In the midst of a pandemic and political crisis context, what are the curatorial and exhibition possibilities? This was one of the questions that guided months of work in The river is a serpent, third edition of Frestas – Art Triennial. Organized by Sesc São Paulo, based at its Sorocaba unit, it is curated by Beatriz Lemos, Diane Lima and Thiago de Paula Souza.

The invitation to the trio came before the pandemic, enabling the first activities in the construction of the project. On a trip across Brazil, the curators visited locations in the North and Northeast: “The most important thing for us was to create a curatorial body from this moving body in conflict with other territories”, explains Beatriz. It was in this movement that The river is a serpent began to take shape, not as a theme – which would be insufficient for the current moment -, but as a cosmovision that brings together the learnings of its process and aims to discuss the contemporaries movements, their geographies and colonial structures.

But how does Frestas ended up happening in Sorocaba? From a sequence of listening meetings with local artists, producers, managers and educators, the team sought to understand the region’s needs and made education one of the central axes of curatorial thinking. “It has always been a great concern for us not to be like a spaceship that lands in the city ‘bringing knowledge’ and then leaving”, explains Renata Sampaio, educational coordinator. If the general context seemed so vertical, the proposal here was to change this dynamic. “We didn’t want to reproduce the colonial vision of those who just want to teach and not build together”, she adds.

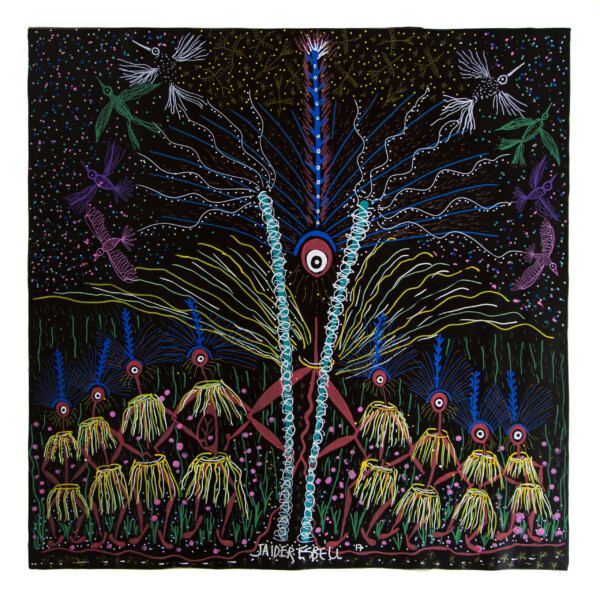

With the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic, the entire art world saw the need to rethink their programming. With the triennial it was no different. The exhibition was postponed several times and is currently scheduled for August 2021. For the curators, this decision brings up a discussion about their professional functions: “perhaps the curatorial practice is not limited to an exhibition organization”, explains Thiago de Paula. With that in mind, they changed the direction of the project and decided to focus even more on educational practices. If “the river is a serpent because it hides and camouflages, and between the unpredictable and the mystery it creates strategies for its own movement”, as the curatorial text summarizes, it is with a focus on the course and curves of this river – and on the dialogues that these promote – that Frestas decides to build itself. “This image has helped us to think about this cosmovision and has enabled us to find strategies and possibilities to face what it means to cure an exhibition of contemporary art at this moment in Brazil”, explains Diane Lima.

The affluents

It was in this context that the idea of the Study Program took shape. Fifteen artists whose lives and practices are directly connected to colonial violence were invited to participate in a series of virtual meetings with the triennial’s curatorship, production and educational teams. “We had intense meetings discussing projects, poetics, practices and life”, says Thiago. In this meetings, the artists were able to elaborate their own artistic projects, which will make up the exhibition.

Based on the experiences and ideas of Castiel Vitorino Brasileiro, Davi de Jesus do Nascimento, Denilson Baniwa, Denise Alves-Rodrigues, Ella Vieira, Gê Viana, Iagor Peres, Jonas Van Holanda, Juliana dos Santos, Laís Machado, Luana Vitra, Pedro Victor Brandão, Rebeca Carapiá, Sallisa Rosa and Ventura Profana, the meetings brought focus to several of the discussions that permeated curatorial thinking. With this, not only did the artists leave video calls with new provocations, but the curators could rethink the exhibition possibilities.

The river is a serpent: topics for difference and social justice, an online teacher training program, held in weekly meetings between October and November 2020, was also taken in this direction. “The approval was so great that the training became an county official course, offering career progression to the participating teachers”, says Renata Sampaio, who led the program.

At each meeting, one or more speakers would join the group to discuss strategies for working in the classroom. “The idea was not to show the teacher how to teach, but to raise awareness about issues that we think are of paramount importance, so that the debate can continue, in a horizontal way, at school”, explains Renata. “The educational in this edition of Frestas is working from non-hegemonic perspectives, agents and concepts, seeking to build relationships with other areas of knowledge”, she adds.

Online, however, expanded Frestas’ geographic borders. In the Training Program, it enabled the participation of educators and guests from different places in Brazil and the availability of this material online so that more people could be impacted. In general terms, it allowed for an even more intense exchange with the international scene, based on the partnership established with the Ayllu collective, a group of artistic-political action and collaborative research formed by migrant, racialized and gender and sexual dissidents from the former Spanish colonies, headquartered in Madrid.

Seeking a critical space for collective thinking and creation, Ayllu developed the Program Oriented to Subaltern Practices (POPS), which brought together around 40 people from eight Latin American countries to question rationalism, scientism and the false objectivity of Eurocentric thinking. The discussions generated a collective fanzine that will be part of the show The river is a serpent and added another discussion to the project, bringing the debate to migration issues.

The participation of people from 25 of the 27 federative units in Brazil in the expography course also sets the tone for this expansion of Frestas. Conducted by Tiago Guimarães, exhibition architect of the triennial itself, the course aimed to contribute so that more people had access to information about the area. Anti-analysis, a mentoring project by Pêdra Costa, assisted 45 artists from all over Brazil when it happened online, which would not have been possible if it had tooken place in Sorocaba, as they had initially thought.

Reaching the mouth of the river

If the initial objective of The river is a serpent was to take the discussions of the Brazilian and world contemporary art circuit to Sorocaba, finding less violent paths, it seems that the educational practices not only created these points of dialogue with the city, through the Training Program , but proposed discussions at other points in the circuit. These discussions will flow into Sorocaba in the face-to-face and virtual exhibition proposed for the second half of 2021.

Along this river, not only were artists and educators able to rethink their processes and the absences and possibilities around them, but so did the Triennial team and Sesc itself. “I’m rooting for the institution to review itself in some practices, because it is still very white and this is something that needs to be thought about”, points out Thiago. The focus on the process, education as the main pillar of the project and the joint construction of knowledge seem to have been important tools for this, because, as Renata Sampaio concludes: “The path of this river was made in the meetings, and the meeting is a two way street, everyone leaves modified after it”.

Leia a reportagem em português clicando aqui.