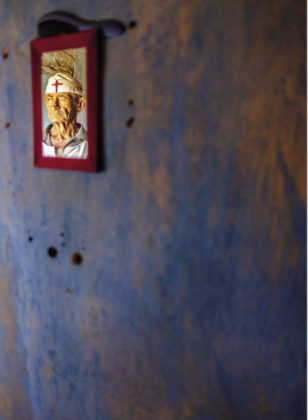

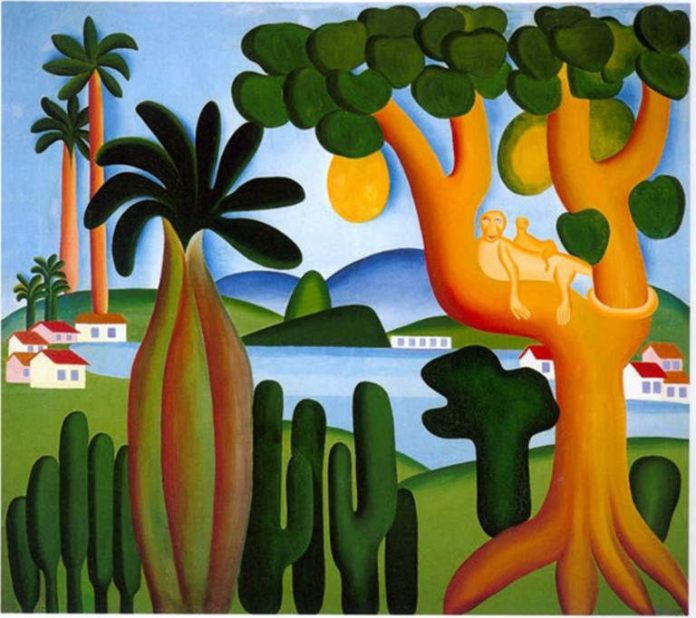

Em Cartão-postal (1929), de Tarsila do Amaral, já o título indica o quanto a artista estava imersa na cultura visual de sua época. No início do século XX, os cartões-postais eram uma mania, carregando em uma de suas faces, imagens fotográficas as mais variadas e, na outra, mensagens interpessoais. Foi tanta a força do cartão-postal naquela época, que se transformou em um elogio: quando alguém se deparava com uma bela imagem, a maneira de prestar-lhe reverência era compará-la a uma pintura ou a um cartão-postal.

Interessante o quanto a pintura de paisagem e o cartão-postal estão associados, mesmo sendo tão distintos, já que a primeira é única, enquanto o segundo é um múltiplo. O que os une, é que parte das fotos de paisagem impressas em cartões-postais replicam esquemas pictóricos prévios, seguindo as estruturas “clássicas” de composição: primeiro plano escuro – contando com elementos vegetais, animais e/ou humanos, que apresentam a cena principal; plano intermediário – normalmente uma superfície líquida (vazia ou com uma ou outra representação); ao fundo, uma cadeia de montanhas e, mais além, o céu.

Desde os pintores viajantes do século XVII, o litoral do Rio de Janeiro foi representado por gravuras, aquarelas ou pinturas a óleo. A partir da fotografia – e de suas possibilidades de reprodução –, o encanto por aquele local ganhou uma visibilidade maior, percorrendo o mundo por meio do serviço de postagem.

Assim, apesar das diferenças de suporte e de produção, o que teriam em comum essas pinturas e fotografias? Todas retratam trechos “pitorescos” do Rio – sendo “pitoresca” uma tradição das artes visuais, teorizada a partir do século XVIII, significando uma paisagem singular, digna de ser pintada. Porém, tal “singularidade” – notada no exotismo das texturas e das formas representadas – dificilmente foge das estruturas paisagísticas “clássicas”, citadas acima. Em Cartão-postal, a artista atualiza aquela estrutura, vista tanto nos mestres do século XVII em diante, quanto nas fotografias dos cartões-postais do Rio: o primeiro plano ocupado pela vegetação exótica, em que sobressaem, à esquerda, uma planta e, à direita, uma árvore, em que descansam um animal e seu filhote. Ambos observam o espectador, chamando sua atenção para o centro da imagem: uma área azul sublinhando o Pão de Açúcar – uma das referências do Rio; na sequência, uma linha de morros verdes e azuis e, enfim, o céu.

***

Com Cartão-postal, Tarsila atualizava, mas mantinha a estrutura pictórica comentada, e a atualização se dava pela síntese das figuras, agregando àquela tradição um esforço de, ao mesmo tempo em que obedece à “verdade” da paisagem, inventa formas que pouco têm de verdadeiras (a vegetação e os animais). Por outro lado, essas formas foram produzidas de maneira a não deixar marcas explícitas da ação da artista sobre a tela. Pelo contrário: houve ali um esforço para banir qualquer índice de manualidade e, portanto, de autoria, como se a pintura à nossa frente fosse, de fato. um cartão-postal.

→ Leia aqui texto de Tadeu Chiarelli sobre os desenhos de Tarsila do Amaral

Esse procedimento assumido por Tarsila logo que chega a Paris, em 1923[1], é devido a seu contato com a pintura de Fernand Léger, que concebia um caráter impessoal para sua produção, para nela emular os produtos da sociedade de massa. Segundo o estudioso norte-americano Kirk Varnedoe, após 1920, Léger:

[…] desenvolveu um realismo geometricamente simplificado, com bordas bem marcadas e essa mudança, com os interesses socialistas que também o motivaram, tornaram o artista atento às formas efetivas dos meios de comunicação de massa. Um anúncio que falasse claramente ao povo parecia ter vindo do povo e era possuidor de uma franqueza que o tornava uma espécie de arte popular. [2]

Embora em 1929 Tarsila seguisse também outros parâmetros, é inegável como ela ainda obedecia aos ensinamentos de Léger, quer nos contornos das formas, quer na impessoalidade procurada, uma referência à cartazística dos anos 1920. No conjunto de pintores protagonistas da cena francesa, Léger era o mais fiel à figuração da realidade moderna, longe do “cubismo integral” e hermético de Gleizes (que Tarsila também contactou) e da poética então oscilante de Picasso (ora cubista, ora “clássico”). Léger era o artista comprometido em transpor para a pintura a modernidade da metrópole, apropriando-se, não apenas da estética do cartaz, como também da estética das vitrines dos magazines parisienses[3]. Outra lição que Tarsila manteve de Léger foi o entendimento da pintura de cavalete como um mecanismo equilibrado entre o real e o “imaginado”:

A obra plástica é o “estado equívoco” desses dois estados, o real e o imaginado. Encontrar o equilíbrio entre esses dois polos, esta é a dificuldade, mas cortar a dificuldade ao meio e considerar só um dos polos, fazer abstração pura ou imitação, é, na verdade, muito fácil, é evitar o problema na sua totalidade.[4]

Tarsila, apesar das outras referências, preservou esse equilíbrio buscado por Léger, constituindo uma iconografia moderna e, ao mesmo tempo, “brasileira”, como desejavam seus amigos modernistas. Mas não foi apenas esse aspecto que ela herdou do pintor francês. Como dito, muitas das estratégias do artista foram utilizadas por Tarsila, que promoveu um esforço de adaptação daqueles procedimentos à realidade da pintura que queria fazer no Brasil[5].

A adesão de Léger à plástica dos meios de comunicação de massa é um fenômeno visível após o início da década de 1920. Antes, embora já interessado no ambiente das metrópoles, ele mantinha-se fiel a integrar à pintura elementos percebidos nessa nova paisagem, mantendo como protagonista sua subjetividade de espectador. Aquela subjetividade de quem, ainda que assustado, assiste ao turbilhão da metrópole, ao atropelo dos sinais que a regem. Nas pinturas dessa época são nítidas as bordas demarcadas das formas, mas subsiste ainda o interesse em relacioná-las entre si e entre elas e a cidade, da qual são uma representação. Este tipo de agenciamento já não é possível perceber em O sifão (1924), em que são raras as áreas em que se percebe uma relação de continuidade de uma forma quando interceptada por outra. Em Composição com quatro chapéus (1927), ocorre o mesmo: as formas se sobrepõem, sem estabelecer relação espacial, como se integrassem uma colagem, e não uma pintura: uma forma cobre a outra, não havendo interação entre elas, com exceção daquela que parece uma alusão a uma caixa – da qual se vê apenas uma de suas laterais e o topo.

Em Cartão-postal, de Tarsila, também as formas demarcadas se sobrepõem como em uma colagem, dificultando que se fale em planos – primeiro plano, plano intermediário, último plano etc. Nela, as formas estão recortadas e justapostas, quando não “coladas” umas sobre as outras. Essa estratégia, dispensável lembrar, reitera o caráter bidimensional não apenas dessa pintura, mas da maioria daquelas realizadas pela artista nos anos 1920.

***

É de 1923 a pintura Rio de Janeiro[6]. A imagem assemelha-se a Cartão-postal, produzida cinco anos depois: a cidade é a mesma, o ponto de vista escolhido do mesmo modo privilegia o Pão de Açúcar. O esquema também é igual: primeiro plano mais escuro, plano central com água e o morro e, ao fundo, montanhas e o céu azul. A diferença está no tratamento. Rio de Janeiro, que poderia chamar-se “cartão-postal”, replica a tradição fotográfica ao repetir a tradição da pintura, e só se difere da obra de 1929 pela maneira como foi pintada: se em Cartão-postal as formas recortadas, justapostas e/ou sobrepostas, enfatizam o caráter planar do suporte, em Rio de Janeiro, o tonalismo que acentua a simulação da profundidade e o uso de pinceladas aparentes – que, por sua vez, registram a “subjetividade” da artista –, demonstram que a produção dessa tela antecede o contato de Tarsila com a obra de Léger, ainda em 1923.

***

Segundo Aracy Amaral, 1923 foi um ano agitado para a artista[7]. Chegando em Paris no final de 1922, entre festas, concertos e banquetes, Tarsila passa janeiro e fevereiro entre Portugal e Espanha. Entre julho e final de setembro, ela e Oswald de Andrade viajam pela Itália e, em dezembro, ela retorna ao Brasil. Assim, dos doze meses, Tarsila conseguiu frequentar os ateliês de André Lhote, Léger e o de Albert Gleizes, durante mais ou menos seis meses[8]. A autora afirma que Tarsila teria frequentado o ateliê de Lhote durante três meses[9], portanto, acredita-se que essa experiência ocorreu entre março e maio de 1923, antes da viagem para a Itália, e após ida para Portugal e Espanha. Ainda segundo Amaral, Tarsila vai três vezes ao ateliê de Léger[10] e com Gleizes realiza “dezenas de esboços e exercícios de estrutura do quadro… em menos de um mês e meio…”[11].

***

Se para Aracy Amaral, a dimensão teórica dos ensinamentos de Gleizes, seria “a que mais a marcaria no futuro”[12], é supõe-se que Léger e sua produção foram os mais relevantes para Tarsila naquele ano, e aqui surgem as pinturas A negra e Caipirinha, ambas de 1923. Independente de Tarsila ter sido ou não sua aluna[13], interessa é que Lèger, já em 1923, tornou-se um parâmetro para ela.

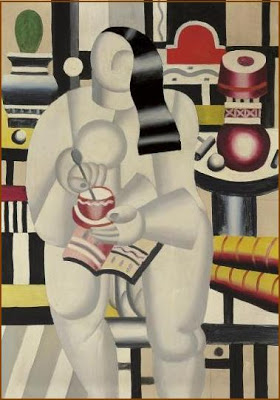

Brigitte Hedel-Samson, ao demonstrar a importância de Léger para a produção de Tarsila, lembra que ele “pedia a seus alunos que explorassem temas baseados em suas próprias pinturas”, e chama a atenção para duas obras de Tarsila: – Estudo (Academia n.1) – baseado na pintura A xicara de chá, de 1921, de Léger, e O pescador, 1925c., que lembraria, segundo a autora, a série Os almoços, do pintor francês.[14].

Além de Estudo (Academia n.1), seria possível atentar igualmente para outra obra de Tarsila, em que a presença de A xicara de chá se faz notar, Estudo (Academia n.2). É notável a semelhança entre as duas academias e a pintura de Léger: em um fundo geométrico e bidimensional – onde formas reconhecíveis são aplicadas como colagens – também é sobreposta uma sintética figura feminina, que apenas se destaca do fundo pela delimitação do contorno e pela cor que preenche a área que ocupa. No caso da obra do francês, a figura da mulher é fria, metálica; nas pinturas da brasileira, tons amarronzados cobrem as figuras femininas. Dentro do conjunto de suas obras dos anos 1920, A xicara de chá talvez seja um dos melhores exemplos de como Léger estava interessado na estética do cartaz, emulando seu caráter bidimensional, e seu apego a superfícies que remetiam aos produtos industrializados, lisos, impessoais.

Assim, interessam as transformações que Tarsila produziu naquele novo parâmetro que seguiria dali para a frente. Nota-se nas duas pinturas a obediência à bidimensionalidade e à estratégia do procedimento da colagem na organização do espaço. No entanto, se em Léger o uso de cores quentes é parcimonioso – para não quebrar o clima frio do todo –, em Tarsila nota-se o abuso das mesmas, tanto no espaço geometrizado que cria ao lado das figuras, quanto nelas próprias. Nessas últimas, sublinhe-se igualmente o quanto o uso de tons diversificados de marrons serve como alusão a um tipo determinado de figura feminina, uma mulher não europeia, negra.

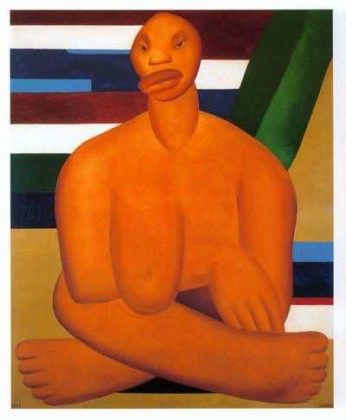

Não é à toa que uma das pinturas mais emblemáticas produzidas por Tarsila do Amaral naquele ano de 1923, A negra, possa ser examinada tendo como pano de fundo as três pinturas acima comentadas. A negra deve ser entendida como saída diretamente do esforço de Tarsila em apreender a estética legeriana e, ao mesmo tempo, impregná-la de um sabor original, “brasileiro”: a mulher negra – caracterizada não apenas pela cor descritiva do corpo, mas também pelo traços de caricatura do rosto – está como que colada em um fundo geometrizado simulando uma paisagem. Afinal, além da forma que lembra uma folha de bananeira `a direita, a mulher parece sentada em uma praia, com uma faixa de mar também à direita. À sua esquerda, ao “fundo”, referências à terra e ao ar.

Esse esforço de Tarsila em abrasileirar a poética de Léger, trazendo para as suas pinturas a relação direta entre plano pictórico e a lógica da colagem, determinará todo o seu esforço em constituir uma arte moderna, mas com supostos índices de “brasilidade”.

Alguém poderia objetar, argumentando ser impossível essa “influência” de Léger em A Negra pelo fato de que Tarsila, em sua primeira ida ao ateliê do artista, já ter levado consigo a obra para mostrá-la ao artista. Ora, o fato de Tarsila ter frequentado por pouco tempo o ateliê de Léger, não significa que ela só tenha entrado em contato com sua produção após aquela visita. Pelo contrário: com uma visão pragmática sobre quem era quem naquela Paris tão sedutora, Tarsila com certeza procurou Léger (como a Lhote e Gleizes) porque ele era, naquele momento, um dos “ai, Jesus!” da cena parisiense. E mais: já ter conhecido Léger antes da primeira visita ao seu ateliê não significava ter sido a ele apresentada formalmente em algum banquete elegante, mas sim, e sobretudo, ter tido acesso à sua produção mais recente em salons e/ou exposições públicas, tê-la estudado a partir dessas visitas e – por que não? – ter plasmado a fatura pictórica do artista mais experiente às suas expectativas em produzir uma pintura moderna e “brasileira”. Daí Tarsila ter pintado A Negra em Paris e a ter levado consigo em sua primeira visita a Lèger. Daí, a melhor explicação para o fato de Léger ter gostado tanto dessa obra e desejado que seus alunos a admirassem. Afinal, A negra fora produzida à semelhança de suas obras mais atuais![15]

Dentre as estratégias usadas por Tarsila para inserir sua produção no âmbito parisiense, mantendo-a “brasileira”, integra-se também A caipirinha. Espécie de A negra, só que vestida, a figura se encontra em uma paisagem em que são mais evidentes do que na pintura anterior, os elementos do cenário onde ela está situada – pois menos abstraídos –, e também as tonalidades que naturalizam a composição. O lago, as paredes, a vegetação, o céu, assim como a moça que segura a folha, são tratados de maneira descritiva, não deixando dúvidas quanto ao que são. Porém, não menos importantes são seus procedimentos “modernos” e que, caso fossem outros, Caipirinha seria uma pintura naturalista: as formas que preenchem o campo parecem recortadas e justapostas como um trabalho de recorta e cola – o que enfatiza sua condição bidimensional. Tal procedimento, por outro lado, realça um certo humor lúdico, presente na pintura. Refiro-me à maneira como Tarsila trabalha a área centro esquerda da tela. Ao colocar formas retangulares sobre as representações da árvore, da casa e do gramado (formas que representariam janelas e uma cerca), a artista o faz como se as colasse de maneira “errada” (sobretudo o retângulo sobre a casa e a árvore), reforçando o caráter bidimensional do quadro e fazendo pendant com outra forma retangular – essa representando uma porta no canto direito.

***

Desse seu período inicial, destacam-se ainda duas obras cujo assunto é a cidade de São Paulo. Refiro-me às pinturas São Paulo e São Paulo (Gazo), ambas de 1924. Como já chamou a atenção de muitos, nelas surpreende a ausência mais emblemática da modernidade: a multidão

A São Paulo de Tarsila é destituída de qualquer referência à figura humana (a não ser que se queira enxergar nas bombas de gasolina presentes nas duas obras alguma referência cifrada a seres humanos). Em São Paulo são observados o mesmo esquema das outras paisagens comentadas: um primeiro plano ocupado por árvore, gramado, chão e as bombas de gasolina; um plano intermediário, em que há um rio a se confundir com uma espécie de estrada, ultrapassados por uma ponte com estrutura de ferro e um fundo em que edifícios, vegetação e estrutura industrial se opõem ao céu azul. Ou seja, uma paisagem ligada às convenções tradicionais, porém concebida dentro do mesmo rigor legeriano que caracterizava suas outras pinturas.

Nota-se também que todas aquelas formas foram recortadas em áreas definidas e sobrepostas para reforçar o caráter bidimensional do suporte, sendo que as únicas exceções residem nas estruturas que sustentam a ponte, na bomba de gasolina e na torre de metal, à esquerda. Apenas essas formas se relacionam com o fundo, pois as demais – a ponte e o vagão entre elas – cortam o campo da pintura, transformando-se em áreas fechadas, sem comunicação.

Esse mesmo isolamento de formas caracteriza as justaposições que Tarsila usou em São Paulo (Gazo). Apenas as árvores e a casa (à esquerda), além da estrutura metálica, (à direita), se relacionam com os planos posteriores, replicando, por assim dizer, as letras garrafais da palavra “GAZO” – estranhamente os únicos elementos em que se percebe um titubear “autoral” na condução do pincel. A fumaça que sai da chaminé, ao fundo à esquerda, parece uma tentativa mal sucedida de buscar equilíbrio entre representação e apresentação.

Existe uma idealização de São Paulo nessas pinturas, uma nostalgia do antigo burgo e que, frente aos novos mobiliários urbanos que invadem a placidez anterior, resiste, mesclando-se a eles por meio de uma ordem que a todo tempo busca escapar à contradição, ao tempo e ao caos. Penso como deve ter sido dificultoso para Tarsila traduzir dos ensinamentos de Léger – focados numa produção pautada no imaginário moderno –, para esse entorno específico da cidade que se transforma de maneira implacável e que a artista parece querer desacelerar, parar, transformando a imagem da quase metrópole numa espécie de aldeia, em cartazes que não celebram a modernidade como mercadoria, uma espécie de ode ao tempo que se esvai e precisa ser detido.

***

Mais uma modernista que “veio depois”, Tarsila, no processo de deglutição da modernidade de Léger, retira dela qualquer resquício de circunstância, de contingência, de história. E nos devolve uma poética ainda colada ao mito ancestral (a ex escravizada, como “a” negra, ou a “caipirinha” e São Paulo como a aldeia), que resiste ao embate com a realidade. Se suas pinturas trazem índices do aqui e do agora – o cartão-postal, a bomba de gasolina etc. – a eles estão fora do agitado do cotidiano, mais em busca da estabilidade mítica do que das incertezas do devir.

[1] – Sobre a permanência de Tarsila do Amaral em Paris, durante 1923, e seu contato com Fernand Léger, consultar: AMARAL, Aracy. Tarsila sua obra e seu tempo. São Paulo: Ed. Perspectiva/Edusp, 1975.

[2] – “Advertising”, Kirk Varnedoe, In VARNEDOE, Kirk/GOPNIK, Adam. High&Low. Modern Art: modern art and popular culture. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1991. Pág. 286.

[3] – Para mais detalhes sobre as ideias de Fernand Lèger a partir da década de 20 ler, entre outros, – LÉGER, Fernand. Funções da pintura. São Paulo: Difusão Europeia do Livro, s.d.

[4] – LÉGER, Fernand. Funções da pintura. São Paulo: Difusão Europeia do Livro, s.d. Pág. 47.

[5] – Um exemplo também significativo da “presença” de Léger na pintura de Tarsila, e do esforço dessa em adaptar as posturas do artista à sua prática de pintora, pode ser percebida em A Feira I, 1924, e A Feira II, 1925. Sabemos o quanto encantava a Léger a disposição das mercadorias nas vitrines dos magazines parisienses. O artista chegou a refletir, inclusive, sobre uma “estética” das vitrines –, para ele, índice fundamental da modernidade urbana. Creio que o interesse de Tarsila em chamar a atenção do observador para a ordenação das mercadorias à venda nas suas duas “Feiras”, pode ser creditado a uma tentativa da pintora em adaptar aquele interesse de Léger à suposta realidade brasileira. É claro que, ao optar pelas barracas de frutas das feiras brasileiras, Tarsila deixou de lado a realidade das vitrines dos centros urbanos do país, reforçando um lado idealizado e “primitivo” do Brasil.

[6] Segundo Aracy Amaral (op.cit. p.95, nota 43), a artista teria produzido duas telas em 1923 com o título Rio de Janeiro. A reprodução aqui exibida, pertencente à Coleção da Fundação Cultural Ema Gordon Klabin, SP, antes teria pertencido à Coleção de Lasar Segall, também em São Paulo.

[7] – Sobre o assunto, consultar sobretudo o capítulo seis do livro (p.75 e segs.).

[8] – Levando-se em conta que ela pode ter ido para a Itália em meados de julho e voltado para São Paulo no início de dezembro, a tempo de passar as festas de final de ano junto à família,

[9] – AMARAL, Aracy. (op.cit.) p.83.

[10] – AMARAL, Aracy. (op.cit.) p. 99.

[11] – Idem.

[12] – Idem, p. 98.

[13] – Baseada em cartas e outros documentos da artista, Aracy Amaral, em seu livro, afirma que Tarsila do Amaral teria assistido a três aulas como aluna no ateliê de Fernand Léger, em 1923. No entanto, em depoimento à revista Veja, (ed.181) de 23 de fevereiro de 1972, a artista afirmou que não chegou a ser aluna do artista francês e sim apenas sua amiga e de sua esposa.

[14] – HEDEL-SAMSON, Brigitte. “Fernand Léger e os amigos brasileiros”.IN BARROS, Regina T. de (coord. Editorial). Fernand Léger. Relações e amizades brasileiras. São Paulo: Pinacoteca de São Paulo, 2009. Pág. 13 e segs.

[15] – Em nota de n. 47, a autora escreve: “Tarsila recorda-se de ter Léger em particular gostado de A Negra, mencionando que gostaria que seus alunos viessem a tela. AMARAL, Aracy. (op.cit.) p.97.