai ter um outro tipo de contato com a arte, mas que também envolve fios e tramas. É a instalação “Arte Conecta”, produzida pelos artistas Roberto Freitas, Adriana Leiria e Ronaldo Mohr. A obra levou dois meses para ser montada e expõe 50 metros de material reciclado, incluindo itens como estofarias e PET, em uma manifestação artística que liga à Galeria Duque ao outro lado da rua e que comprova que a arte é democrática e pode estar presente nos mais diversos espaços.

Serviço

Exposição | Poéticas Daqui

De 24 de maio a 12 de julho

Segunda a sexta, das 10h às 18h, sábados, das 10h às 17h

Período

28 de maio de 2025 10:30 - 4 de agosto de 2025 19:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

Galeria Duque

Duque de Caxias, 649 – Porto Alegre - RS

Detalhes

A Nara Roesler São Paulo tem o prazer de convidar para a abertura da exposição “Sangue Azul”, com novos e inéditos trabalhos de Marcos Chaves. As obras são resultado

Detalhes

A Nara Roesler São Paulo tem o prazer de convidar para a abertura da exposição “Sangue Azul”, com novos e inéditos trabalhos de Marcos Chaves. As obras são resultado de uma pesquisa iniciada em 2013, em que o artista imprimiu em tapetes fotografias que fez de tecidos variados da Coleção Eva Klabin, dentro do 17º Projeto Respiração, na Fundação Eva Klabin, no Rio de Janeiro. Na grande sala de pé direito duplo, no lado esquerdo da galeria Nara Roesler, Marcos Chaves vai criar um ambiente imersivo com baixa iluminação, e foco nos tapetes pendurados nas paredes, todos produzidos em 2025. As dimensões das obras variam de 200 x 266 cm a 150 x 112,5 cm. Cobrindo todo o chão estará um carpete de 5,90 m x 8,39m, versão em grande escala de uma fotografia de 2013, feita de um veludo da Coleção Eva Klabin. Os tapetes nas paredes, em tons de vermelho, reproduzem as fotografias feitas pelo artista do chão acarpetado de locais históricos europeus, como o Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, construído em Roma, no século 16; a escadaria que leva ao único trono existente de Napoleão Bonaparte (1769-1821), no Castelo de Fontainebleau, na França, residência dos reis franceses, e que data dos primórdios do século 12; e a Ópera Garnier, projetada durante o reinado de Napoleão III (1808-1873), o décimo-terceiro palácio a abrigar a Ópera de Paris, fundada por Luís XIV.

“Gosto muito da ideia de degradê, da cor que vai sumindo, e de seu significado em francês também de degradado, coisa gasta, decadente. Com o uso ao longo do tempo, é possível ver nesses tapetes europeus suas várias camadas, em que a trama sobressai e forma um grid. Também ficam visíveis marcas do peso sobre o chão em que o tapete está colocado, formando baixos-relevos. Essa ideia de coisa gasta e a geometria que surge são o que gosto nesse trabalho, que acaba por quase ser uma homenagem à pintura, como se eu estivesse pintando com a fotografia e o pelo do tapete”, conta Marcos Chaves. Alguns trabalhos criam uma perspectiva “ao contrário”, como o que traz os degraus para o trono de Napoleão, e que estará na fachada da galeria, na vitrine.

“OUR LOVE WILL GROW VASTER THAN EMPIRES”

Na primeira sala da exposição, Marcos Chaves vai mostrar três objetos, também na cor vermelha. O primeiro é “Our Love Will grow vaster than empires” (2025), verso do poeta inglês Andrew Marvell (1621–1678) inscrito em um pedaço de veludo e fincado na parede por um canivete suíço. A obra é derivada de um trabalho de 1991, “MessAge”, com canivete e plástico. Os dois outros trabalhos são “readymade”, de 1992 – a bolsa “Jaws”, descoberta por Marcos Chaves emuma feira tipo “mercado de pulgas”, e “Sem título”, um par de sapatos de salto alto encontrado na rua, em uma áreafrequentada por travestis.

O texto crítico é de Ginevra Bria,curadora com vinte anos de trajetória, dedicada a examinar as artes moderna e contemporânea no Brasil. Ela é professora-assistente na Unicamp, onde finaliza sua dissertação iniciada há seis anos para seu PhD em História da Arte na Rice University, em Houston, EUA – “The NoncolorofIndigeneity. Na Art History of Scientific Racism in Brazil, 1865-1935”.Em seu texto sobre a exposição de Marcos Chaves na Nara Roesler São Paulo ela enfatiza: “Em total admiração pela prática da pintura, que Chaves nunca abordou e formalizou, ‘Sangue Azul’ entrelaça fotografias, instalações e esculturas”. “Mas, como eixo expositivo, a fotografia toma emprestado os títulos das obras às contradições de supremacia da nobreza, da política e das uniões de razão de ser históricas (citando espaços de poder como Fontainebleau, Pamphilij e Garnier”. GinevraBria destaca ainda que “neste projeto, entre o lento apagamento das dimensões verticais e horizontais, cada elemento representado, ou ampliado, é hipostasiado num movimento temporal, enquanto a nobre dinâmica dos vermelhos é intemporal. E enobrecida”.

Serviço

Exposição | Sangue Azul

De 07 de junho a 16 de agosto

Segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h, sábado, das 11h às 15h

Período

7 de junho de 2025 10:00 - 16 de agosto de 2025 19:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

Galeria Nara Roesler - SP

Avenida Europa, 655, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

O Centro MariAntonia da USP inaugura, no dia 7 de junho, a partir das 11h, a exposição O silêncio da tradição: pinturas contemporâneas, organizada por Rodrigo Naves, referência na

Detalhes

O Centro MariAntonia da USP inaugura, no dia 7 de junho, a partir das 11h, a exposição O silêncio da tradição: pinturas contemporâneas, organizada por Rodrigo Naves, referência na crítica e no ensino de história da arte no Brasil. A mostra apresenta obras de doze artistas visuais emergentes, participantes de um grupo de estudos conduzido por Naves desde abril de 2024. A visitação acontece de terça a domingo, e feriados, das 10 às 18 horas, com entrada gratuita.

Com encontros semanais voltados à história da arte, o grupo é formado, em sua maioria, por artistas com trajetória ligada ao curso Pintura: prática e reflexão, ministrado por Paulo Pasta, um dos nomes centrais da pintura contemporânea brasileira.

Idealizada por Naves, a exposição tem como eixo a reflexão sobre a importância da história da arte na formação artística e sobre as distintas formas com que cada artista lida com o legado da arte e os desafios da contemporaneidade.

Participam da mostra os artistas Beatrice Arraes, Beatriz Buendia, Bruno Neves, Daniel Tagliari, Guilherme Gallé, Helen Scheunemann, Jesus José, Joji Ikeda, Lucas Rubly, Luiz83, Miguel Mori e Rafael Kamada. A produção conta ainda com a colaboração de Beatriz Almeida e Gabriel San Martin, pesquisadores que também integram o grupo de estudos.

A programação da mostra inclui conversas com nomes relevantes da crítica e da arte contemporânea brasileira, como Paulo Pasta, Lorenzo Mammì, Taisa Palhares, Antonio Gonçalves Filho, Rodrigo Naves, Alberto Tassinari e Bruno Dunley, além de visitas guiadas com os artistas e oficinas educativas. A programação completa estará disponível no site do Maria Antonia.

O organizador

Rodrigo Naves é crítico, historiador da arte e professor, com doutorado em Estética pela Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas (FFLCH) da USP. Publicou ensaios e artigos em diversas revistas, jornais e catálogos brasileiros e do exterior, analisando obras de artistas modernos e contemporâneos. Foi editor em diversos veículos de imprensa, bem como publicou diversos livros. Há mais de 20 anos ministra um curso livre de história da arte.

Os artistas

Beatrice Arraes, Beatriz Buendia, Bruno Neves, Daniel Tagliari, Guilherme Gallé, Helen Scheunemann, Jesus José, Joji Ikeda, Lucas Rubly, Luiz83, Miguel Mori e Rafael Kamada

Serviço

Exposições | O silêncio da tradição: pinturas contemporâneas

De 7 de junho a 28 de setembro

Terça a domingo, e feriados, das 10h às 18h

Período

7 de junho de 2025 10:00 - 28 de setembro de 2025 18:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

Centro MariAntonia – Edifício Rui Barbosa

Rua Maria Antônia, 294 – Vila Buarque – São Paulo, SP

Detalhes

Com curadoria de Daniela Labra, a mostra Primavera Democrática reúne um conjunto de fotografias e vídeos de ações realizadas entre 2017 e 2025 em diversas cidades ao redor do

Detalhes

Com curadoria de Daniela Labra, a mostra Primavera Democrática reúne um conjunto de fotografias e vídeos de ações realizadas entre 2017 e 2025 em diversas cidades ao redor do mundo, reafirmando a relevância e a consistência da obra de Galindo no cenário da arte performática contemporânea.

Como parte da programação, a artista realiza ainda uma performance inédita na Praça da Harmonia, região central da cidade, no dia 3 de junho, terça-feira, a partir das 10h. A ação, que leva o nome da exposição, propõe uma reflexão sobre as persistentes e alarmantes taxas de violência contra a mulher — mesmo em contextos considerados democráticos e institucionalmente estáveis.

Nascida em 1974 na Cidade da Guatemala, onde vive e trabalha, Regina José Galindo desenvolve uma obra profundamente marcada pelas violências estruturais da sociedade latino-americana, com foco em temas como os direitos humanos, o feminicídio, a herança colonial e as desigualdades sociais. Em 2005, recebeu o Leão de Ouro na 51ª Bienal de Veneza por sua performance “¿Quién puede borrar las huellas?”, na qual percorreu descalça as ruas da capital guatemalteca deixando pegadas de sangue, em protesto contra a impunidade e o passado político violento de seu país. Desde então, vem participando de grandes exposições internacionais, como as Bienais de Veneza, São Paulo, Havana, Sharjah e Istambul, além de ter apresentado seus trabalhos em instituições como o MoMA (Nova York), Tate Modern (Londres), Centre Pompidou (Paris) e Guggenheim (Nova York).

Com uma linguagem artística que utiliza o próprio corpo como instrumento político, Galindo constrói ações impactantes que tensionam os limites entre arte, denúncia e ativismo. Sua produção tem sido fundamental para o debate contemporâneo sobre gênero, violência e os mecanismos de poder nas sociedades latino-americanas.

Seus trabalhos fazem parte de importantes coleções institucionais em todo o mundo, incluindo: Tate Londres (Reino Unido), Foundation Centre Pompidou (França), Museu Solomon R. Guggenheim (EUA), La Gaia Collection (EUA), Universidade de Princeton (EUA), Museu Rivoli (Itália), Daros Foundation (EUA), MEIAC (Espanha), Miami Art Museum (EUA), Ubs, Cisneros Fontanals (EUA), Fondazione Teseco (Itália), Fondazione Galleria Civica (Itália), Mmka (Hungria), Consejería de Murcia (Espanha) e Art Foundation Mallorca (Espanha).

“Primavera Democrática” faz parte do calendário especial de ações e projetos expositivos que celebram os 15 anos da Portas Vilaseca em 2025.

Serviço

Exposição | Primavera Democrática

De 07 de junho a 26 de julho

Terça a Sexta, das 11h às 19h, sábado, das 11h às 17h

Período

7 de junho de 2025 11:00 - 26 de julho de 2025 19:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

Portas Vilaseca Galeria

Rua Dona Mariana, 137, casa 2, Botafogo, Rio de Janeiro - RJ

Detalhes

Com curadoria de Daniela Labra, a mostra Primavera Democrática reúne um conjunto de fotografias e vídeos de ações realizadas entre 2017 e 2025 em diversas cidades ao redor do

Detalhes

Com curadoria de Daniela Labra, a mostra Primavera Democrática reúne um conjunto de fotografias e vídeos de ações realizadas entre 2017 e 2025 em diversas cidades ao redor do mundo, reafirmando a relevância e a consistência da obra de Galindo no cenário da arte performática contemporânea.

Como parte da programação, a artista realiza ainda uma performance inédita na Praça da Harmonia, região central da cidade, no dia 3 de junho, terça-feira, a partir das 10h. A ação, que leva o nome da exposição, propõe uma reflexão sobre as persistentes e alarmantes taxas de violência contra a mulher — mesmo em contextos considerados democráticos e institucionalmente estáveis.

Nascida em 1974 na Cidade da Guatemala, onde vive e trabalha, Regina José Galindo desenvolve uma obra profundamente marcada pelas violências estruturais da sociedade latino-americana, com foco em temas como os direitos humanos, o feminicídio, a herança colonial e as desigualdades sociais. Em 2005, recebeu o Leão de Ouro na 51ª Bienal de Veneza por sua performance “¿Quién puede borrar las huellas?”, na qual percorreu descalça as ruas da capital guatemalteca deixando pegadas de sangue, em protesto contra a impunidade e o passado político violento de seu país. Desde então, vem participando de grandes exposições internacionais, como as Bienais de Veneza, São Paulo, Havana, Sharjah e Istambul, além de ter apresentado seus trabalhos em instituições como o MoMA (Nova York), Tate Modern (Londres), Centre Pompidou (Paris) e Guggenheim (Nova York).

Com uma linguagem artística que utiliza o próprio corpo como instrumento político, Galindo constrói ações impactantes que tensionam os limites entre arte, denúncia e ativismo. Sua produção tem sido fundamental para o debate contemporâneo sobre gênero, violência e os mecanismos de poder nas sociedades latino-americanas.

Seus trabalhos fazem parte de importantes coleções institucionais em todo o mundo, incluindo: Tate Londres (Reino Unido), Foundation Centre Pompidou (França), Museu Solomon R. Guggenheim (EUA), La Gaia Collection (EUA), Universidade de Princeton (EUA), Museu Rivoli (Itália), Daros Foundation (EUA), MEIAC (Espanha), Miami Art Museum (EUA), Ubs, Cisneros Fontanals (EUA), Fondazione Teseco (Itália), Fondazione Galleria Civica (Itália), Mmka (Hungria), Consejería de Murcia (Espanha) e Art Foundation Mallorca (Espanha).

“Primavera Democrática” faz parte do calendário especial de ações e projetos expositivos que celebram os 15 anos da Portas Vilaseca em 2025.

Serviço

Exposição | Terra

De 24 de maio a 26 de julho

Segunda a Sexta, das 10h às 19h, sábado, das 11h às 15h

Período

7 de junho de 2025 11:00 - 26 de julho de 2025 19:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

CLARABOIA

Al. Gabriel Monteiro da Silva, 2906 Jardim América, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A artista Tatiana Blass realiza na Albuquerque Contemporânea exposição individual intitulada “Tornado Subterrâneo”. A mostra ocupa o primeiro piso da galeria e é composta de obras inéditas e algumas já

Detalhes

A artista Tatiana Blass realiza na Albuquerque Contemporânea exposição individual intitulada “Tornado Subterrâneo”. A mostra ocupa o primeiro piso da galeria e é composta de obras inéditas e algumas já exibidas em mostras em outras cidades.

Nome de destaque da arte contemporânea brasileira, a artista explora diferentes linguagens para abordar a incomunicabilidade nas relações interpessoais e a subjetividade do indivíduo diante de um mundo em constante transformação. Para isso, recorre a diversos suportes – pintura, escultura, instalação e vídeos – nos quais explora as dimensões de tempo e espaço de maneiras singulares.

Na série “Meia Luz”, de oito pinturas em grande escala, a artista faz referências a filmes e obras teatrais, construindo cenas e sugerindo narrativas em que prevalece a ambiguidade. As formas e cores, pouco definidas, criam ambientes que questionam as relações entre os personagens e seu estar no mundo.

Duas pinturas de 2×3 metros sobre vidro da série “Teatro de Arena –Tornado Subterrâneo” serão expostas na entrada e no fundo da galeria. A artista aborda o tema da mineração, com paisagens desérticas e figuras minúsculas. Crateras pontuadas por alguns personagens na vastidão do espaço devastado retomam o tema do palco, como em busca por um papel a desempenhar em um teatro de arena e as diminutas possibilidades de ação frente à destruição ambiental. Nesses trabalhos, a luz e a transparência dialogam com a paisagem de fundo, criando um jogo espacial com o entorno.

Os temas da mineração e do espaço cênico adquirem outras formas nas esculturas em bronze, realizadas com tinta e cera, em um processo longo e delicado que evidencia os efeitos da temporalidade sobre a matéria, resultado de um processo de derretimento da cera e da tinta pelo calor sobre a peça metálica. Restam nas obras os vestígios das matérias mais efêmeras, que remetem à temporalidade e à decomposição. As imagens do processo são exibidas em vídeo, revelando o desaparecimento das figuras – ou atores – de cera no cenário criado pela artista, fundindo passado e presente.

A instalação “Metade da fala no chão – Bateria preta” é uma nova versão de um importante trabalho da artista que integra a série com instrumentos musicais. Quatro baterias cortadas em formato de um grande círculo, com bumbos, caixas, surdos e pratos, são preenchidas por cera ou espalhadas pelo chão, ocupando 25 metros quadrados. Novamente, o tema da impossibilidade de comunicação é trazido à tona, desta vez, através do silêncio, imposto com certa violência, um corte radical que emudece e explicita incompletude.

Fazendo uso de varados recursos materiais, as obras frequentemente operam o sentido a partir da sinestesia: o silêncio imposto pela cera, a dimensão tátil das cores, o tempo narrativo sugerido em imagens estáticas, o elemento cênico carregado de subjetividade, a impossibilidade de alcançar o outro nas relações interpessoais. São temas bastante atuais apresentados com rigor formal e uma sensibilidade artística que intrigam e convidam o espectador numa imersão a sensações e questionamentos.

Serviço

Exposição | Tornado Subterrâneo

De 24 Junho a 30 Agosto

Segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h, sábado, das 10h às 13h30

Período

24 de junho de 2025 10:00 - 30 de agosto de 2025 19:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

Albuquerque Contemporânea

Rua Antônio de Albuquerque 885 - Savassi, elo Horizonte - MG

Detalhes

O MIS, instituição da Secretaria da Cultura, Economia e Indústria Criativas do Estado de São Paulo, inaugura a terceira exposição do projeto Nova Fotografia 2025: “Entre sombras encontro luz”,

Detalhes

O MIS, instituição da Secretaria da Cultura, Economia e Indústria Criativas do Estado de São Paulo, inaugura a terceira exposição do projeto Nova Fotografia 2025: “Entre sombras encontro luz”, do fotógrafo Rodrigo Pivas. Com entrada gratuita, a mostra fica em cartaz até o dia 17 de agosto.

A partir da cidade como tema, Rodrigo Pivas elege as feiras livres na capital paulista como territórios de investigação poética e visual. Iniciada em 2021, a série “Entre sombras encontro luz” apresenta o cotidiano das feiras através das cores, detalhes, formas e gestos moldados e realçados pela luz. Num procedimento que acentua o chiaroscuro barroco, Pivas observa como a luz natural, aliada aos toldos e prédios, realiza recortes que enfatizam o contraste entre claridade e sombra. Na exposição, as 27 imagens parecem se fundir à parede, o que intensifica o destaque da luz sobre os detalhes e objetos que, em geral, passam despercebidos.

“Uma vez por semana retorno ao mesmo local. Um mundo de cores, sabores, texturas e sons com os mais variados sotaques, o mais popular comércio de rua da cidade e do país, a feira. Vista não apenas como um ponto de comércio de produtos alimentícios, mas essencialmente enquanto local de encontro e confraternização. Sua capacidade de proporcionar, ao mesmo tempo, a interação social e o intercâmbio cultural entre indivíduos de uma mesma comunidade ou mesmo de comunidades vizinhas. O recorte da luz, banhando seus elementos e personagens, conduz meu olhar nessa jornada, entendendo as diferentes características e unindo suas semelhanças através da fotografia”, diz Rodrigo Pivas sobre sua série fotográfica.

Sobre o Nova Fotografia

O Nova Fotografia é um projeto anual do MIS – instituição da Secretaria da Cultura, Economia e Indústria Criativas do Governo do Estado de São Paulo – que seleciona, através de convocatória aberta ao público, seis novos fotógrafos para uma exposição individual no museu. A seleção fica a cargo do Núcleo de Programação, com supervisão e coordenação da curadoria geral do MIS. São selecionadas séries fotográficas inéditas, de profissionais que se destacam por sua originalidade técnica e estética. Após o período em exposição, as séries escolhidas passam a integrar o acervo do MIS.

Serviço

Exposição | Nova Fotografia – Entre sombras encontro luz

De 01 de julho a 17 de agosto

Terças a sextas, das 10h às 19h, sábados, das 10h às 20h e domingos e feriados, das 10h às 18h

Período

1 de julho de 2025 10:00 - 17 de agosto de 2025 19:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

Museu da Imagem e do Som - MIS

Av. Europa, 158, Jd. Europa São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

Como escreve Neusa Santos Souza, descobrir-se preto vai além do que é visível. É atravessar a experiência de ter a identidade negada, ser confundido em suas perspectivas e submetido

Detalhes

Como escreve Neusa Santos Souza, descobrir-se preto vai além do que é visível. É atravessar a experiência de ter a identidade negada, ser confundido em suas perspectivas e submetido a exigências alheias. Ainda assim, saber-se preto é um ato de reconstrução: buscar, na própria história, sinais de pertencimento e continuidade. Ser preto não é somente uma condição dada, é um vir a ser. Ser preto é tornar-se preto.

Nesta exposição, revisito a parte materna da minha família, composta em sua maioria por mulheres pretas que, como em muitas famílias brasileiras, são o alicerce da criação, da educação, da preservação e da transmissão de valores, saberes e práticas culturais que sustentam a comunidade afrodescendente.

As gravuras, criadas nas técnicas de xilogravura, linoleogravura, fotogravura, gravura em metal e processos híbridos que articulam tradição e tecnologia, são inspiradas em histórias vividas e contadas durante minha criação na cidade de Sumaré, interior de São Paulo: em cenas do cotidiano, no café da manhã, nas festas em família, nos momentos de trabalho e de descanso.

As obras também abordam o sincretismo religioso, entre

tradições de matriz africana e o catolicismo popular, fortemente presentes no âmbito espiritual da família.

Tornar-se Preto: Meus Laços de Família é um ato de

autoconhecimento e de retorno. Um agradecimento simbólico àquelas que me fizeram e me conduziram até este momento em que me encontro como ser.

Serviço

Exposição | Tornar-se Preto: Meus Laços de Família

De 01 de julho a 03 de outubro

Segunda a sexta, das 12h às 17h

Período

1 de julho de 2025 10:00 - 3 de outubro de 2025 19:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

Centro Municipal de Cultura Uberlândia

Praça Prof. Jacy de Assis - s/n - Centro, Uberlândia - MG

Detalhes

Pré-fabricação é um método construtivo em que parte ou todos os componentes de uma construção são produzidos em uma fábrica e, posteriormente, montados no local da obra. A construção

Detalhes

Pré-fabricação é um método construtivo em que parte ou todos os componentes de uma construção são produzidos em uma fábrica e, posteriormente, montados no local da obra. A construção de casa pré-fabricada japonesa, que alia o design à otimização dos materiais, possibilitou maior eficiência ao sistema de construção e contribui para uma maior qualidade de vida aos moradores e à comunidade. A partir de 1º de julho, a Japan House São Paulo traz exemplos dessa inovação nipônica para o andar térreo de sua sede na Avenida Paulista em “Anatomia pré-fabricada: um morar no Japão”. A exposição apresenta o universo das inovadoras construções pré-fabricadas japonesas atuais a partir de um modelo em tamanho real e maquetes. Também compõe a mostra uma linha do tempo com os principais marcos na história das construções pré-fabricadas no Japão, desde os anos 1950 até os dias atuais, desenvolvida especialmente para a JHSP por Yoshikuni Shirai, professor convidado especial da Faculdade de Meio Ambiente e Estudos da Informação da Universidade de Keio e Editor-chefe da revista Sustainable Japan Magazine by The Japan Times.

No espaço expositivo, a curadoria de Natasha Barzaghi Geenen, diretora cultural da JHSP, apresenta parte de uma casa, em escala real, criada pela VUILD. O modelo apresentado faz parte da série NESTING, na qual o próprio cliente consegue projetar sua casa a partir de modelos preestabelecidos que estão disponíveis em um aplicativo e, a partir da madeira processada por meio da fabricação digital, consegue montá-la em colaboração com sua família e amigos. Junto da casa, a exposição apresenta também suas peças, elementos construtivos, separadamente, como se decupasse essa construção, evidenciando sua anatomia.

Além disso, a exposição traz também a maquete da Marebito no ie, outra iniciativa da VUILD que busca revitalizar regiões montanhosas com população em declínio, propondo a construção de alojamentos de propriedade compartilhada, visando a circulação contínua de pessoas nessas áreas, em um modelo de vida que vai além do turismo, mas que não chega a ser uma residência definitiva. O projeto, que utiliza tecnologia de fabricação digital, visa otimizar o uso de recursos florestais locais, utilizando a madeira dessas regiões para a construção da casa e de seus móveis, priorizando o uso da madeira lamelada cruzada (também chamada de madeira CLT), como alternativa ao concreto.

Como exemplo de inovações das casas pré-fabricadas com o foco na segurança, proteção e prevenção de desastres e conforto, a exposição também apresenta um modelo tátil que demonstra um tipo de sistema de isolamento térmico, que reduz a influência da temperatura externa, evita a condensação dentro das paredes e diminui os custos relativos aos sistemas de aquecimento e resfriamento, demonstrando a avançada tecnologia japonesa.

“O objetivo é permitir que o público se familiarize com dimensões de alguns modelos de moradias contemporâneas do Japão, ao mesmo tempo em que pode refletir sobre como essas soluções podem ser adaptadas ao contexto brasileiro. Nossa proposta é fomentar o debate sobre novas formas de construir, incentivando parcerias entre Brasil e Japão para desenvolver modelos cada vez mais sustentáveis de habitação inteligente”, afirma a curadora Natasha.

Já no espaço externo da JHSP, o público é convidado a experimentar alguns elementos inspirados nas habitações tradicionais japonesas, como os cômodos com características flexíveis e personalizáveis, delimitados por portas de correr chamadas de “fusuma” e pisos cobertos por tatames. Crianças e adultos poderão brincar de reconfigurar os espaços com estruturas móveis como uma forma de aprender na prática sobre esses conceitos e vivenciar essa espacialidade. Ainda sobre a exposição, Natasha comenta: “Mais do que uma preocupação com recursos e design, nossa ideia é conectar os visitantes a esse senso de responsabilidade forte que os japoneses têm, de que são parte de um todo e que suas ações devem contribuir para uma melhor condição da sociedade. Esses modelos de habitação mostram a preocupação com o todo, com a comunidade e o meio em que vivem, indo muito além da estética e da mera empatia”.

Ao longo de todo o período expositivo, a JHSP ainda promoverá palestras, seminários e oficinas com temas diversos ligados à sustentabilidade, reuso de materiais e propostas alinhadas com a exposição “Anatomia pré-fabricada: um morar no Japão”. A mostra também integra o programa JHSP Acessível, oferecendo recursos táteis, audiodescrição e vídeo em libras para proporcionar acessibilidade a todos os visitantes.

Serviço

Exposição | Anatomia pré-fabricada: um morar no Japão

De 01 de julho a 12 de outubro

Terça a sexta, das 10h às 18h; sábados, domingos e feriados, das 10h às 19h

Período

1 de julho de 2025 10:00 - 12 de outubro de 2025 18:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

Japan House São Paulo

Avenida Paulista, 52 – Bela Vista, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

Acervo Vivo é um programa que explora o acervo da Almeida & Dale por meio de exposições organizadas por curadores e pesquisadores convidados e internos. As exposições do projeto partem

Detalhes

Acervo Vivo é um programa que explora o acervo da Almeida & Dale por meio de exposições organizadas por curadores e pesquisadores convidados e internos.

As exposições do projeto partem de uma seleção criteriosa e não hierárquica de obras que propõe diálogos entre artistas contemporâneos e de diferentes gerações, transpondo barreiras cronológicas, construindo articulações inusitadas, revelando novas camadas de sentido e promovendo encontros entre tempos e narrativas distintas.

Ao ativar o acervo como um campo de investigação contínua, Acervo Vivo reafirma o compromisso da galeria com a valorização da arte brasileira e global em suas múltiplas temporalidades, contribuindo para sua preservação, difusão e constante reinterpretação.

Acervo Vivo: Vivenciando a transcendência: uma coreografia de pinturas inaugura na quinta, 3 de julho, na Almeida & Dale Caconde 152. Partindo da pintura de Rubens Gerchman, a exposição propõe um percurso vertiginoso por entre pinturas de diferentes períodos e tendências, passando pelo abstracionismo, construtivismo, pop e a pintura contemporânea, constituindo um bailado que convida à uma experiência alucinatória, arraigada nos sentidos e de suspensão dos limites da historiografia tradicional da arte.

Serviço

Exposição | Acervo Vivo – Vivenciando a transcendência: uma coreografia de pinturas

De 03 de julho a 31 de julho

Segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h, sábado, das 11h às 16h

Período

3 de julho de 2025 10:00 - 31 de julho de 2025 19:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

Almeida & Dale Caconde

R. Caconde, 152, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

Luciana Brito Galeria e Galatea Salvador apresentam Regina Silveira: Tramadas, a primeira exposição individual da artista na capital soteropolitana. A inauguração da mostra coincide com a semana da Independência

Detalhes

Luciana Brito Galeria e Galatea Salvador apresentam Regina Silveira: Tramadas, a primeira exposição individual da artista na capital soteropolitana. A inauguração da mostra coincide com a semana da Independência da Bahia, celebrada no dia 2 de julho.

Fruto de uma parceria inédita, a exposição tem curadoria de Adriano Casanova e Tomás Toledo, conta com texto crítico de Ana Maria Maia e reúne obras emblemáticas de Regina Silveira, muitas delas inéditas no Brasil, que sintetizam sua pesquisa em torno do bordado ao longo dos anos. Elemento recorrente na obra de Regina Silveira desde 1999, o uso do bordado em ponto de cruz, entendido como codificação da imagem, remete a uma herança trans-histórica e intercultural, relacionada à própria história remota da alfabetização das mulheres, em sua trajetória de resistência.

Uma grande instalação site-specific é destaque da mostra Tramadas, que acontece no espaço da Galatea em Salvador, localizado no térreo do Edifício Bráulio Xavier, na Rua Chile, a primeira rua do Brasil. Malfeitos, da série dos “bordados malfeitos”, ganha uma reativação inédita adaptada à fachada de vidro da galeria, convidando o público a conhecer mais. A obra, formada por tramas de linhas vermelhas acompanhadas por uma agulha, sem respeitar qualquer ordem de construção, realizada como aplicação de vinil adesivo, permite “janelas” de observação para o espaço interno. Essa obra rememora mais de quinze anos de produção de Regina Silveira sobre a temática do bordado aplicado a espaços arquitetônicos, período no qual algumas obras, mesmo que efêmeras, permanecem no imaginário do público, como Tramazul, que ocupou por alguns meses, desde o final de 2010, a fachada do MASP com bordados de nuvens no céu azul, e a Trapped Pink, quando habitou um ambiente amplo na Trienal Internacional de Artes Gráficas, em Varsóvia, na Polônia, em 2017.

Antes disso, desde 1999, Regina Silveira já investigava a construção de imagens gráficas a partir da codificação das diferentes tramas de bordados. Ao longo dos anos, a artista se apropriou de imagens em revistas de bordados que encontrou ao redor do mundo, como referências para suas criações. Outros trabalhos apresentados na exposição ilustram bem essa trajetória até o presente. Ao fundo da galeria, em paralelo a instalação Malfeitos, a mostra apresenta Dreaming of Blue II (2016), painel em cerâmica com sobrevidrado, em diálogo com a série histórica de gravuras Risco (1999), encomendada na época pela Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo para distribuição a museus brasileiros, apresenta tramas codificadas como uma espécie de véu que deixa transparecer objetos duros, como ferramentas, comparáveis às impressões sobre alumínio, feitas anos depois (serie Tramada, 2015), que parecem aprisionar objetos similares. A exposição também reúne gravuras da série Armarinhos (2002-2003), representando elementos relacionados à prática do bordado, como agulha, botão e alfinete, além das serigrafias Tramada (Pink) (2014) e Blue Skies (2015).

A mostra apresenta, ainda, as maquetes Tramazul (2010) e Casulo (2025), que remetem à ocasião em que Silveira aplicou tramas bordadas, impressas e recortadas em vinil adesivo sobre vários ônibus de linhas municipais que circularam normalmente durante a 16a Bienal Internacional de Curitiba, em 2016.

Serviço

Exposição | Tramadas

De 04 de julho a 11 de outubro 2025

Terça a quinta, das 10 às 19h, sexta, das 10h às 18h e sábado das 11h às 15h

Período

4 de julho de 2025 10:00 - 11 de outubro de 2025 18:00(GMT-03:00)

Local

Galeria Galatea Salvador

R. Chile, 22 - Centro, Salvador - BA

Detalhes

O MAC USP inaugura no sábado, 5 de julho, a exposição Ana Amorim | Mapas Mentais, reunindo cerca de 70 trabalhos da artista em quase quarenta anos de carreira.

Detalhes