I am out of time! We can’t waste time! Forget these expressions before entering the exhibition Nheë Nheë Nheë: Genealogia do Ócio Tropical, by Márcio Almeida at Sesc Santo Amaro, Recife. Try to plunge into idleness, relax and think that life is an existential adventure.

If you feel like sitting or lying in the exhibition space, after all this can be your moment of discovery, enjoyment, pleasure to meet with yourself. To be in idleness is to be in peace by redesigning life and mediating the place of creative transgression. Experimental loitering is nurtured by doing nothing creative. In short, it is what conveys this subtle show of striking formal cleanliness, and which reflects on labor relations, from the time of colonial Brazil to the present day. The concept has other contours and reaffirms the thought of Antonio Negri, Italian Marxist philosopher when he defines: “Work is capacity for production, social activity, dignity, but on the other hand is slavery, command, alienation”.

The exhibition is aligned with three previous works and the most recent, Nheë Nheë Nheë, is the result of Márcio Almeida’s residence at the Usina de Arte Santa Terezinha, in Zona da Mata, south of Pernambuco. For a few days he experienced moments of action and rest. It produced within free time, which nowadays is in danger of being eliminated by the government. Not working formally is seen by the system as vagrancy, laziness, idleness. Hannah Arendt, in The Human Condition, reminds us that all European words for work also mean pain and effort – in Latin and English labor, in Greek ponos, in French travail, in German Arbeit.

What is distinguished in this work is the way to combine elements that sprout in the exhibition space, since the title of the show born in the origins of our indigenous language. Ñheé, according to anthropologist Adolfo Colombres, means speech. Therefore, Nheë, Nheë, Nheë can be a free translation of chatter. It also refers to a form of control exercised by religious in an attempt to unify tribal languages to facilitate forced catechesis.

In the introductory text, curator Beano de Borba comments on Márcio Almeida’s work as a traditional idleness and savage rite, sustained by an insurgency of free time. The artist’s intention is to “draw a parallel between the issue of western work and tropical idleness”. In this context, it is based on the interference of religions and the strategies of the colonizers in catechizing the indigenous. Leisure and freedom is the binomial that runs through all four installations that make up the show. “In the curation process we started from the new work, Nheë Nheë Nheë, and included other works, developments linked to the Western logic of work and reflecting the distortions practiced by the system.”

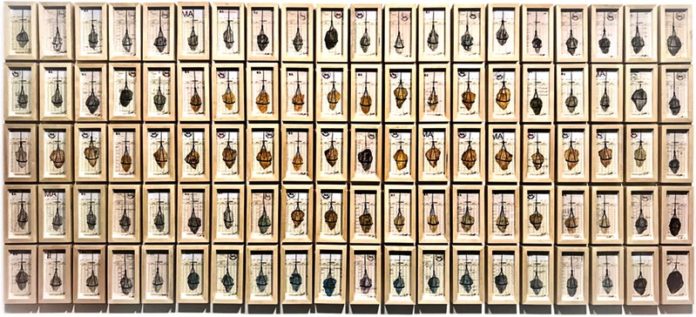

The Nheë Nheë Nheë installation, which is the title of the exhibition, is a delicate exercise made up of thirteen pieces created with olive twigs, shovels and pit iron that shape the work tools. Despite the relatively small space of the gallery, the works flow. The floor-to-ceiling glass wall does not disturb, on the contrary, it incorporates the external landscape, mimicking the vegetation with the dry branches. In another installation, Nosso Descanso é Carregar Pedras, serialism is present in the set of hospital time cards on which the artist illustrates with watercolor images of stones, symbolic elements of slavery since biblical times. The time clock marks the time demanded by the system which, according to Foucault, becomes a form of labor control.

The most comprehensive of these, Waiting for Work is marked by photography, a series of ten images that capture the resting moment of employees after lunch break. The time to do nothing, free reflection and communication between colleagues. This reality of the daily timeline is a lively extension of a field of attraction and repulsion, driven by poetic and social forces. The show closes, Truck Sistem, which touches on one of the cruelest aspects of Brazilian labor, debt bondage. With around 30 carbon papers, collected and graphed, Márcio Almeida puts into question the recurrent debt slavery experienced by the working class of the city and the countryside. This abuse procedure in force in Brazil shows that the worker can not settle his debts with the boss, even those of the canteen, becoming a permanent slave of the employer.

Nowadays, with the man subtracted from the time to which he is entitled, Genealogia do ócio tropical could be a starting point for the package leaflet: Vida outro Modo de Usar? The artist believes so. “I see production as directly linked to free thinking, without compromise, it is precisely in these moments of reflection that we are most productive.” Márcio Almeida constantly proves this remedy. Just start working a work, without any instrument, thinking quietly lying in the hammock, devising ideas, literally in idleness.

Detalhes

André Taniki Yanomami nasceu por volta de 1945 na aldeia Okorasipëki, nas cabeceiras do rio Lobo d’Almada, na Terra Indígena Yanomami, em Roraima. Taniki, além de artista, é xamã, um

Detalhes

André Taniki Yanomami nasceu por volta de 1945 na aldeia Okorasipëki, nas cabeceiras do rio Lobo d’Almada, na Terra Indígena Yanomami, em Roraima. Taniki, além de artista, é xamã, um mediador entre o mundo humano e o mundo espiritual em culturas indígenas e tradicionais, capaz de comunicar-se com espíritos, curar e equilibrar forças visíveis e invisíveis por meio de rituais, cantos e transes. Entre 1976 e 1985, Taniki desenvolveu um conjunto de desenhos em diálogo com uma artista, um antropólogo e missionários. Esta exposição é a primeira dedicada inteiramente à sua obra e reúne 121 desenhos realizados em dois momentos: nas trocas com a fotógrafa suíço-brasileira Claudia Andujar, em 1976–77, e nos encontros com o antropólogo francês Bruce Albert, em 1978, nas aldeias onde o artista-xamã vivia.

Nos desenhos de 1976–77, Taniki criou cenas da visão de mundo yanomami e de rituais funerários que ocorriam na sua comunidade. Esses desenhos, expostos nesta parede, foram realizados em cores já utilizadas pelos Yanomami nas pinturas corporais e cestarias, como preto, roxo e vermelho. No ano seguinte, em diálogo com Albert, Taniki produziu os desenhos expostos na parede oposta a essa, registrando suas visões durante transes xamânicos em composições multicoloridas e vibrantes, com formas abstratas e geométricas. Eles demonstram como Taniki era estimulado espiritual e visualmente pelo poder da yãkoana, pó psicoativo proveniente da casca de uma árvore amazônica. Similar à ayahuasca, é inalado pelos xamãs e alimenta os espíritos.

Na visão de mundo yanomami, a noção de imagem (utupë) não é apenas a compreensão visível, mas também a essência interior que constitui o núcleo vital de todas as coisas. O título da exposição, Ser imagem (Në utupë, em yanomami), refere-se ao movimento espiritual que Taniki faz, nos rituais xamânicos, de deixar de ser apenas humano e conseguir existir em forma de imagem, assim como os espíritos. Até hoje, Taniki exerce em sua comunidade suas responsabilidades xamânicas, mediando relações entre os espíritos ancestrais e os Yanomami não xamãs. Do mesmo modo, embora não desenhe mais, suas obras continuam a atestar seu poder intermediador, tornando o invisível (as imagens-espíritos) visível (as imagens-desenhos).

Curadoria: Adriano Pedrosa, diretor artístico, e Mateus Nunes, curador assistente, MASP

Serviço

Exposição | André Taniki Yanomami: ser imagem

De 05 de dezembro a 05 de abril

Terças grátis, das 10h às 20h (entrada até as 19h); quarta e quinta das 10h às 18h (entrada até as 17h); sexta das 10h às 21h (entrada gratuita das 18h às 20h30); sábado e domingo, das 10h às 18h (entrada até as 17h); fechado às segundas.

Agendamento on-line obrigatório pelo link masp.org.br/ingressos

Período

Local

MASP

Avenida Paulista, 1578, São Paulo

Detalhes

A Olho Nu, maior retrospectiva realizada pelo prestigiado artista brasileiro Vik Muniz chega ao Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Bahia (MAC_Bahia). Com mais de 200 obras distribuídas em 37 séries, A

Detalhes

A Olho Nu, maior retrospectiva realizada pelo prestigiado artista brasileiro Vik Muniz chega ao Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Bahia (MAC_Bahia).

Com mais de 200 obras distribuídas em 37 séries, A Olho Nu reúne trabalhos fundamentais de diferentes fases da trajetória de Vik Muniz, reconhecido internacionalmente por sua capacidade de transformar materiais cotidianos em imagens de forte impacto visual e simbólico. Chocolate, açúcar, poeira, lixo, fragmentos de revista e arame são alguns dos elementos que integram seu vocabulário artístico e aproximam sua produção tanto da arte pop quanto da vida cotidiana. O público poderá acompanhar desde seus primeiros experimentos escultóricos até obras que marcam a consolidação da fotografia como eixo central de sua criação.

Entre os destaques, a exposição traz quatro peças inéditas ao MAC_Bahia, que não integraram a etapa de Recife: Queijo (Cheese), Patins (Skates), Ninho de Ouro (Golden Nest) e Suvenir nº 18. A mostra apresenta também obras nunca exibidas no Brasil, como Oklahoma, Menino 2 e Neurônios 2, vistas anteriormente apenas nos Estados Unidos.

A retrospectiva ocupa o MAC_Bahia e se expande para outros dois espaços da cidade: o ateliê do artista, no Santo Antônio Além do Carmo, que receberá encontros e visitas especiais, e a Galeria Lugar Comum, na Feira de São Joaquim, onde será exibida uma instalação inédita inspirada na obra Nail Fetish. Esta é a primeira vez que Vik Muniz apresenta um trabalho no local, reforçando o diálogo entre sua produção e territórios populares de Salvador.

Exposição A Olho Nu, de Vik Muniz, no Museu de Arte Contemporânea. Foto: Vik Muniz

Apontada como fundamental para compreender a transição do artista do objeto para a fotografia, a série Relicário (1989–2025) recebe o visitante logo na entrada do MAC_Bahia. Não exibida desde 2014, ela apresenta esculturas tridimensionais que ajudam a entender a virada conceitual de Muniz, quando o artista percebeu que podia construir cenas pensadas exclusivamente para serem fotografadas, movimento que redefiniu sua carreira internacional.

Para o curador Daniel Rangel, também diretor do MAC_Bahia, a chegada de A Olho Nu tem significado especial. “Essa é a primeira grande retrospectiva dedicada ao trabalho de Vik Muniz, com um recorte pensado para criar um diálogo entre suas obras e a cultura da região”, afirma.

A chegada da retrospectiva a Salvador também fortalece a parceria entre o IPAC e o Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil (CCBB), responsável pela realização da mostra e em processo avançado de implantação de sua unidade no Palácio da Aclamação, prédio histórico sob gestão do Instituto. Antes mesmo de abrir suas portas oficialmente na Bahia, o CCBB Salvador já vem promovendo ações culturais na capital, entre elas a apresentação da maior exposição dedicada ao artista.

Para receber A Olho nu, o IPAC e o MAC_Bahia mobilizam uma estrutura completa que inclui serviços de manutenção, segurança, limpeza, iluminação museológica e logística operacional, além da atuação da equipe de mediação e das ações educativas voltadas para escolas, universidades, grupos culturais e visitantes em geral. A expectativa é de que o museu receba cerca de 400 pessoas por dia durante o período da mostra, consolidando o MAC_Bahia como um dos principais equipamentos de circulação de arte contemporânea no Nordeste. Não por acaso, o Museu está indicado entre as melhores instituições de 2025 pela Revista Continente.

Com acesso gratuito e programação educativa contínua, A Olho Nu deve movimentar intensamente a agenda cultural de Salvador nos próximos meses. A exposição oferece ao público a oportunidade de mergulhar na obra de um dos artistas brasileiros mais celebrados da atualidade e de experimentar diferentes etapas de seu processo criativo, reafirmando o MAC_Bahia como referência na promoção de grandes mostras nacionais e internacionais.

Serviço

Exposição | A Olho Nu

De 13 de dezembro a 29 de março

Terça a domingo, das 10h às 20h

Período

Local

MAC Bahia

Rua da Graça, 284, Graça – Salvador, BA

Detalhes

A Nara Roesler São Paulo tem o prazer de apresentar Telúricos, exposição coletiva com curadoria de Ana Carolina Ralston que reúne 16 artistas para investigar a força profunda da matéria terrestre

Detalhes

A Nara Roesler São Paulo tem o prazer de apresentar Telúricos, exposição coletiva com curadoria de Ana Carolina Ralston que reúne 16 artistas para investigar a força profunda da matéria terrestre e as relações viscerais entre o corpo humano e o corpo da Terra. A mostra fundamenta-se no conceito de imaginação telúrica, inspirado pelo filósofo Gaston Bachelard, para explorar como a arte pode escavar superfícies e tocar o que há de mais denso e vibrante na natureza e na tecnologia. A exposição propõe um deslocamento do olhar ocular-centrista, convidando o público a uma experiência multissensorial que atravessa o olfato, a audição e a tactilidade. Como afirma a curadora, “a imaginação telúrica cava sempre em profundidade, não se contentando com superfícies”. Em Telúricos, a Terra deixa de ser um cenário passivo para tornar-se protagonista e ator político, transformando nossos modos de habitar.

A seleção curatorial estabelece um diálogo entre nomes históricos da Land Art e vozes contemporâneas, onde a matéria deixa de ser suporte para se tornar corpo e voz. Richard Long representa a tradição da intervenção direta no território, enquanto artistas como Brígida Baltar apresentam obras emblemáticas, como Enterrar é plantar, que reforçam o ciclo de vida e renascimento da matéria. A mostra conta ainda com a presença de Isaac Julien, Not Vital e uma obra em ametista de Amelia Toledo, escolhida por sua ressonância mineral e espiritual. A instalação de C. L. Salvaro simula o interior da Terra através de uma passagem experimental de tela e plantio, evocando arqueologia e memória, enquanto a artista Amorí traz pinturas e esculturas que narram a metamorfose de seu corpo e sua história. A dimensão espiritual e a transitoriedade indígena são exploradas por Kuenan Mayu, que utiliza pigmentos naturais, enquanto Alessandro Fracta, aciona mundos ancestrais e ritualísticos ao realizar trabalhos com bordados em fibra de juta.

A experiência sensorial é um dos pilares da mostra, conduzida especialmente pelo trabalho de Karola Braga, cujas esculturas em cera de abelha exalam os aromas da natureza. Na vitrine da galeria, a estrutura dourada Perfumare, libera fumaça, mimetizando os vapores exalados pelos vulcões, expressão radical da capacidade do planeta de alterar-se, de reinventar sua forma e de impor ritmos. A cosmologia e a sonoridade também se fazem presentes com os neons de Felippe Moraes, que desenham constelações de signos terrestres como Touro, Virgem e Capricórnio, e a dimensão sonora de Denise Alves-Rodrigues. O percurso completa-se com os móbiles da série “Organoide” de Lia Chaia, as paisagens imaginativas de Ana Sant’anna, a materialidade de Flávia Ventura e as investigações sobre a natureza de Felipe Góes. Cada obra funciona como um documento de negociação com o planeta, onde o chão que pisamos também protesta e fala.

Serviço

Exposição | Dada Brasilis

De 05 de fevereiro a 12 de março

Segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h, sábado, das 11h às 15h

Período

Local

Galeria Nara Roesler - SP

Avenida Europa, 655, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

Com curadoria de Osmar Paulino, Marlon Amaro expõe Mirongar, mostra reúne obras centrais de sua trajetória, reconhecido por abordar de forma contundente temas como o racismo estrutural, o apagamento da

Detalhes

Com curadoria de Osmar Paulino, Marlon Amaro expõe Mirongar, mostra reúne obras centrais de sua trajetória, reconhecido por abordar de forma contundente temas como o racismo estrutural, o apagamento da população negra e as dinâmicas históricas de violência e subserviência impostas a corpos negros.

Serviço

Exposição | Mirongar

De 13 de janeiro a 21 de março

Quarta a Domingo, das 14h às 21h

Período

Local

Casa do Benin

Rua Padre Agostinho Gomes, 17 - Pelourinho, Salvador - BA

Detalhes

Em sua prática, a artista franco-brasileira Julia Kater investiga a relação entre a paisagem, a cor e a superfície. Ela transita pela fotografia e pela colagem, concentrando-se na construção da

Detalhes

Em sua prática, a artista franco-brasileira Julia Kater investiga a relação entre a paisagem, a cor e a superfície. Ela transita pela fotografia e pela colagem, concentrando-se na construção da imagem por meio do recorte e da justaposição. Na fotografia, Kater parte do entendimento de que toda imagem é, por definição, um fragmento – um enquadramento que recorta e isola uma parte da cena. Em sua obra, a imagem não é apenas um registro de um instante, mas sim, resultado de um deslocamento – algo que se desfaz e se recompõe do mesmo gesto. As imagens, muitas vezes próximas, não buscam documentar, mas construir um novo campo de sentido. Nas colagens, o gesto do recorte ganha corpo. Fragmentos de fotografias são manualmente cortados, sobrepostos e organizados em camadas que criam passagens visuais marcadas por transições sutis de cor. Esses acúmulos evocam variações de luz, atmosferas e a própria passagem do tempo através de gradações cromáticas.

Na individual Duplo, Julia Kater apresenta trabalhos recentes, desenvolvidos a partir da pesquisa realizada durante sua residência artística em Paris. “Minha pesquisa se concentra na paisagem e na forma como a cor participa da construção da imagem – ora como elemento acrescentado à fotografia, ora como algo que emerge da própria superfície. Nas colagens, a paisagem é construída por recortes, justaposições e gradações de cor. Já nos trabalhos em tecido, a cor atua a partir da própria superfície, por meio do tingimento manual, atravessando a fotografia impressa. Esses procedimentos aprofundam a minha investigação sobre a relação entre a paisagem, a cor e a superfície”, explica a artista.

Em destaque, duas obras que serão exibidas na mostra: uma em tecido que faz parte da nova série e um díptico inédito. Corpo de Pedra (Centauro), 2025, impressão digital pigmentária sobre seda tingida à mão com tintas a base de plantas e, Sem Título, 2025, colagem com impressão em pigmento mineral sobre papel matt Hahnemüle 210g, díptico com dimensão de 167 x 144 cm cada.

A artista comenta: “dou continuidade às colagens feitas a partir do recorte de fotografia impressa em papel algodão e passo a trabalhar com a seda também como suporte. O processo envolve o tingimento manual do tecido com plantas naturais, como o índigo, seguido da impressão da imagem fotográfica. Esse procedimento me interessa por sua proximidade com o processo fotográfico analógico, sobretudo a noção de banho, de tempo de imersão e de fixação da cor na superfície”. Todas as obras foram produzidas especialmente para a exposição, que fica em cartaz até 07 de março de 2026.

Serviço

Exposição | Julia Kater: Duplo

De 22 de janeiro a 07 de março

Segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h; sábado, das 10h às 15h

Período

Local

Simões de Assis

Al. Lorena, 2050 A, Jardins - São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A Galatea tem o prazer de apresentar Guilherme Gallé: entre a pintura e a pintura, primeira individual do artista paulistano Guilherme Gallé (1994, São Paulo), na unidade da galeria na

Detalhes

A Galatea tem o prazer de apresentar Guilherme Gallé: entre a pintura e a pintura, primeira individual do artista paulistano Guilherme Gallé (1994, São Paulo), na unidade da galeria na rua Padre João Manuel. A mostra reúne mais de 20 pinturas inéditas, realizadas em 2025, e conta com texto crítico do curador e crítico de arte Tadeu Chiarelli e com texto de apresentação do crítico de arte Rodrigo Naves.

A exposição apresenta um conjunto no qual Gallé revela um processo contínuo de depuração: um quadro aciona o seguinte, num movimento em que cor, forma e espaço se reorganizam respondendo uns aos outros. Situadas no limiar entre abstração e sugestão figurativa, suas composições, sempre sem título, convidam à lenta contemplação, dando espaço para que o olhar oscile entre a atenção ao detalhe e ao conjunto.

Partindo sempre de um “lugar” ou pretexto de realidade, como paisagens ou naturezas-mortas, mas sem recorrer ao ponto de fuga renascentista, Gallé mantém a superfície pictórica deliberadamente plana. As cores tonais, construídas em camadas, estruturam o plano com uma matéria espessa, marcado por incisões, apagamentos e pentimentos, que dão indícios do processo da pintura ao mesmo tempo que o impulsionam.

Entre as exposições das quais Guilherme participou ao longo de sua trajetória, destacam-se: Joaquín Torres García – 150 anos, (Coletiva, Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil – CCBB, São Paulo / Brasília / Belo Horizonte, 2025–2026); Ponto de mutação (Coletiva, Almeida & Dale, São Paulo, 2025); O silêncio da tradição: pinturas contemporâneas (Coletiva, Centro Cultural Maria Antonia, São Paulo, 2025); Para falar de amor (Coletiva, Noviciado Nossa Senhora das Graças Irmãs Salesianas, São Paulo, 2024); 18º Território da Arte de Araraquara (2021); Arte invisível (Coletiva, Oficina Cultural Oswald de Andrade, São Paulo, 2019); e Luiz Sacilotto, o gesto da razão (Coletiva, Centro Cultural do Alumínio, São Paulo, 2018).

Serviço

Exposição | Guilherme Gallé: entre a pintura e a pintura

De 22 de janeiro a 07 de março

Segunda a quinta, das 10 às 19h, sexta, das 10 às 18h, Sábado, das 11h às 17h

Período

Local

Galatea Padre João Manuel

R. Padre João Manuel, 808, Jardins – São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

O Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (MAM Rio) recebe, em janeiro de 2026, a primeira edição brasileira de Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile (Vela/Tela – Tela/Vela), projeto seminal do

Detalhes

O Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (MAM Rio) recebe, em janeiro de 2026, a primeira edição brasileira de Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile (Vela/Tela – Tela/Vela), projeto seminal do artista Daniel Buren (1938, Boulogne-Billancourt), realizado em parceria com a Galeria Nara Roesler. Iniciado em 1975, o trabalho transforma velas de barcos em suportes de arte, deslocando o olhar do espectador e ativando o espaço ao redor por meio do movimento, da cor e da forma. Ao longo de cinco décadas, o projeto foi apresentado em cidades como Genebra, Lucerna, Miami e Minneapolis, sempre em diálogo direto com a paisagem e o contexto locais.

Concebida originalmente em Berlim, em 1975, Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile destaca o uso das listras verticais que Daniel Buren define como sua “ferramenta visual”. O próprio título da obra explicita o deslocamento proposto pelo artista ao articular dois campos centrais do modernismo do século 20 — a pintura abstrata e o readymade —, transformando velas de barcos em pinturas e ampliando o campo de ação da obra para além do espaço expositivo.

“Trata-se de um trabalho feito ao ar livre e que conta com fatores externos e imprevisíveis, como clima, vento, visibilidade e posicionamento das velas e barcos, de modo que, ainda que tenha sido uma ação realizada dezenas de vezes, ela nunca é idêntica, tal qual uma peça de teatro ou um ato dramático”, disse Daniel Buren, em conversa com Pavel Pyś, curador do Walker Art Center de Minneapolis, publicada pelo museu em 2018.

No dia 24 de janeiro, a ação tem início com uma regata-performance na Baía de Guanabara. Onze veleiros da classe Optimist partem da Marina da Glória e percorrem o trajeto até a Praia do Flamengo, equipados com velas que incorporam as listras verticais brancas e coloridas criadas por Buren. Em movimento, as velas se convertem em intervenções artísticas vivas, ativando o espaço marítimo e o cenário do Rio como parte constitutiva da obra. O público poderá acompanhar a ação desde a orla, e toda a performance será registrada.

Após a conclusão da regata, as velas serão deslocadas para o foyer do MAM Rio, onde passarão a integrar a exposição derivada da regata, em cartaz de 28 de janeiro a 12 de abril de 2026. Instaladas em estruturas autoportantes, as onze velas – com 2,68 m de altura (2,98 m com a base) – serão dispostas no espaço de acordo com a ordem de chegada da regata, seguindo o protocolo estabelecido por Buren desde as primeiras edições do projeto. O procedimento preserva o vínculo direto entre a performance e a exposição, e evidencia a transformação das velas de objetos utilitários em objetos artísticos. A expografia é assinada pela arquiteta Sol Camacho.

“Desde os anos 1960, Buren desenvolve uma reflexão crítica sobre o espaço e as instituições, sendo um dos pioneiros da arte in situ e da arte conceitual. Embora Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile tenha circulado por diversos países ao longo dos últimos 50 anos, esta é a primeira vez que a obra é apresentada no Brasil. A proximidade do MAM Rio com a Baía de Guanabara, sua história na experimentação e sua arquitetura integrada ao entorno fazem do museu um espaço particularmente privilegiado para a obra do artista”, comenta Yole Mendonça, diretora executiva do MAM Rio.

Ao prolongar no museu uma experiência iniciada no mar, Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile estabelece uma continuidade entre a ação na Baía de Guanabara e sua apresentação no espaço expositivo do MAM Rio, integrando paisagem, arquitetura e percurso em uma mesma experiência artística.

“A maneira como Buren tensiona a relação da arte com espaços específicos, principalmente com os espaços públicos, é fundamental para entender a história da arte contemporânea. E essa peça Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile, que começa na Baía de Guanabara e que chega aos espaços internos do museu, é um exemplo perfeito dessa prática”, comenta Pablo Lafuente, diretor artístico do MAM Rio.

Em continuidade ao projeto, a Nara Roesler Books publicará uma edição dedicada à presença de Daniel Buren no Brasil, reunindo ensaios críticos e documentos da realização de Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile no Rio de Janeiro, em 2026.

Serviço

Exposição | Voile/Toile – Toile/Voile (Vela/Tela – Tela/Vela)

De 28 de janeiro a 12 de abril

Quartas, quintas, sextas, sábados domingos e feriados, das 10h às 18h

Período

Detalhes

Galatea e Nara Roesler têm a alegria de colaborar pela primeira vez na realização da mostra Barracas e fachadas do nordeste, Com curadoria de Tomás Toledo, sócio-fundador da Galatea e Alana

Detalhes

Galatea e Nara Roesler têm a alegria de colaborar pela primeira vez na realização da mostra Barracas e fachadas do nordeste,

Com curadoria de Tomás Toledo, sócio-fundador da Galatea e Alana Silveira, diretora da Galatea Salvador, a coletiva propõe uma interlocução entre os programas das galerias ao explorar as afinidades entre os artistas Montez Magno (1934, Pernambuco), Mari Ra (1996, São Paulo), Zé di Cabeça (1974, Bahia), Fabio Miguez (1962, São Paulo) e Adenor Gondim (1950, Bahia). A mostra propõe um olhar ampliado para as arquiteturas vernaculares que marcam o Nordeste: fachadas urbanas, platibandas ornamentais, barracas de feiras e festas e estruturas efêmeras que configuram a paisagem social e cultural da região.

Nesse conjunto, Fabio Miguez investiga as fachadas de Salvador como um mosaico de variações arquitetônicas enquanto Zé di Cabeça transforma registros das platibandas do subúrbio ferroviário soteropolitano em pinturas. Mari Ra reconhece afinidades entre as geometrias que encontrou em Recife e Olinda e aquelas presentes na Zona Leste paulistana, revelando vínculos construídos pela migração nordestina. Já Montez Magno e Adenor Gondim convergem ao destacar as formas vernaculares do Nordeste, Magno pela via da abstração geométrica presentes nas séries Barracas do Nordeste (1972-1993) e Fachadas do Nordeste (1996-1997) e Gondim pelo registro fotográfico das barracas que marcaram as festas populares de Salvador.

A parceria entre as galerias se dá no aniversário de 2 anos da Galatea em Salvador e reforça o seu intuito de fazer da sede na capital baiana um ponto de convergência para intercâmbios e trocas entre artistas, agentes culturais, colecionadores, galerias e o público em geral.

Serviço

Exposição | Barracas e fachadas do nordeste

De 30 de janeiro a 30 de maio

Terça – quinta, das 10 às 19h, sexta, das 10 às 18h, sábado, das 11h às 15h

Período

Local

Galeria Galatea Salvador

R. Chile, 22 - Centro, Salvador - BA

Detalhes

A Pinacoteca de São Bernardo do Campo apresenta, entre os dias 31 de janeiro e 28 de março de 2026, uma exposição individual do artista Daniel Melim (São Bernardo do Campo, SP – 1979). Com curadoria assinada pelo

Detalhes

A Pinacoteca de São Bernardo do Campo apresenta, entre os dias 31 de janeiro e 28 de março de 2026, uma exposição individual do artista Daniel Melim (São Bernardo do Campo, SP – 1979). Com curadoria assinada pelo pesquisador e especialista em arte pública Baixo Ribeiro e produção da Paradoxa Cultural, a mostra Reflexos Urbanos: a arte de Daniel Melim reúne um conjunto de 12 obras – dentre elas oito trabalhos inéditos.

A exposição apresenta uma verdadeira introspectiva do trabalho de Daniel Melim – um mergulho em seu processo criativo a partir do olhar de dentro do ateliê. Ao lado de obras que marcaram sua trajetória, o público encontrará trabalhos inéditos que apontam novos caminhos em sua produção. Entre os destaques, uma pintura em grande formato — 2,5m x 12m — e um mural coletivo que será produzido ao longo da mostra.

Com obras em diferentes formatos e dimensões – pinturas em telas, relevos, instalação, cadernos, elementos do ateliê do artista -, a mostra aborda o papel da arte urbana na construção de identidades coletivas, a ocupação simbólica dos espaços públicos e o desafio de trazer essas linguagens para o contexto institucional, sem perder seu caráter de diálogo com a comunidade.

O recorte proposto pela curadoria de Baixo Ribeiro conecta passado e presente, mas principalmente, evidencia como Melim transforma referências visuais do cotidiano em obras que geram reflexão crítica, possibilitando criar pontes entre o espaço público e o institucional.

A expografia de “Reflexos Urbanos: a arte de Daniel Melim” foi pensada como um ateliê expandido, com o intuito de aproximar o público do processo criativo de Melim. Dentro do espaço expositivo, haverá um mural colaborativo, no qual os visitantes poderão experimentar técnicas como stencil e lambe-lambe. Essa iniciativa integra a proposta educativa da mostra e transforma o visitante em coautor, fortalecendo a relação entre público e obra.

“Sempre me interessei pela relação entre a arte e o espaço urbano. O stencil foi minha primeira linguagem e continua sendo o ponto de partida para criar narrativas visuais que dialogam com a vida cotidiana. Essa mostra é sobre esse diálogo: cidade, obra e público”, explica Daniel Melim.

Artista visual e educador, reconhecido como um dos principais nomes da arte urbana brasileira, Daniel Melim iniciou sua trajetória artística no final dos anos 1990 com grafite e stencil nas ruas do ABC Paulista. Desenvolve uma pesquisa autoral sobre o stencil como meio expressivo, resgatando sua importância histórica na formação da street art no Brasil e expandindo seus potenciais pictóricos para além do espaço público. Sua produção se caracteriza pelo diálogo entre obra, arquitetura e cidade, frequentemente instalada em áreas em processo de transformação urbana.

“Essa exposição individual é uma forma de me reconectar com o lugar onde tudo começou. São Bernardo do Campo foi minha primeira escola de arte – não apenas pela faculdade, mas pela rua, pelos muros, pelas greves que eu vi quando ainda era criança. Essa experiência formou a minha visão de mundo. Trazer esse trabalho de volta, no espaço da Pinacoteca, é como abrir o meu ateliê para a cidade que tanto me acolheu e me fez crescer”, comenta.

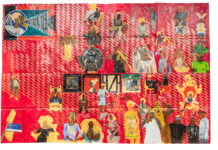

Os stencils, o imaginário gráfico da publicidade, críticas à sociedade de consumo e ao cotidiano urbano são marcas do trabalho de Melim. Cores chapadas, sobreposições e composições equilibradas são algumas das características que aparecem tanto nas obras históricas de Daniel Melim, quanto em novos trabalhos que o artista está produzindo para a individual. “Reflexos Urbanos: a arte de Daniel Melim” é um convite para o visitante mergulhar e se aproximar do processo criativo do artista. A mostra fica em cartaz até o dia 28 de março de 2026.

A exposição “Reflexos Urbanos: a arte de Daniel Melim” é realizada com apoio da Política Nacional Aldir Blanc de Fomento à Cultura (PNAB); do Programa de Ação Cultural – ProAC, da Secretaria da Cultura, Economia e Indústria Criativas do Governo do Estado de São Paulo; do Ministério da Cultura e do Governo Federal.

Serviço

Exposição | Reflexos Urbanos: a arte de Daniel Melim

De 31 de janeiro e 28 de março

Terça, das 9h às 20h; quarta a sexta, das 9h às 17h; sábado, das 10h às 16h

Período

Local

Pinacoteca de São Bernardo do Campo

Rua Kara, nº 105 - Jardim do Mar - São Bernardo do Campo - SP

Detalhes

A Luciana Brito Galeria abre sua programação de 2026 com a exposição Ainda Bem, Atravessei as Nuvens, a segunda da artista Gabriela Machado na galeria. A mostra destaca pinturas inéditas

Detalhes

A Luciana Brito Galeria abre sua programação de 2026 com a exposição Ainda Bem, Atravessei as Nuvens, a segunda da artista Gabriela Machado na galeria. A mostra destaca pinturas inéditas de maior dimensão – em diálogo com outras menores – realizadas entre 2024 e 2026, ocupando todo o espaço do Pavilhão. O texto crítico é assinado por Amanda Abi Khalil.

As crônicas do cotidiano, os cenários reais e oníricos, a temperatura e o brilho das cores, as sensações do dia a dia. Nada escapa ao crivo de um imaginário sensível que orienta o olhar de Gabriela Machado. A artista seleciona aquilo que lhe é mais atraente e o traduz para a linguagem pictórica. Neste conjunto de pinturas inéditas, produzidas nos últimos anos, ela articula fragmentos de histórias e memórias, além de cenas de paisagens captadas em viagens. Esses pequenos acontecimentos, cenas ou observações da vida, embora banais à primeira vista, ganham sentido, densidade e poesia quando reinterpretados pela artista.

Diferentemente de sua primeira exposição na galeria, realizada em 2024, as pinturas de Ainda Bem, Atravessei as Nuvens apresentam-se agora mais figurativas, revelando um jogo híbrido que articula não apenas a percepção imediata daquilo que o olhar alcança, mas também o imaginário e a memória da artista. O universo fantástico circense, por exemplo, surge em diversas obras, como Marambaia (2026) e Ainda Bem, Atravessei as Nuvens (2026), nas quais a figura do leão é retratada a partir de um repertório infantil compartilhado por sua geração.

Em outras pinturas de menor formato, aparecem paisagens que conjugam céu, vegetação e mar, assim como retratos de objetos e esculturas. Em todas elas, contudo, a artista enfatiza a luminosidade e o brilho, elementos que se impõem de imediato ao olhar do espectador e traduzem uma atmosfera de leveza e mistério deliberadamente construída. Já nas obras Largo do Machado (2026), Luzinhas (2014–2025) e Veronese (2013–2025), as luzes de Natal assumem o papel de protagonistas. Segundo explica a artista, o efeito luminoso é produzido deliberadamente durante o processo de produção: em uma primeira etapa ela trabalha com a tinta acrílica, para então finalizar com a tinta a óleo.

O fundo rosa observado em algumas pinturas, como em Ginger (2026), foi inspirado na tonalidade dos tapumes dos canteiros de obra. Outro detalhe também relevante é a moldura reproduzida pela artista em alguns trabalhos de menor formato, funcionando como uma extensão da pintura e contribuindo para a construção de uma maior profundidade espacial.

Serviço

Exposição | Ainda Bem, Atravessei as Nuvens

De 05 de fevereiro a 21 de março

Segunda, das 10h às 18h, terça a sexta, das 10h às 19h, sábado, das 11h às 17h

Período

Detalhes

A Gomide&Co tem o prazer de apresentar ANTONIO DIAS / IMAGE + MIRAGE, primeira individual de Antonio Dias (1944–2018) na galeria. Organizada em parceria com a Sprovieri, Londres, a partir de obras do artista preservadas

Detalhes

A Gomide&Co tem o prazer de apresentar ANTONIO DIAS / IMAGE + MIRAGE, primeira individual de Antonio Dias (1944–2018) na galeria. Organizada em parceria com a Sprovieri, Londres, a partir de obras do artista preservadas por Gió Marconi, a exposição tem organização e texto crítico de Gustavo Motta e expografia de Deyson Gilbert.

A abertura acontece no dia 10 de fevereiro (terça-feira), às 18h, e a exposição segue em cartaz até 21 de março. Entre as obras em exibição, a exposição destaca sete pinturas pertencentes à Gió Marconi realizadas por Antonio Dias entre 1968 e 71, em seus anos iniciais em Milão, demarcando um momento importante na trajetória do artista.

No dia 14 de março (sábado), às 11h, haverá o lançamento de uma publicação que acompanha a mostra. Também com organização e texto de Gustavo Motta, a publicação apresenta o conjunto completo de obras do artista sob a guarda de Gió Marconi, além de documentação complementar sobre seu período de execução. Na ocasião do lançamento, haverá uma mesa redonda com a presença de Gustavo Motta, Sergio Martins e Lara Cristina Casares Rivetti. A mediação será de Deyson Gilbert.

Nascido em Campina Grande (PB) em 1944, Antonio Dias mudou-se com a família para o Rio de Janeiro em 1957, onde iniciou sua carreira artística destacando-se com uma produção que logo foi associada à Pop Arte e à Nova Figuração. Em meados da década de 1960, o artista deixou o Brasil – em um contexto marcado pela Ditadura Militar – e seguiu para Paris, após receber uma bolsa do governo francês por sua participação na 4ª Bienal de Paris. Na Europa, o trabalho de Dias passou a apresentar uma configuração mais conceitual, chamando a atenção do galerista Giorgio Marconi (1930–2024), fundador do Studio Marconi (1965–1992) – espaço que desde seu início foi referência para a arte contemporânea de Milão.

Sob a representação da galeria, Dias decidiu fixar-se na cidade, onde manteve uma de suas residências até o final de sua vida. Lá, estabeleceu estreitas relações com artistas como Mario Schifano, Luciano Fabro, Alighiero Boetti e Giulio Paolini. As obras desse período, apresentadas na exposição, refletem a consolidação da linguagem conceitual do artista em seus primeiros anos na Europa, marcada pela precisão formal, com superfícies austeras combinadas a palavras, frases ou diagramas que operam como comentários autorreflexivos sobre o fazer artístico como atividade mental. O período antecipa – e em parte coincide – com a produção da série The Illustration of Art (1971–78), considerada uma das mais emblemáticas do artista.

As obras realizadas por Dias em Milão sintetizam uma virada decisiva na trajetória do artista, na qual a pintura se torna simultaneamente mais sóbria e mais reflexiva. Por meio de grandes campos monocromáticos, palavras isoladas e estruturas rigorosamente diagramadas, o artista reduz a imagem ao essencial e transforma o quadro em um espaço de pensamento. Conforme Motta esclarece, o que se vê é menos importante do que o que falta: a pintura passa a operar como um dispositivo aberto, que convoca o espectador a completar sentidos e a produzir imagens mentais. Ao incorporar procedimentos gráficos oriundos do design e da comunicação de massa, Dias desloca a pintura do terreno da representação para o da problematização, articulando, nas palavras do artista, uma “arte negativa” que reflete sobre o próprio estatuto da imagem e sobre o fazer artístico como atividade intelectual. Nesse conjunto, consolida-se uma linguagem em que a obra não oferece respostas, mas se apresenta como campo de tensão entre palavra, superfície e imaginação.

A mostra em São Paulo dá sequência à exposição apresentada pela Sprovieri, em Londres, em outubro de 2025, composta por obras do mesmo período – todas pertencentes à Gió Marconi, filho de Giorgio. À frente da Galleria Gió Marconi desde 1990, após ter trabalhado com o pai no espaço experimental para jovens artistas chamado Studio Marconi 17 (1987–1990), Gió também é responsável pela Fondazioni Marconi, fundada em 2004 com o propósito de dar sequência ao legado do antigo Studio Marconi.

Entre as obras apresentadas na exposição da Gomide&Co, figuram pinturas que estiveram presentes na individual inaugural de Antonio Dias no Studio Marconi, em 1969, que contou com texto crítico de Tommaso Trini, além da mais recente dedicada ao artista pela fundação, Antonio Dias – Una collezione, 1968–1976 (2017). A seleção também compreende obras que estiveram em outras ocasiões importantes da carreira do artista, como a histórica (e polêmica) Guggenheim International Exhibition de 1971 e a 34ª Bienal de São Paulo (2021).

A exposição na Gomide&Co também se destaca por oferecer um olhar mais contemporâneo para os primeiros anos de Dias em Milão. A galeria reuniu uma equipe jovem de renome no sentido de atualizar as perspectivas sobre a produção do artista no período. A começar pela organização, sob responsabilidade de Gustavo Motta, considerado atualmente um dos intelectuais da nova geração mais reconhecidos quando se trata de Antonio Dias, tendo assinado a curadoria de Antonio Dias / Arquivo / O Lugar do Trabalho no Instituto de Arte Contemporânea (IAC) em 2021, exposição baseada no acervo documental do artista pertencente à instituição. O projeto expográfico é do artista Deyson Gilbert, que foi responsável pela expografia da mostra curada por Motta no IAC. No caso da exposição na galeria, a proposta de Gilbert anseia refletir e dar continuidade ao processo estético próprio da produção de Dias no período.

Além das obras, a exposição apresenta também uma seleção inédita de documentos do Fundo Antonio Dias do acervo do IAC, com materiais que ainda não estavam disponíveis na instituição na época da exposição de 2021. Complementa a equipe o estúdio M-CAU, da artista Maria Cau Levy, responsável pelo projeto gráfico da publicação.

Reunindo obras históricas, documentação inédita e uma equipe que dialoga diretamente com o legado crítico de Antonio Dias, a exposição reafirma a atualidade e a complexidade da produção do artista no contexto internacional. ANTONIO DIAS / IMAGE + MIRAGE propõe não apenas uma revisão de um momento decisivo da trajetória de Dias, mas também uma leitura renovada de sua contribuição para a arte conceitual, evidenciando como as questões formuladas pelo artista no final dos anos 1960 seguem ressoando de maneira incisiva no debate contemporâneo.

Serviço

Exposição | ANTONIO DIAS / IMAGE + MIRAGE

De 10 de fevereiro a 21 de março

Segunda a sexta, das 10h às 19h; sábados, das 11h às 17h

Período

Local

Gomide & Co

Avenida Paulista, 2644 01310-300 - São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

Prestes a completar 95 anos, Augusto de Campos publicou recentemente o livro “pós poemas” (2025), que reúne um conjunto de trabalhos, compreendido como um marco de síntese da evolução de

Detalhes

Prestes a completar 95 anos, Augusto de Campos publicou recentemente o livro “pós poemas” (2025), que reúne um conjunto de trabalhos, compreendido como um marco de síntese da evolução de sua pesquisa poética. Produzidas ao longo das últimas duas décadas, as obras reunidas no volume deram origem a uma seleção transposta para o espaço da Sala Modernista da galeria, propondo uma experiência não apenas visual, mas também espacial, em diálogo com o ambiente projetado por Rino Levi. No contexto da exposição, os poemas deixam de ser apenas objetos de leitura para se afirmarem como experiências visuais e espaciais: letras tornam-se imagens, cores assumem função semântica, e a disposição gráfica instaura ritmos e tensões que solicitam uma percepção ativa do público.

O poema de Augusto de Campos não se organiza pela linearidade do verso, mas por campos de força visuais e sonoros que desafiam a leitura convencional. Resultantes de um processo iniciado pelo poeta ainda nos anos 1950, essas obras apresentam uma estrutura verbivocovisual, característica do Concretismo, na qual palavra, som, cor e forma se articulam de maneira indissociável. Ao mesmo tempo, incorporam recursos gráficos e digitais próprios do século XXI. Para além do amplo campo tecnológico oferecido pela computação gráfica, utilizada pelo artista desde o início dos anos 1990, Augusto de Campos também experimenta com elementos pontuais de seu contexto, com a ideogramática e a lógica matemática, além de procedimentos de intertextualidade que dialogam com referências como Marcel Duchamp, James Joyce e Fernando Pessoa, entre outros, bem como com estratégias associadas ao conceito de “ready-made”.

Nas obras Esquecer (2017) e Vertade (2021), a leitura deixa de ser linear e torna-se também perceptiva, quase física, exigindo do leitor um acompanhamento atento. Em Vertade, Augusto de Campos engana o olhar por meio da troca das letras D e T nas palavras antônimas verdade e mentira, instaurando um curto-circuito semântico que tensiona a confiança na leitura. Já em Esquecer, o artista promove a perda progressiva das palavras a partir de um poema preexistente, resgatado e inserido sobre a superfície de um céu nublado. À medida que atravessam as nuvens, os vocábulos se esmaecem e se confundem com a imagem, provocando um efeito de apagamento visual que se converte em reflexão sensível sobre memória, esquecimento e tempo. Este último, aliás, é também referência central do título da mostra, pós poemas, em que o termo “pós” carrega uma duplicidade semântica: indica tanto o depois quanto o plural de pó, matéria residual do que foi.

Serviço

Exposição | pós poemas

De 5 de fevereiro a 7 de março

Segunda, das 10 às 18h, terça a sexta, das 10 às 19h, sábado, das 11 às 17h

Período

Detalhes

A Galeria Alma da Rua, localizada em um dos endereços mais emblemáticos da capital paulista, o Beco do Batman, abre a mostra “Entre Ideias e Quintais” de Enrique Tadeu Alves

Detalhes

A Galeria Alma da Rua, localizada em um dos endereços mais emblemáticos da capital paulista, o Beco do Batman, abre a mostra “Entre Ideias e Quintais” de Enrique Tadeu Alves Ribeiro, mais conhecido como Rocket. Trata-se de uma exposição que traz dezenas de telas inéditas produzidas a partir da percepção do artista acerca de suas memórias afetivas e de sua vivência cotidiana.

As obras surgem como imagens vivas e recorrentes, que buscam traduzir sentimentos e experiências presentes em cada cena retratada. Dos botecos às ruas movimentadas em dia de jogo no campo da favela, passando pelo banho de tanque das crianças no quintal, como retrata a obra ‘Capitães’ na qual “crianças sozinhas se tornam capitães das brincadeiras”, explica o artista, cada trabalho revela fragmentos de uma memória coletiva marcada pela simplicidade, pela convivência e pela identidade do território.

Serviço

Exposição | Entre Ideias e Quintais

De 22 de fevereiro a 19 de março

Todos os dias das 10h às 18h

Período

Local

Galeria Alma da Rua II

Rua Medeiros de Albuquerque, 188 – Beco do Batman, Vila Madalena, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

O Museu de Arte do Espírito Santo (MAES) recebe a exposição Greve Negra Já!, projeto do artista Luciano Feijão, em articulação com o Movimento Grevista Negro. A mostra apresenta uma

Detalhes

O Museu de Arte do Espírito Santo (MAES) recebe a exposição Greve Negra Já!, projeto do artista Luciano Feijão, em articulação com o Movimento Grevista Negro. A mostra apresenta uma investigação estética e proposição política que contesta os modos históricos de construção do corpo negro, questionando paradigmas científicos, anatômicos e normativos que sustentaram, e ainda sustentam, estruturas de dominação racial.

A exposição parte da problematização sobre os processos de subjetividades negras que foram sistematicamente moldados pela exploração do trabalho, pela lógica capitalista de produção de valor e pela violência institucional. Nesse sentido, as obras constroem uma arena crítica que evidencia como essas engrenagens operam na manutenção de desigualdades e na naturalização da precarização da vida negra.

Reunindo desenhos e instalações, Greve Negra Já! tem curadoria de Renato Lopes (SP) e apresenta um conjunto de trabalhos que tensiona modelos hegemônicos de representação, contrapondo com outras formas de leitura do corpo, da existência e da experiência negra. As obras atuam como dispositivos de confronto, instaurando uma perspectiva que recusa padrões impostos e afirma a possibilidade de reorganização política.

A noção de greve, no contexto da exposição, é construída enquanto campo de atuação amplificados e peça-chave para pensarmos mudanças radicais. Mais do que suspensão, trata-se de um posicionamento ativo, um movimento estratégico de anulação das lógicas que transformam a exploração da população negra em norma. A mostra evidencia a centralidade da classe trabalhadora negra na produção de riqueza, ao mesmo tempo em que denuncia sua exclusão sistemática do acesso a essa riqueza.

Ao estabelecer um diálogo direto com os legados da escravização e suas atualizações contemporâneas, Greve Negra Já! se afirma como uma ação direta de afirmação coletiva. Com produção de Elaine Pinheiro, a exposição propõe ao público uma reflexão crítica sobre os vários mecanismos que condicionam a exploração do trabalho estritamente negro e convoca para a construção de uma consciência de classe orientada por uma perspectiva afrocentrada.

Programa educativo

Ao longo da exposição serão realizadas ações educativas para o público espontâneo. Estão previstas oficinas de desenho e uma formação específica para professores do ensino formal e não-formal, conduzida por Karenn Amorim, arte-educadora, graduada em Artes Plásticas e mestre em Artes pela Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, atualmente doutoranda em Artes pelo Programa de Pós-graduação em Artes pela Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro.

Serviço

Exposição | Greve Negra Já!

De 24 de fevereiro a 26 de abril

Terça a sexta, das 10h às 18h; sábados, domingos e feriados, das 10h às 16h

Período

Local

Museu de Arte do Espírito Santo (Maes)

Av. Jerônimo Monteiro, 631, Centro, Vitória - ES

Detalhes

Parte de um acervo de arte particular ficará disponível para o grande público entre os dias 24 de fevereiro a 26 de abril no Museu de Arte do Espírito Santo

Detalhes

Parte de um acervo de arte particular ficará disponível para o grande público entre os dias 24 de fevereiro a 26 de abril no Museu de Arte do Espírito Santo Dionísio Del Santo (MAES). É a mostra “Arte em todos os sentidos”, que vai reunir obras contemporâneas de 36 artistas capixabas e nacionais.

A mostra integra o projeto Acervo RDA – Preservação e Difusão do Acervo Ronaldo Domingues de Almeida na Midiateca Capixaba, cujo objetivo é contribuir para a democratização do acesso à arte e salvaguardar a memória do patrimônio artístico capixaba, em especial.

O projeto foi aprovado no Edital nº 18, lançado pela Secretaria da Cultura (Secultes) em 2024, e foi contemplado com recursos do Fundo de Cultura do Estado do Espirito Santo (Funcultura) e da Política Nacional Aldir Blanc (PNAB), do Ministério da Cultura (MINC).

41 obras

Com um olhar direcionado à contemporaneidade, o diretor do MAES, Nicolas Soares, fez a curadoria da exposição e selecionou 41 pinturas, gravuras, desenhos, fotografias e esculturas entre as obras que integram o acervo do colecionador de arte Ronaldo Domingues de Almeida.

“Nunca planejei formar um acervo. Queria apenas conviver com a arte no cotidiano. A coleção cresceu de forma espontânea, movida pelo interesse estético e pela experiência proporcionada por cada obra. Com o tempo, fiquei me perguntando qual o sentido de manter tantas obras restritas a poucos”, descreve o colecionador e curador adjunto da mostra.

A exposição permitirá que os visitantes apreciem criações de artistas nacionais que nunca ou raríssimas vezes expuseram em Vitória.

“Quanto aos artistas capixabas escolhidos, na impossibilidade de apresentar a totalidade, o curador selecionou nomes representativos de períodos diversos, buscando obras cujas temáticas fogem daquelas pelas quais habitualmente são reconhecidos”, completa a jornalista Adriana Machado, coordenadora do projeto e produtora executiva da exposição.

O nome “Arte em todos os sentidos” é uma referência a um detalhe de uma obra do artista Paulo Bruscky, uma arte postal, cujo título é “Hoje a Arte é este Comunicado”. A peça faz parte do acervo e a escolha do título dialoga com o projeto.

Projeto Acervo RDA

A mostra é uma das ações formativas integradas ao projeto Acervo RDA, que está em execução. Obras do acervo estão sendo catalogadas e digitalizadas para inserção na plataforma online do Governo do Estado, Midiateca Capixaba.

A realização da exposição no MAES se deve ao convite feito pela instituição, por reconhecer a relevância do projeto tanto em relação à preservação da memória dessas obras quanto pelo propósito de buscar a democratização do acesso à arte.

“Foi dessa reflexão que nasceu o desejo de compartilhar. A digitalização e a inserção do acervo na Midiateca Capixaba transformam o que era privado em acesso público, ampliando a experiência da arte e sua função social. E, agora, estamos levando parte desse acervo fisicamente durante a exposição”, acrescenta Adriana Machado.

Serviço

Exposição | Arte em todos os sentidos

De 24 de Fevereiro a 26 de abril

Terça a sexta, das 10h às 18h; sábados, domingos e feriados, das 10h às 16h

Período

Local

Museu de Arte do Espírito Santo Dionísio Del Santo (MAES)

Avenida Jerônimo Monteiro, 631, Centro de Vitória - ES

Detalhes

A Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel tem o prazer de apresentar Purple apple, primeira exposição individual de Willa Wasserman no Brasil, na FDAG Jardins, em São Paulo.

Detalhes

A Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel tem o prazer de apresentar Purple apple, primeira exposição individual de Willa Wasserman no Brasil, na FDAG Jardins, em São Paulo. A mostra reúne pinturas íntimas, de pequena escala, sobre linho e latão, ao lado de obras de grandes dimensões sobre tecido, produzidas entre Nova York, onde a artista vive, e São Paulo, onde atualmente realiza uma residência na Casa Onze.

Wasserman investiga questões de intimidade, gênero e metamorfose, entrelaçando referências à pintura clássica e à cultura material com expressões contemporâneas da experiência queer. Trabalhando sobre tecidos e metais, a artista trata o suporte como participante ativo de cada composição. Óleo, silverpoint — traços obtidos pelo atrito da prata sobre uma superfície preparada — e processos químicos são aplicados de modo a permitir que oxidações, manchas e variações tonais emerjam e permaneçam visíveis. Sua abordagem da figuração evita a nitidez corporal ou contornos rigidamente definidos, privilegiando espaços amorfos onde formas flutuam e se dissolvem. Técnicas históricas são reimaginadas para dar origem a corpos e atmosferas mutáveis, ao mesmo tempo luminosos e sombrios, suspensos em um estado de emergência contínua.

Há tempos, Wasserman trabalha a natureza-morta como um modo de pensar visualmente, tratando os objetos como uma composição silenciosa, mais do que como uma exibição simbólica. Ela pinta arranjos florais e cenas de jardim, como em From the garden at the new squat (2026) [Do jardim da nova ocupação], em que o pigmento parece fundir-se à superfície metálica, conferindo às imagens uma profundidade quieta e ambiente. Em Still life with purple apple, empty bowl, lock rake (2026) [Natureza-morta com maçã roxa, tigela vazia, instrumento para destravar fechaduras], o instrumento introduz uma nota de acesso transgressivo, fazendo referência a experiências vividas da identidade trans e a modos de atravessar espaços para além de estruturas normativas.

Serviço

Exposição | Willa Wasserman: Purple apple

De 25 de fevereiro a 18 de abril

Terça a sexta, das 10h às 19h, sábado, das 10h às 18h

Período

Local

Galpão Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel Jardins

Rua Barão de Capanema 343, Jardins – São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

O Sesc Sorocaba recebe a 4ª edição de Frestas – Trienal de Artes. Intitulada do caminho um rezo, a mostra expõe o ato de caminhar como gesto político, espiritual e de

Detalhes

O Sesc Sorocaba recebe a 4ª edição de Frestas – Trienal de Artes. Intitulada do caminho um rezo, a mostra expõe o ato de caminhar como gesto político, espiritual e de construção de conhecimento, aproximando práticas artísticas, educativas e comunitárias.

Com a curadoria de Luciara Ribeiro, Naine Terena e Khadyg Fares, a Trienal propõe uma escuta atenta ao território sorocabano, atravessando suas camadas históricas, visuais e sociais.

O título do caminho um rezo une o conceito de “caminho como rezo”, difundido pelo professor e artista Tadeu Kaingang, à noção andina de “Thaki”, descrita pela socióloga Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, e à ideia de “confluências afropindorâmicas”, do pensador quilombola Antônio Bispo dos Santos (Nêgo Bispo), orientando uma reconexão com experiências culturais, educacionais e de memória que articulam corpo, território e vida social.

São, ao todo, 188 obras (das quais 26 foram comissionadas) desenvolvidas a partir de experiências negras, indígenas, periféricas e dissidentes, que ocupam tanto a unidade, quanto espaços da cidade, como a Capela João de Camargo, o Clube 28 de Setembro, o Monumento Pelourinho e o Monumento à Mãe Preta.

Assim como nas edições anteriores, Frestas se afirma como uma iniciativa que descentraliza o circuito de arte contemporânea, reconhecendo Sorocaba e o interior paulista como território de confluência entre relações artísticas e comunitárias.

Serviço

Exposição | do caminho um rezo

De 27 de fevereiro a 16 de agosto

Terças a sextas, 9h às 21h30. Sábados, 10h às 20h. Domingos e feriados, 10h às 18h30. Exceto dia 3/4

Período

Local

Sesc Sorocaba

R. Barão de Piratininga, 555 - Jardim Faculdade, Sorocaba - SP

Detalhes

Paisagens com horizontes e formações aparentemente vegetais, possivelmente geológicas. Cenas internas e externas, de interações humanas e animais. Telas veladas por chassis e caixas, cenas reveladas entre molduras teatrais —

Detalhes

Paisagens com horizontes e formações aparentemente vegetais, possivelmente geológicas. Cenas internas e externas, de interações humanas e animais. Telas veladas por chassis e caixas, cenas reveladas entre molduras teatrais — esses são alguns dos principais motivos que aparecem na produção recente de Thales Pomb. Suas pinturas, desenhos e esculturas produzem imagens que não podem ser facilmente associadas à realidade. Ao confrontar a tensão entre cor e forma na constituição pictórica, essas obras subvertem a figuração para favorecer o gesto. As figuras, cenas e paisagens se tornam aqui, meios metafísicos para a contemplação do imaginar.

Montando e desmontando liminarmente o espaço-tempo, os campos de cores difusas nas pinturas evocam luzes raras, como a luminosidade oblíqua que envolve o entorno do nascer e do pôr do sol, especialmente na natureza. Essas luzes atravessam o espaço em pouco tempo e apesar — ou por causa — disso, depositam momentos de suspensão, em que tudo está por ser revelado ou ocultado, tudo parece prestes a se transformar. Os contrastes e gradações cromáticas esquematizam fases de uma luz fragmentada, estruturando o espaço-tempo de um gerúndio perpétuo, em que há apenas o possível infinito do momento enquanto ele se torna.

Nas pinturas recentes de Thales Pomb, cenas são frequentemente constituídas em séries, como a série de montadores, a série de gatos ao ar livre e a série de bocas de cena. Na primeira, as imagens mobilizam montadores de obras de arte entre formas e espaços liminares, remetendo às dinâmicas misteriosas do próprio mundo da arte: a circulação de obras, sua entrada e saída controlada dos espaços. O conteúdo dessas obras é um dado velado, mas indiferente — os chassis, as caixas e as embalagens integram-se ao ritmo dos campos de cor matizados entre luz e sombra, das horizontais e diagonais que sugerem possíveis horizontes e profundidades, estruturando tempo e espaço. Os movimentos das caixas e dessas obras veladas não geram suspeitas sob a luz solar: atravessam naturalmente os planos por onde essa luz se espreguiça, como se estivesse chegando ou se preparando para se retirar. Os títulos dessas pinturas aludem à dança e à coreografia de movimentos precisos: bailando, tango, passinho, ajustezinho, bolero e puxadinha. O potencial de desprendimento dessas ações está contido na tensão entre cores e formas, que, ao depositar metafisicamente o tempo no espaço pictórico, utiliza a figuração para gesticular a poética de uma incógnita.

Se na pintura sobre tela Thales Pomb trabalha a partir da “queima”, aplicando sobre a tela camadas intensas de tons quentes das quais emerge a imanência formal de suas imagens, nos desenhos em lápis Conté sobre papel Ingres o artista estabelece outra imanência, fundada no branco do papel — o “fundo” material dessas imagens. As manchas e marcas em tons de cinza e preto produzidas pelo Conté reverenciam os efeitos de luz e sombra dos desenhos de Georges Seurat (1859–1891), valendo-se também da textura do papel Ingres para sugerir massas à contraluz. Nesses desenhos, a densidade das formas mais escuras relaciona-se com campos vazios — ou suavemente constituídos —, produzindo o mesmo efeito suspensivo presente nas pinturas.

A produção recente de Thales Pomb, ao criar imagens a partir da cor e da forma, propõe uma reflexão sobre a dificuldade contemporânea de “estar presente”: contemplar o momento exige a capacidade de habitar o inquietante. Isso não significa sucumbir à hiperestimulação sensorial, mas buscar aquilo que ainda não se conforma à imagem do real. Refletindo sobre a filosofia prática de nosso tempo, Vladimir Safatle propõe que, diante do agravamento das crises e da urgência de nos confrontarmos com o real, seria preciso “deixar os fragmentos da experiência falarem, serem expostos no ponto inicial em que colidem com o pensamento”. Safatle sugere que o sublime, como outros conceitos, está submetido à obsessão contemporânea por segurança, motivo da intolerância geral à colisão e à ruptura. O sublime, porém, “enquanto conceito indeterminado da razão”, liga-se às experiências que fazem a imaginação confrontar seus próprios limites, formalizando justamente “o que não se submete à forma da representação”. Se historicamente o sublime esteve na sensação de pequenez ou de terror diante da totalidade imposta pela natureza, na contemporaneidade o sublime está justamente na sensação de fragmentação que um mundo em crise produz.

Essa fragmentação se reflete na pintura de Thales Pomb, em que cada campo de cor pode ser visto individualmente ou separadamente, fazendo e desfazendo a unicidade da imagem. Thales refletiu em seu ateliê: “Antes, eu já sabia a imagem que queria desde o começo. Agora, eu não sei o que vou pintar. Eu pago para ver”. No lugar de uma dependência projetual que assegura a imagem antes mesmo de existir, suas pinturas e desenhos enfrentam a experiência espaço-temporal do momento, sem a pretensão de conhecê-lo como definição. Apenas com a consciência de que o gesto pictórico é capaz de dar forma à liminaridade sublime e transformar cada instante em um momento de contemplação.

Gabriela Gotoda – curadora

Serviço

Exposição | Enquanto se torna

De 28 de fevereiro a 13 de abril

Segunda a sexta-feira, das 10hs às 19hs; sábado, das 10hs às 15hs

Período

Local

Danielian Galeria SP

R. Estados Unidos, 2114 - Jardim Paulista

Detalhes

A escultora e artista visual Mylene Costa realiza sua primeira exposição individual no Brasil com a mostra Forma e Permanência, no Espaço Heróis de 32, na Assembleia Legislativa de São Paulo. A exposição

Detalhes

A escultora e artista visual Mylene Costa realiza sua primeira exposição individual no Brasil com a mostra Forma e Permanência, no Espaço Heróis de 32, na Assembleia Legislativa de São Paulo. A exposição reúne dez esculturas, incluindo trabalhos inéditos, que investigam o silêncio, a permanência e a feminilidade como estrutura da forma. Com curadoria de Paco de Assis, a mostra propõe ao visitante uma experiência marcada por densidade, gravidade e presença.

Na prática artística de Mylene Costa, a forma precede o discurso. A matéria não ilustra um tema – ela sustenta uma experiência de percepção direta, marcada por contenção, densidade e tensão interna.

Trabalhando com bronze, resina e mármore, a artista investiga a forma como presença e pensamento: o silêncio como estrutura, o tempo como permanência e o corpo como matriz da linguagem.

A feminilidade também atravessa sua poética, não como tema ilustrativo, mas como princípio estrutural de forma e tensão, que organiza a matéria, combinando resistência, fluidez e tensão. Cada obra propõe ao espectador uma relação íntima como o corpo, o tempo e o espaço.

Um dos destaques da mostra “Forma e Permanência”, em cartaz na Assembleia Legislativa de São Paulo, é a série “Nebra”, que reforça a ideia de silêncio como força ativa e de permanência como linguagem escultórica, sem recorrer a gestos explícitos ou a movimentos coreográficos, mas por se tratarem de esculturas com gesto, movimento interno, peso, compressão e gravidade.

“Na exposição, o silêncio não aparece como ausência, mas como um espaço ativo que intensifica a presença da obra. O tempo é tratado como permanência e ao privilegiar o silêncio, pausa e densidade, eu proponho ao visitante um contraponto à aceleração do nosso cotidiano e reafirmo a experiência física do corpo e da matéria”, comenta a artista.

Realizada em março, mês dedicado às mulheres, a exposição também amplia o debate sobre a presença feminina na construção simbólica do espaço público-institucional. Segundo o curador Paco de Assis:

“A feminilidade aqui não é adorno nem discurso. É estrutura. Como dobras e fendas que organizam a matéria sem fazê-la ceder, o feminino se manifesta como inteligência da flexibilidade: capacidade de acolher tensão, mudar de direção e, ainda assim, permanecer”.

Serviço

Exposição | Forma e Permanência

De 3 a 13 março

Segunda a sexta, das 8h30 às 18h. Fechado aos sábados e domingos

Período

Local

Assembleia Legislativa de São Paulo - Espaço Heróis de 32

Av. Pedro Álvares Cabral, nº 201, Ibirapuera, São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

A CAIXA Cultural São Paulo apresenta a exposição Solidão Coletiva, individual inédita de Julio Bittencourt que propõe uma reflexão visual sobre as contradições da sociedade contemporânea e os modos de

Detalhes

A CAIXA Cultural São Paulo apresenta a exposição Solidão Coletiva, individual inédita de Julio Bittencourt que propõe uma reflexão visual sobre as contradições da sociedade contemporânea e os modos de existência em um mundo cada vez mais povoado, acelerado e regulado. Com curadoria de Guilherme Wisnik e expografia assinada por Daniela Thomas, a mostra reúne oito séries fotográficas realizadas entre 2016 e 2023, resultado de um extenso trabalho de observação em grandes centros urbanos como São Paulo, Nova York, Tóquio, Mumbai, Pequim e Jacarta.

O título da exposição dialoga com o pensamento da filósofa Hannah Arendt, para quem a sociedade moderna, estruturada em torno do trabalho, tende a suprimir a possibilidade de ação e a reduzir o indivíduo à condição de agente funcional. “As imagens de Bittencourt observam grupos humanos imersos em rotinas produtivas, fluxos incessantes de informação e espaços que impõem contenção física e simbólica. O confinamento surge como eixo recorrente, mesmo quando os mecanismos de controle não se apresentam de forma explícita”, conta Wisnik.

Em suas fotografias, Julio Bittencourt busca registrar não acontecimentos extraordinários, mas estados de suspensão. São, para o artista, corpos anônimos, captados em situações de espera, repetição ou adaptação a ambientes que os condicionam. De empregados isolados em escritórios a trabalhadores alojados em hotéis cápsula, a privação deixa de ser exceção para se tornar parte estrutural do cotidiano urbano. “Há, nesse gesto, uma dimensão política que não se baseia na denúncia direta, mas na insistência em tornar visível aquilo que costuma passar despercebido”, diz o curador.

As séries se articulam como capítulos de uma narrativa aberta, marcada por tensão e ressonância. Transitando entre o documental e o conceitual, Julio Bittencourt explora a fotografia como linguagem crítica, livre do compromisso jornalístico com o fato imediato, mas atenta às possibilidades poéticas do olhar.

Solidão Coletiva – Júlio Bittencourt é uma exposição apresentada pela CAIXA Cultural, com realização da Phi Projetos e Cinnamon e patrocínio da CAIXA e Governo do Brasil.

Serviço

Exposição | Solidão Coletiva

De 03 de março a 12 de julho

Terça a domingo, das 9h às 18h

Período

Local

CAIXA Cultural São Paulo

Praça da Sé, 111 – Centro – SP

Detalhes

O CCBB BH recebe a exposição “Marlene Barros: Tecitura do Feminino”, com obras em escultura, crochê e bordado da artista maranhense Marlene Barros, propondo uma reflexão sobre o corpo feminino, a desvalorização histórica

Detalhes

O CCBB BH recebe a exposição “Marlene Barros: Tecitura do Feminino”, com obras em escultura, crochê e bordado da artista maranhense Marlene Barros, propondo uma reflexão sobre o corpo feminino, a desvalorização histórica das mulheres e a invisibilização de seus fazeres no campo da arte. Com curadoria de Betânia Pinheiro, a mostra transforma o gesto íntimo do costurar em narrativa pública de resistência, pertencimento e reinvenção, transformando agulha e linha em instrumentos de denúncia, memória e elaboração simbólica.

A exposição conta com instalações como “Eu tenho a tua cara”, com 49 rostos de mulheres que trocam olhos e bocas costurados, tensionando identidade e alteridade; “Caixa Preta”, que constrói um autorretrato expandido a partir de fotografias, intervenções têxteis e escritos; “Coso porque está roto”, que apresenta um casaco cujo avesso revela órgãos bordados que simbolizam sentimentos e acionam a ideia de reparo; “Entre nós”, que mergulha em objetos de crochê para problematizar tarefas naturalizadas no âmbito doméstico; e “Quem pariu, que embale”, que questiona a atribuição quase exclusiva do cuidado dos filhos às mulheres. A montagem do percurso expositivo, coordenada por Fábio Nunes, com produção executiva de Júlia Martins, propõe uma trajetória não cronológica, permitindo que o público construa sua própria experiência entre matéria, gesto e memória.

Com mais de quatro décadas de atuação, Marlene Barros consolidou-se como referência no cenário artístico maranhense, articulando produção, formação e redes culturais por meio do Ateliê Marlene Barros e do Ponto de Cultura Coletivo ZBM. A exposição tem origem em pesquisa desenvolvida durante seu mestrado em Arte Contemporânea na Universidade de Aveiro, quando propôs costurar simbolicamente uma casa em ruínas no campus Santiago, em Portugal, em um gesto de remendar fissuras do tempo. A casa, convertida em metáfora do corpo, permitiu expandir a reflexão para o universo feminino em suas dimensões sociais, políticas e afetivas, compreendendo a tecelagem como metáfora dos vínculos, da memória e do fluxo da vida.

Serviço

Exposição | Marlene Barros: Tecitura do Feminino

De 04 de março a 01 de junho

Quarta a segunda, das 10h às 22h

Período

Local

Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil Belo Horizonte (CCBB BH)

Praça da Liberdade, 450 - Funcionários, Belo Horizonte - MG

Detalhes

A exposição Rafael Pereira: A Cabeça de Zumbi inaugura a programação de 2026 da Galeria Estação, reafirmando a força poética e a crescente complexidade do trabalho do artista paulistano de

Detalhes

A exposição Rafael Pereira: A Cabeça de Zumbi inaugura a programação de 2026 da Galeria Estação, reafirmando a força poética e a crescente complexidade do trabalho do artista paulistano de 39 anos. Ao longo de sua trajetória Rafael percorreu diversos Estados do Brasil, viveu por 14 anos decisivos em Teófilo Otoni (MG) e, atualmente, reside em Caraguatatuba, no litoral norte de São Paulo.

Desde Lapidar Imagens, sua primeira exposição individual na galeria, realizada em 2023, o artista atravessou um ciclo de amadurecimento que ampliou seu vocabulário visual ao revisitar aspectos estruturantes de sua trajetória — da formação como lapidador de pedras preciosas às experiências de circulação pelo país. Esse percurso se desdobra agora em uma mostra que articula memória, identidade e subjetividade.

“Desde que Rafael entrou na Estação, em 2023, acompanhamos de perto seu processo consistente de amadurecimento. Ele é um artista que cresceu em segurança, em repertório e em consciência do próprio trabalho. Entre Lapidar Imagens e esta nova individual sua obra ganhou densidade. A exposição reflete um salto real em sua trajetória. Quando um artista como ele encontra um espaço institucional que o apoia, ele ganha o mundo. No caso dele, nosso respaldo foi fundamental para que ele se sentisse mais livre para arriscar, aprofundar processos e ampliar sua linguagem”, defende Vilma Eid, sócia-fundadora da Galeria Estação.

Produzidas no biênio 2024 – 2025, as pinturas inéditas incorporam um universo multicolorido de retratos, paisagens e elementos simbólicos que, segundo o artista, emergem de uma escuta profunda de si mesmo, em um processo consciente de desaceleração: “Hoje eu sinto que o meu trabalho acontece em outro tempo. Antes, eu tinha muita urgência, uma necessidade de produzir o tempo todo, quase como se eu precisasse provar alguma coisa. Agora eu entendo que esses processos devem ser mais lentos, que a pintura precisa de tempo para maturar, assim como eu”, explica.

Composta por dois núcleos expositivos, a mostra reúne 22 pinturas no 2º andar da Galeria Estação — sendo 20 retratos e duas naturezas-mortas — e apresenta, no mezanino, a série Nbimda, formada por 16 pinturas de cabeças de dimensões variáveis. Cada obra representa uma divindade (nkisi) cultuada no candomblé de Angola de matriz Bantu. Ao abordar esse conjunto, o historiador da arte Renato Menezes, autor do texto crítico do catálogo da mostra, destaca a centralidade simbólica da cabeça como elo entre o corpo, a ancestralidade e o divino:

“O que para os europeus se apresentou unicamente como fisionomia, isto é, como emanação da personalidade, revela-se, na pintura de Pereira, como elo com o divino: a cabeça, orí para os Iorubá e mutuê para os Bantu. É na cabeça onde reside a força vital do indivíduo; está ali sua conexão com o nkisi, a energia ancestral e destino individual que cada sujeito traz consigo ao nascer. O tema da cabeça ancestral organiza a série Nbimda”, destaca Menezes.

Ao exaltar e ressignificar a ancestralidade afrodiaspórica que constitui parte majoritária da sociedade e da formação cultural brasileira, Rafael também explicita sua intenção de dar maior complexidade às discussões sobre racialidade, afastando-se de leituras reducionistas em favor da construção de uma subjetividade negra.

“Não quero que meu trabalho seja lido só a partir de um corte racial. Não quero que um corpo negro sorrindo seja visto como um acontecimento, enquanto um corpo branco sorrindo é só uma imagem. O que me interessa é construir uma subjetividade negra que seja complexa, íntima e contraditória. Não quero negar a questão racial. Quero ir além dela. Quero que meu trabalho seja visto como imagem e experiência, e que a negritude esteja ali de forma profunda, não como um rótulo”, provoca o artista.

Segundo Menezes, essa produção recente, marcada pela força intuitiva do gesto pictórico, amplia ainda mais as leituras possíveis sobre a obra de Rafael, já insinuadas na interpretação de caráter modernista dos trabalhos presentes em Lapidar Imagens.

“Em um primeiro momento, sua obra parece resultar diretamente da absorção desses códigos da retratística tradicional para, a partir deles, imaginar futuros, reconstituir histórias e inventar identidades, superando o modo como a vida negra foi avaliada. Por outro lado, o artista cria fisionomias a partir de sua imaginação, como em um exercício de ajuste de contas com a história e de acesso a uma dimensão da memória neutralizada pelo trauma: a intuição é uma tecnologia ancestral. Assim, ele faz reexistir, por meio de suas cores, a presença viva de pessoas atravessadas por sentimentos, pensamentos e desejos silenciosos”, observa Menezes no catálogo.

A exposição evidencia, ainda, a ampliação de técnicas experimentadas durante o período formativo de Pereira, como o uso de bastão de giz pastel óleo sobre papel, revelando processos investigativos de um trabalho em transformação. Parte das obras foi produzida em março de 2025, durante a residência artística realizada por ele em Goiânia (GO), no Sertão Negro Ateliê e Escola de Artes, projeto idealizado pelo artista visual e educador Dalton Paula e pela professora e pesquisadora de cinema Ceiça Ferreira. Localizado em um quilombo do bairro conhecido como Setor Shangri-lá, o espaço articula tradições culturais afro-brasileiras e práticas de arte contemporânea, com atividades em cerâmica, gravura, capoeira angola, agroecologia e cineclube.

“A residência no Sertão Negro foi decisiva para o Rafael, não apenas no plano técnico, mas como experiência de troca com outros artistas e abertura de mundo. Ele voltou mais seguro, mais consciente da própria voz — e isso aparece com força nesta exposição, que mostra um Rafael mais amplo com trabalhos diferentes reunidos em dois núcleos distintos. São quase duas exposições que se complementam e ajudam a entender melhor o artista. Abrir a programação de 2026 com o Rafael foi uma decisão muito consciente. Ele tem um público forte, seu trabalho tem ótima circulação e esse é o momento exato para fazermos sua segunda individual”, conclui Vilma Eid.

Serviço

Exposição | A Cabeça de Zumbi

De 5 de março a 11 de abril

Segunda a sexta, das 11h às 19h; sábados, das 11h às 15h; não abre aos domingos

Período

Local

Galeria Estação

Rua Ferreira de Araújo, 625 - São Paulo - SP

Detalhes

O MASP — Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand exibe Claudia Alarcón & Silät: viver tecendo. A mostra reúne 25 trabalhos que contemplam a produção artística de Claudia

Detalhes